All official European Union website addresses are in the europa.eu domain.

See all EU institutions and bodiesBuildings are homes, work places, schools, hospitals, shops, sports halls, transport terminals, where we all spend a significant part of our day. Their construction, maintenance and demolition present many challenges and some opportunities for climate change and the environment.

Buildings and construction are closely linked to the economy, local employment and quality of life. Europe has many old cities with old buildings. Its building stock is also getting older and many old buildings are not built for efficient use of energy or a warmer climate.

Buildings must be made to protect people from the effects of climate change, including extreme heat and cold spells, both of which entail higher energy consumption for heating or cooling. Energy inefficiency, energy poverty or the poor condition of buildings often affect some groups and communities more than others.

Almost 75% of the building stock is currently energy inefficient and more than 85% of today's buildings are likely to still be in use in 2050. Energy renovation of buildings is ongoing but at a very slow rate.

The EU's renovation wave will play a key role in massively upgrading existing buildings in Europe. It will help make them more energy efficient and adapted to climate change. This will be an important element in achieving a climate-neutral EU by 2050.

Energy efficiency and climate adaptation are only part of the story. Construction and renovation require resources, demolition generates construction waste. Already around half of the world’s resource extraction is used for buildings and construction. Housing accounts for 52% of the EU’s material footprint.

Many EU countries are using recovered construction and demolition materials to a great extent but are usually downcycling waste materials. Past building practices and lack of homogenous waste materials result in waste that is not suitable for reuse or recycling. The challenge remains: our building needs to be energy-efficient — not only for heating but also for cooling; and our construction sector needs to much more circular.

Addressing the environmental and climate footprint of buildings

Construction, use and demolition of buildings causes major environment and climate pressures but smart renovations that focus on efficient use of energy and resources can help Europe increase the sustainability of its housing sector, according to a European Environment Agency report.

Ageing populations, increasing affluence and changing climate are expected to change demands for buildings’ particular uses in Europe, the EEA report notes. More buildings are likely to be needed in cities, and buildings need to contribute to environment and climate solutions, including energy saving and production, protection from climate hazards, and restoring nature.

Buildings account for

>30%

of the EU's environmental footprint

1/3

of our material

consumption

42%

of total energy consumption

35%

of greenhouse gas emissions

Cooling your home during a heatwave?

Across Europe, rising temperatures, combined with an ageing population and urbanisation, mean that the population is becoming more vulnerable to heat and that demand for cooling in buildings is rising rapidly. Buildings, as long-lasting structures, can offer protection from heatwaves and high temperatures if appropriately designed, constructed, renovated and maintained.

Our briefing examines key elements of sustainable cooling policy, and its potential impacts on vulnerable groups, by reducing health risks, inequalities and summer energy poverty.

How is Copernicus helping?

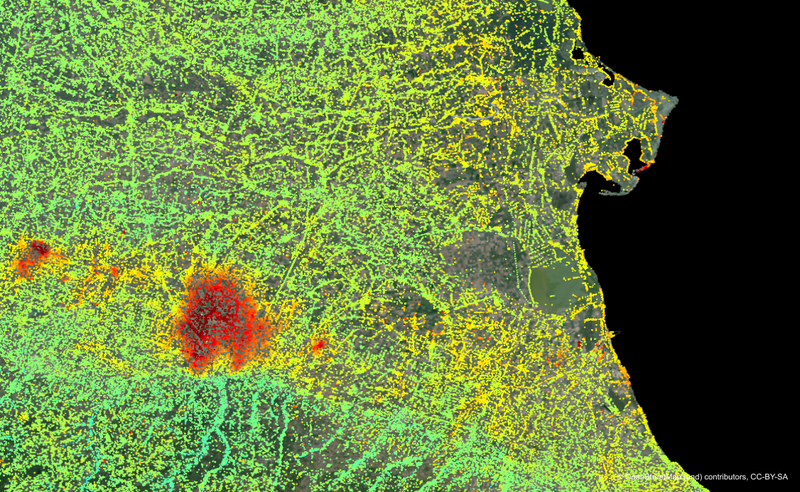

The Copernicus Land Monitoring Service offers users several products with detailed information on urban areas. High resolution imperviousness datasets reveal areas where the soil is sealed at the continental scale, including both natural and artificial surfaces. The Urban Atlas gives users access to detailed land cover and land use maps for 788 Functional Urban Areas across Europe, with additional street tree maps, building block height measurements, and population estimates.

The European Ground Motion Service product uses radar data derived from Sentinel-1 to detect and measure ground movements across Europe with milimetre precision. With this information, urban planners can make data-driven decisions about where to build new infrastructure by assessing the likelihood of natural hazards such as landslides or subsidence.

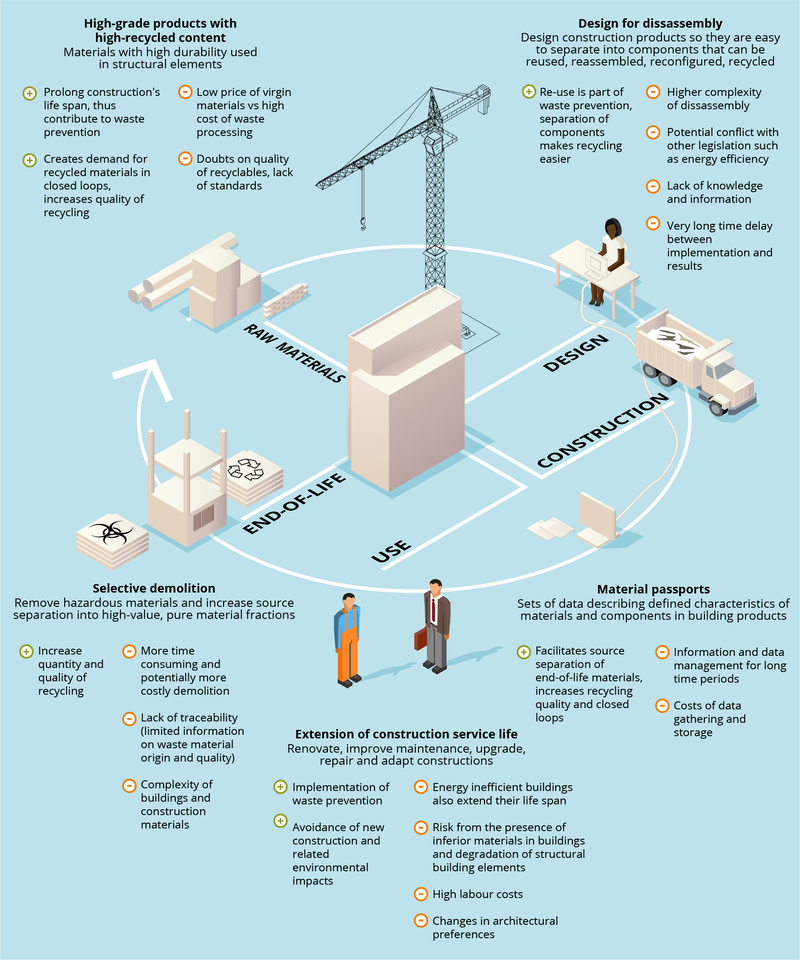

How can we improve building construction?

Three circularity objectives can be addressed through circular renovation actions:

Source: EEA briefing, 2022

Improving circularity of construction and demolition waste

Source: EEA briefing, 2020