What work do you do specifically?

I am involved in two international initiatives in bird monitoring: the second European Breeding Bird Atlas (EBBA2) and the Pan-European Common Bird Monitoring Scheme (PECBMS), both organised within the European Bird Census Council (EBCC). My position is hosted by the Czech Society for Ornithology (CSO).

The European Atlas was published as a book in December 2020, but the work is not over. We are busy with an online version, making the outputs available to research and conservation and building capacity for bird monitoring in European countries where it is needed. The latter is closely linked to the PECBMS, but setting up a representative and sustainable bird monitoring scheme is a challenge, and we need more monitoring systems, especially in southern and eastern parts of Europe.

How does your work contribute to the assessments done by the EEA?

The wild bird indicators produced by PECBMS are directly used by the EEA. Together with the population index of grassland butterflies, the population index of common birds in Europe contributes to the EEA’s set for the indicator ‘Abundance and distribution of selected species in Europe’.

The outputs of our work have been used in the State of nature in the EU report and other publications. We have been in regular contact with colleagues in the EEA and coordinate our efforts and the feedback from the EEA is extremely important. Recently, we started exploring how the atlas data (EBBA2) can contribute to the work of bodies like the EEA.

How did you get interested in this area of work?

Probably as many other ornithologists, since my childhood I have been interested in birds, nature and conservation. I studied zoology at the Charles University in Prague where I did my Master’s degree and PhD on buzzards. Then I took an opportunity to work for the CSO as a director, where I was the only paid employee at the time.

The link between scientific knowledge and policy is the main issue that keeps me interested in large-scale bird monitoring and atlas work. Working with diverse people, various methodological approaches and cultural differences make this kind of work exciting too. I also appreciate fieldwork, which, although not automatically part of the job, is the key issue that helps to understand the data and the needs of the fieldworkers and makes one happy.

How do you assess a species’ health?

The main output of our work is collecting information about the changes in the abundance of birds and their distribution. In other words, where the birds are, how many there are and how these two parameters change. It is a long process that starts with standard fieldwork following a strict methodology.

It is not possible to cover Europe with professional fieldworkers only. But ornithology takes advantage of a crowd of amateur ornithologists or birdwatchers, who know birds and are keen to follow the methodology. Thanks to them, we can get the data from all of Europe in EBBA2 and from 28 countries in PECBMS.

The fieldworkers have to survey birds at prescribed sites, which are often selected in a randomised manner in order to ensure that the sample is representative. The observer counts all birds seen or heard at their site and records other characteristics, helping better assessment of the data at specific day times and dates.

Recordings for the distribution atlas also require information about the probability of breeding. Most of the surveys are done in early morning hours, when many birds are most active in spring, but some species are surveyed in the evenings, too. Then, the fieldworkers send the data to the national coordinators, who perform data quality checks and submit the data to the European coordinators.

© Marek Mejstřík, REDISCOVER Nature /EEA

How does this monitoring help governments in taking action?

Information about bird distribution and abundance helps decision-makers to prioritise management and conservation actions. The information about population trends and changes in the distribution serves as a signal of the health of bird populations and of the wider environment.

Monitoring outputs are regularly used in an assessment of a conservation status of species, including the European Red List categorisation. Changes in abundance and distribution of groups of species, such as farmland birds, provide signals about the health of a particular habitat type or the impact of a large-scale phenomenon like climate change.

Linking the monitoring data with environmental or other variables can tell us more about forces driving the trends; it can help to shape management practices too.

How do environmental degradation and climate change impact bird life?

The changes in European landscapes and climate are sometimes dramatic and they affect bird populations. However, the impact is not uniform: some species benefit from the changes, others do not. Overall, however, it appears that there are more losers than winners.

Intensive land use is leaving less resource for birds — this is the main human pressure. This is particularly evident for farmland and birds using this type of habitat. Intensive agricultural practices, including excessive use of pesticides and fertilisers, heavy machinery or removal of fallow land, makes modern farmland less and less suitable for birds and other wildlife.

Overall, the homogenisation of agricultural fields has a negative effect on biodiversity. The farmland bird index in Europe declined by 57 % between 1980 and 2018 and the distribution range of the farmland birds as a group shrunk in the last 30 years in Europe (EBBA2). Regionally, we also see a negative effect of intensive forestry, land abandonment or intensive use of inland wetlands.

Breeding ranges are moving north. We observe a 28 km shift of the centres of the distribution range northwards on average. Although not all these changes are caused by climate change, the effect is obvious. We also detect the impact of climate change on bird populations: species with a preference for colder climates are declining and those that prefer warmer climates are increasing.

© Juerg Isler, REDISCOVER Nature /EEA

Can we still turn things around for the better?

We have documented positive trends in distribution of several protected species for which conservation measures have taken place (for instance white-tailed sea eagle or white stork). Also, in PECBMS we have shown that conservation can work, and especially Natura 2000 sites can be beneficial, also for non-target species. This suggests that conservation can reverse negative trends.

The problem is that we still don’t do enough, partly because of limited resources and partly because traditional conservation approaches (especially protected species, nature reserves) are not sufficient to help biodiversity in the wider countryside.

What can citizens or even hobby bird watchers do to help protect birds and their habitats?

Birdwatchers are key factors for a knowledge-based conservation of birds and biodiversity. They help as volunteer fieldworkers taking part in atlases and bird monitoring: in EBBA2, some 120 000 fieldworkers contributed data, 35 000 providing highly standardised survey data. In PECBMS, around 15 000 fieldworkers take part in bird counts.

We would not have had such knowledge without these skilled people — they are absolutely essential. In principle, everybody can help — even observations of single species, including those easily identified (like the white stork), can help informed decision-making. With the recent development of online portals organised within the EBCC initiative EuroBirdPortal and the development of mobile apps enhancing recording and submitting the observations, it is easier than ever before.

Many birdwatchers participating in bird monitoring schemes and atlases are also active at a local level in conservation. As they know sites where they survey birds, they often serve as guardians of the sites and initiate interventions if the sites become threatened. Their local knowledge is a big asset for conservation at the local level too.

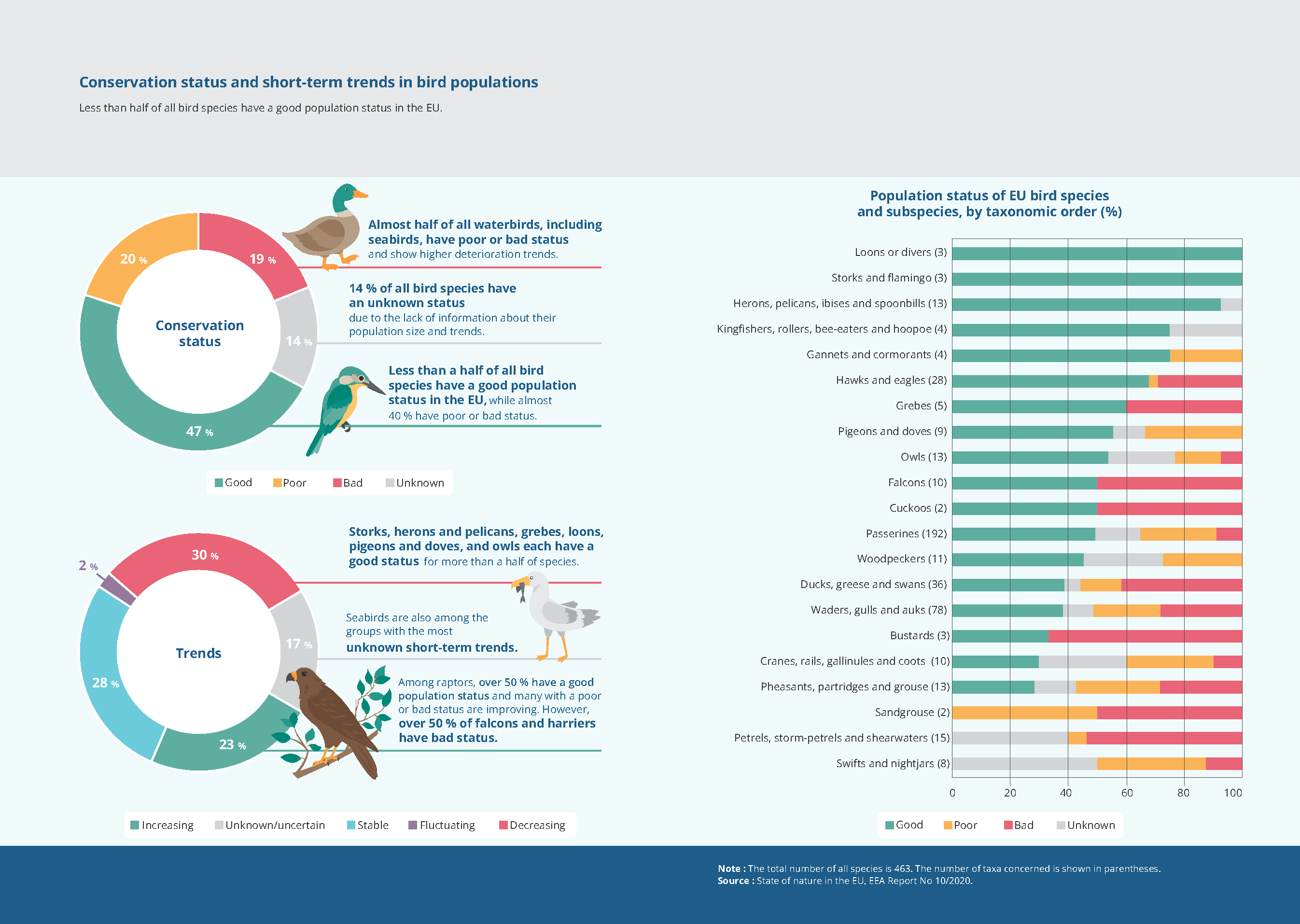

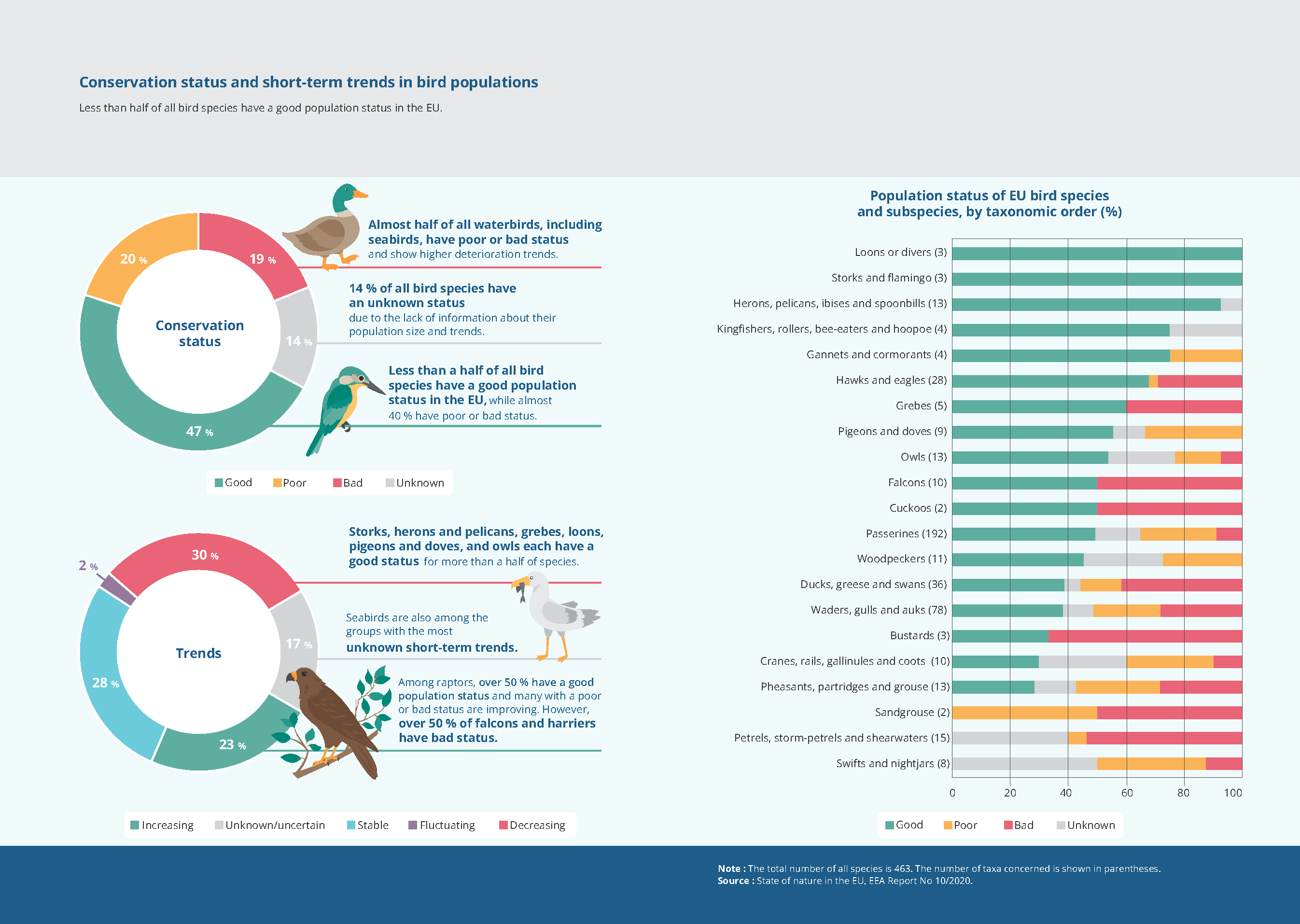

Note: The total number of all species is 463. The number of taxa concerned is shown in parentheses.

Source: State of nature in the EU, EEA Report No 10/2020.

Petr Voříšek

Member of the coordination team of the European Breeding Bird Atlas 2, Czech Society for Ornithology

Document Actions

Share with others