Surface waters and groundwaters

Surface waters

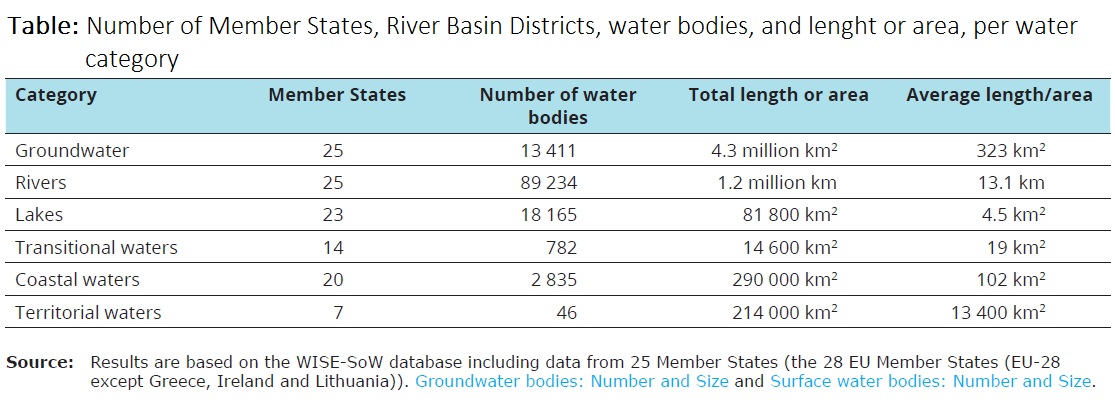

Surface waters consist of four main water categories as rivers, lakes, transitional waters, and coastal waters. They are also identified as natural, heavily modified, and artificial waters.

Rivers

A river is a body of inland water flowing for the most part on the surface of land, but which may flow underground for part of its course.

A river system comprises both the main course of the river and all the tributaries that flow into it. The area that the river system drains is known as the catchment. The main characteristic of rivers is their continuous one-way flow in response to gravity.

Because of variations in physical conditions, such as slope and bedrock geology, rivers are dynamic and may change form several times throughout their course. For example, a fast-flowing mountain stream may develop into a wide, deep and slow-flowing lowland river.

When assessing river characteristics and water quality, it is important to bear in mind that a river comprises not only a main course but also a vast number of tributaries.

Lakes

A lake is a body of standing inland surface water. Lakes are generally freshwater, but they may also be brackish, i.e. slightly salty. They are characterised by the physical features of the lake basin, such as lake area and water depth, as well as the characteristics of the catchment area, such as size and topography.

Lakes in Europe

There are more than 500 000 natural lakes larger than 0.01 km2 (1 ha) in Europe. About 80-90 % of these are small with a surface area of between 0.01 and 0.1 km2, whereas around 16 000 have a surface area exceeding 1 km2. Three quarters of Europe’s lakes are located in Finland, Norway, Sweden and the Karelo-Kola area of Russia.

The formation of Europe’s lakes

Many natural European lakes appeared 10 000-15 000 years ago. They were formed or reshaped by the last glacial period, the Weichsel, when ice covered all of northern Europe. However, in central and southern Europe, ice sheets only stretched as far as mountain ranges. As a rule, the regions comprising many natural lakes were affected by the Weichsel ice. For example, Finland, Norway, Sweden and the Karelo-Kola area of Russia have numerous lakes that account for approximately 5-10 % of the national surface areas. Large numbers of lakes were also created in other countries around the Baltic Sea, as well as in Iceland, Ireland and the northern and western parts of the United Kingdom. In central Europe, most natural lakes lie in mountain regions. Lakes at high altitude are relatively small whereas those in valleys are larger, for example Lac Léman, Bodensee, Lago di Garda, Lago di Como and Lago Maggiore in the Alps and Lake Prespa and Lake Ohrid in the Dinarian Alps. Two exceptions are the large lakes lying on the Hungarian Plain — Lake Balaton and Lake Neusiedler.

European countries that were only partially affected by the glaciation period (Belgium, Czechia, France, Portugal, Slovakia and Spain as well as southern England, central Germany, and the central European part of Russia) boast few natural lakes. In these areas, man-made lakes such as reservoirs and ponds are often more common than natural lakes. Many river valleys have been dammed to create reservoirs, a large number of which have been built in mountain ranges for hydroelectric purposes. In several countries, for example Czechia, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Slovakia, numerous small, artificial lakes have been created by other human activities such as peat and sand quarrying, and for use as fish ponds.

Transitional waters

The term transitional waters came into general use in 2000 with the publication of the WFD, which establishes a framework for the protection of all waters (including inland surface waters, transitional waters, coastal waters and groundwater). According to the WFD, ‘Transitional waters are bodies of surface water in the vicinity of river mouths which are partly saline in character as a result of their proximity to coastal waters but which are substantially influenced by freshwater flows.’ The term was designed to provide an ecologically relevant definition of the continuum between freshwaters and coastal marine waters.

Transitional waters are defined as being:

- ‘...in the vicinity of a river mouth’, meaning close to the end of a river where it mixes with coastal waters;

- ’...partly saline in character’, meaning that the salinity is generally lower than in the adjacent coastal water;

- ’...substantially influenced by freshwater flow’, meaning that there is a change in salinity or flow.

Transitional waters include a diverse range of ecosystem types, such as lagoons, fjords, brackish wetlands and river mouths, and are therefore important to a wide array of species that may reside in them or use them as, for example, spawning or nursery habitats. For sea trout and other diadromous (migrating between fresh and salt water) species such as salmon, eel, shads and lampreys, they are often thought of simply as migration pathways between freshwater and marine environments, but conditions in transitional waters may be critical for these species during this important stage in their lives.

Coastal waters

Coastal waters are defined as ‘Surface water on the landward side of a line, every point of which is at a distance of one nautical mile on the seaward side from the nearest point of the baseline from which the breadth of territorial waters is measured, extending where appropriate up to the outer limit of transitional waters.’

The ecological status of coastal waters should be classified from the landward extent of either the coastal or transitional waters out to one nautical mile from the baseline. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the baseline is measured as the low-water line except along the mouths of estuaries and heads of bays where it cuts across open water. Along highly indented coastlines, bays, mouths of estuaries or coastlines with islands, the baseline can be drawn as a straight line. Each Member State has a legislative baseline associated with this definition.

Heavily modified and artificial water bodies

Heavily modified water bodies (HMWB)

For surface waters, the overall goal of the WFD is for Member States to achieve good ecological and chemical status in all bodies of surface water. Some water bodies may not achieve this objective for different reasons. Under certain conditions, the WFD permits Member States to identify and designate artificial water bodies (AWB) and heavily modified water bodies (HMWB) according to Article 4(3). The assignment of less stringent objectives to water bodies and an extension of the timing for achieving the objectives is possible under other particular circumstances. These derogations are laid out in Articles 4(4) and 4(5) of the WFD.

HMWBs are bodies of water which, as a result of physical alterations by human activity such as irrigation, drinking water supply, power generation and navigation etc. are substantially changed in character and cannot, therefore, meet good ecological status. The environmental objective for HMWBs is good ecological potential, which has to be achieved. These activities often lead to major changes in river processes, primarily the flow of the river, the migration of animal species and the transport of particulate matter. Although the changes may not always be seen locally, they may be extensive. Downstream reaches are nearly always affected, and the impact is also felt on upstream reaches, as well as the surrounding areas.

Artificial water bodies (AWB)

AWBs are surface water bodies created by human activity where no water body existed before, such as canals etc., and which have not been created by the direct physical alteration, movement or realignment of an existing water body. Instead of good ecological status, the environmental objective for AWBs are same as that of HMWBs; i.e. they need to achieve good ecological potential.

Groundwaters

Groundwater is water located beneath the ground surface in soil pore spaces and in the fractures of geological formations.

A formation of rock or soil is called an aquifer when it can produce a usable quantity of water. Two soil layers — unsaturated and saturated zones — can be distinguished below ground level. The unsaturated zone lies nearest the surface and the gaps between soil particles are filled with both air and water. Below this layer is the saturated zone, where the gaps are filled with water. The depth at which soil pore spaces become fully saturated with water is called the water table.

Aquifers can be either unconfined (i.e. when only the bottom is confined by a layer of impervious material, so that the aquifer is in contact with the atmosphere through the unsaturated zone) and confined (i.e. when the aquifer has impervious layers both at the bottom and at the surface). Both types of aquifer have a recharge area where water infiltrates the ground surface to reach the aquifer. Groundwater recharge is dependent on precipitation and soil moisture conditions. Aquifers usually recharge slowly and mostly during the wet winter season.

Groundwater over-exploitation occurs when groundwater abstraction exceeds recharge and leads to a lowering of the groundwater table. The rapid expansion in groundwater abstraction over the past 30 to 40 years has been due to new agricultural and socioeconomic development in regions where surface water resources are insufficient, uncertain or too costly. Over-abstraction leads to a lowering of the water table, loss of wetlands dependent on groundwater and deteriorating water quality. This is a significant problem in many European countries, in particular, along the coast where the population density and the need for water are high. Over-abstraction in these areas often leads to intrusion of saltwater into aquifers making groundwater unsuitable for consumption.

See also

Document Actions

Share with others