A4.1 The '20-20-20' targets for 2020

The EU has a long-term goal of reducing Europe's GHG emissions by 80 % by 2050, compared with 1990 levels. In the context of its commitments and the negotiations at international level, in March 2007 the European Council committed the EU to becoming a highly energy-efficient, low-carbon economy by achieving three domestic climate and energy objectives by 2020 (Council of the European Union, 2007):

- to reduce GHG emissions by 20 % compared with 1990 levels;

- to increase to 20 % the share of energy from renewable sources in the EU's gross final energy consumption;

- to improve the EU's energy efficiency by 20 %.

To achieve these domestic commitments, in 2009, the EU adopted the climate and energy package, which comprises various pieces of legislation (EU, 2009a, 2009c, 2009d, 2009e, 2009f). The package introduced a clear approach to achieving the 20 % reduction in total GHG emissions, compared with 1990 levels, which is equivalent to a 14 % reduction compared with 2005 levels. This 14 % reduction objective is to be achieved through a 21 % reduction compared with 2005 levels for emissions covered by the ETS, and a 9 % reduction for sectors covered by the ESD (EU, 2009c).

A revision of the ETS Directive (EU, 2009a) introduced a single 2020 target for all EU emissions covered by the EU ETS (as well as ETS emissions from the three participating non-Member States, namely Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway). The ETS essentially covers emissions from large industrial installations, as well as emissions from aviation. ETS emissions represent about 40-45 % of total EU GHG emissions. The 2020 cap corresponds to a reduction of about 21 % in ETS emissions by 2020, compared with 2005 levels. The sectors covered under the EU ETS are therefore expected to contribute the largest proportion of emission reductions in the context of meeting the EU's 2020 GHG emissions target. For allowances allocated to the EU ETS sectors, annual caps have been set for the period from 2013 to 2020; these decrease by 1.74 % annually. For further details on the EU ETS in the period 2013-2020, see EEA, 2017k.

For all other emissions not covered by the EU ETS, the ESD has set annual binding targets for each year of the period between 2013 and 2020, for each Member State.

These EU-internal rules under the '2020 climate and energy package' underpin the EU implementation of the 2020 target under the UNFCCC (see Annex 5).

A4.2 The 2030 climate and energy framework

To ensure that the EU is cost-effectively attaining its long-term objective, EU leaders agreed, in October 2014, on a 2030 climate and energy policy framework for the EU, and endorsed the following targets (European Council, 2014):

- A binding target of at least a 40 % domestic reduction in GHG emissions, compared with 1990 levels, was agreed. The 40 % domestic reduction target for GHG emissions will ensure that the EU is on track to cost-effectively meeting its objective of cutting emissions by at least 80 % by 2050. This target will be delivered collectively, with a 43 % reduction in the ETS sectors and a 30 % reduction in the Effort Sharing sectors by 2030, compared with 2005 levels. In the EU ETS, the annual factor that reduces the cap on the maximum permitted emissions will be changed from 1.74 % to 2.2 % from 2021 onwards. In Effort Sharing sectors, the methodology for setting the national reduction targets, with all the elements as applied in the ESD for 2020, will be slightly amended for 2030. Efforts will be distributed on the basis of relative GDP per capita, but targets for Member States with a GDP per capita above the EU average will be adjusted relatively, to reflect cost-effectiveness in a fair and balanced manner. All Member States will contribute to the overall EU reduction in 2030, with the targets ranging from 0 % to -40 %, compared with 2005 levels.

- A target for renewable energy consumption of at least 27 % of total energy consumption was set. This target is binding at EU level, but there are no fixed targets for individual Member States. This target is intended to provide flexibility for Member States to set their own more ambitious national objectives for increased renewable energy use, and to support them, in line with the state aid guidelines, as well as take into account their degree of integration in the internal energy market.

- The European Council endorsed a target at EU level of 30 % for improving energy efficiency, compared with projections of future energy consumption, based on the current criteria (i.e. projections of energy consumption in 2030 from the 2007 Energy Baseline Scenario from the European Commission) (European Council, 2017).

Neither the renewable energy target nor the energy efficiency target will be translated into nationally binding targets. Individual Member States are free to set their own higher national targets.

These targets for 2030 were submitted to the UNFCCC on 6 March 2015 as an INDC for the Paris Agreement of December 2015.

The European Commission proposed in 2016 to integrate the LULUCF sector into the EU 2030 climate and energy framework from 2021 onwards. The current proposal (EC, 2016i) suggests a 'no debit rule' requiring each Member State to compensate net accounted emissions from the LULUCF sector by emission reductions in Effort Sharing sectors (see Section 2.5). The proposal also includes modified accounting rules.

The adoption of the Framework Strategy for a Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy (EC, 2015b) underlined the importance of meeting the 2030 targets, as 'Energy Union and Climate' was identified as one of 10 priorities at the start of the Juncker Commission's term. This priority comprises five 'dimensions' (i.e. 'supply security', 'a fully integrated internal energy market', 'energy efficiency', 'climate action — emission reduction' and 'research and innovation'), which have been henceforth reported on annually in the State of the Energy Union (latest report from 2017: EC, 2017c). The annual reporting of progress is considered essential so that issues can be identified in a timely fashion and addressed, if necessary, through further policy interventions.

A4.3 National targets and compliance under the Effort Sharing Decision

A4.3.1 Targets for 2020

The ESD covers emissions from all sources outside the EU ETS, except for emissions from aviation [1] and international maritime transport, and net emissions from LULUCF. The ESD therefore includes a range of diffuse sources in a wide range of sectors such as transport (cars, trucks), buildings (in particular heating), services, small industrial installations, agriculture and waste. Such sources currently account for almost 60 % of total GHG emissions in the EU.

The ESD sets individual annual binding targets for GHG emissions not covered by the EU ETS for all Member States for the period from 2013 to 2020 (AEAs) (EU, 2009c). In 2013, the European Commission determined the AEAs of Member States for the period from 2013 to 2020, using reviewed and verified emission data for the years 2005, 2008, 2009 and 2010 (EU, 2013a). The AEAs were adjusted in 2013 to reflect the change in ETS scope from 2013 onwards (EU, 2013b) [2] and in 2017 to reflect updates in methodologies for reporting of GHG inventories (EU, 2017b).

Each Member State will contribute to this effort, according to its relative wealth in terms of GDP per capita. The national emission targets range from a 20 % reduction for the richest Member States to a 20 % increase for the poorest ones by 2020, compared with 2005 levels (see Figure A4.1). At EU level, this will deliver approximately 9.3 % emission reductions by 2020, compared with 2005 levels, from those sectors covered by the ESD. The least wealthy countries are allowed to increase emissions in these sectors because their relatively high economic growth is likely to be accompanied by higher emissions. Nevertheless, their targets still represent a limit on emissions, and a reduction effort will be required by all Member States; they will need to introduce policies and measures to limit or lower their emissions in the various ESD sectors.

A4.3.2 Proposed 2030 targets

On 20 July 2016, the European Commission presented a legislative proposal, the 'Effort Sharing Regulation', which sets out binding annual GHG emission targets for Member States for the period 2021-2030 (EC, 2016g). The proposal is the follow-up to the ESD, which established national emission targets for Member States in Effort Sharing sectors between 2013 and 2020. The proposal recognises the different capacities of Member States to take action by differentiating targets according to GDP per capita across Member States. This ensures fairness because Member States with the highest incomes take on more ambitious targets than Member States with lower incomes. EU leaders recognised that an approach for high-income Member States based solely on relative GDP per capita would mean that, for some, the costs associated with reaching their targets would be relatively high. To address this, these targets have been adjusted to reflect cost-effectiveness for Member States with an above average GDP per capita. In line with the guidance of the European Council, the resulting 2030 GHG emission targets range from 0 % to –40 %, compared with 2005 levels (see Figure A4.1).

A4.3.3. Allowed flexibilities under the ESD

The ESD allows Member States to use flexibility provisions to meet their annual targets, with certain limitations:

- Within the Member State itself, any overachievement in a year during the period from 2013 to 2019 can be carried over to subsequent years, up to 2020. Up to 5 % of a Member State's annual emission allocation may be carried forward to the following year during the period from 2013 to 2019. Where the emissions of a Member State are below that annual emission allocation, excess emission reductions can be carried over to the subsequent years.

- Member States may transfer up to 5 % of their AEAs to other Member States, which may use this emission allocation until 2020 (ex ante). Any overachievement in a year during the period 2013-2019 may also be transferred to other Member States, which may use this emission allocation until 2020 (ex post).

Member States may use emission credits from the Kyoto Protocol's flexible mechanisms in accordance with the following provisions:

- The use of project-based emission credits is capped on a yearly basis up to 3 % of 2005 ESD emissions in each Member State.

- Member States that do not use their 3 % limit for project-based credits in any specific year can transfer their unused credits for that year to other Member States, or bank it for their own use until 2020.

- Member States fulfilling additional criteria (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden) may use credits from projects in least developed countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS) for up to an additional 1 % of their verified emissions in 2005. These credits are not bankable or transferable.

Overall, a maximum of Kyoto emission credits equivalent to 750 Mt CO2 at EU level can be used during the period 2013-2020. As most Member States are expected to meet their ESD targets (see Section 3.1) without the flexibility provisions, while other Member States can meet their ESD targets through intra-EU transfers of AEAs, the use of project credits is expected to be significantly smaller.

Any Member State exceeding its annual AEA, even after taking into account the flexibility provisions and the use of Kyoto Protocol emission credits, will have to take corrective measures as laid down in the ESD and will be subject to the following consequences:

- a deduction from the AEA for the next year of the excess Effort Sharing emissions multiplied by 1.08 (8 % interest rate);

- the development of a corrective action plan — the European Commission may issue an opinion, possibly taking into account comments from the Climate Change Committee;

- the transfer of emission allocations and project-based credits from the account of that Member State will be temporarily suspended while the Member State is in a state of non-compliance with its ESD obligations.

The proposed 'Effort Sharing Regulation' for 2030 targets maintain existing flexibilities under the current ESD (e.g. banking, borrowing, buying and selling) and provides two new flexibilities to allow for a fair and cost-efficient achievement of the targets. These new flexibilities are as follows:

- A new one-off flexibility to access allowances from the EU ETS: this allows eligible Member States to achieve their national targets by covering some emissions in the Effort Sharing sectors with EU ETS allowances that would normally be auctioned. The amount of allowances used for that purpose may not exceed 100 million tonnes of CO2 over the period 2021-2030 in the whole EU. Eligible Member States have to notify the Commission before 2020 of the amount of the allowances they aim to use under this flexibility over the period. Since the transfer is strictly limited in volume, and decided beforehand, predictability and environmental integrity are maintained.

- A new flexibility to access credits from the land use sector: to stimulate additional action in the land use sector, the proposal allows Member States to use up to 280 million credits over the entire period 2021-2030 from certain land use categories to comply with their national targets. All Member States are eligible to make use of this flexibility, but more access is available for Member States with a larger proportion of emissions from agriculture. In line with EU leaders' guidance, this recognises that there is a relatively low mitigation potential for emissions from the agriculture sector.

Notes: The targets are expressed relative to 2005 ESD base-year emissions. These base-year emissions are calculated on the basis of relative and absolute 2020 targets (for details on ESD base-year emissions, please see Section A1.2 in Annex 1).

The absolute 2020 and 2013 targets used for the calculations are consistent with the global warming values in the IPCC AR4 (IPCC, 2007) and take into account the change in the scope of the ETS from the second to the third period (2013 to 2020).

Sources: EC, 2016g; EU, 2009c.

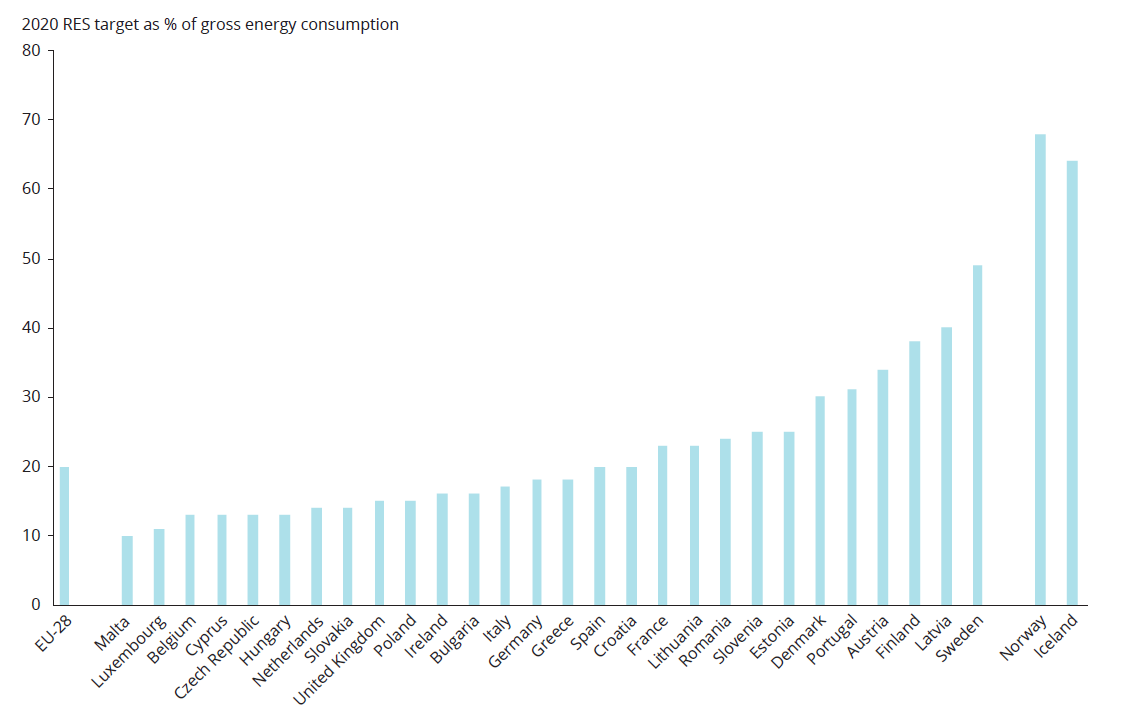

A4.4 Renewable energy targets for 2020

To meet its target of increasing the use of RES to 20 % of gross final energy consumption by 2020, the EU adopted the RED (EU, 2009d) as part of the climate and energy package.

The RED includes legally binding national renewable energy targets for 2020, consistent with an EU-wide target of increasing RES use to 20 % of gross final energy consumption by 2020, and to 10 % of transport-related fuel consumption by the same year (EU, 2009c). The RED also sets an indicative trajectory for each Member State for the period 2011-2018, intended to ensure that each Member State achieves its 2020 targets. An interim indicative RED target for the EU can be derived from the minimum indicative trajectories of the Member States in the run-up to 2020 (RED, Annex I, Part B).

Under the RED, Member States had to submit NREAPs in 2010 (EEA, 2011). These plans outline the pathways (i.e. the expected trajectories) that Member States anticipate using to reach their legally binding national renewable energy targets by 2020. In 2011 (and every 2 years thereafter), Member States had to report on national progress towards the interim RED and expected NREAP targets. The NREAPs adopted by Member States in 2010 outline the expected trajectories for RES use, as a proportion of gross final energy consumption, towards the legally binding national 2020 RES targets.

In contrast, no national targets for renewable energy have been set for 2030.

Notes: The targets for Iceland and Norway, which are not EU Member States, were agreed and are included in the annex of the European Economic Area agreement. For the sake of simplicity, the report refers to these as RED targets.

RES, renewable energy source.

Source: EU, 2009d.

A4.5 Energy efficiency targets for 2020

In 2007, the European Council stressed the need to increase energy efficiency to achieve the 20 % energy savings target for 2020, for primary energy consumption, and agreed on binding targets for GHG emission reductions and renewable energy (Council of the European Union, 2007). The reduction of primary energy consumption by 20 % by 2020 is a non-binding objective in the EU.

The climate and energy package does not address the energy efficiency target directly, although the CO2 performance standards for cars and vans (EU, 2009f, 2014a), the revised EU ETS Directive and the ESD all contribute to fostering energy efficiency. Since the adoption of the package, the EU energy efficiency policy framework has advanced in line with the priorities identified in the Action Plan for Energy Efficiency 2006 (EC, 2006). The energy efficiency action plan was reviewed in 2011, after revisions of the following pieces of legislation:

- the Ecodesign Directive (EU, 2009g, 2012);

- the Energy Labelling Directive (EU, 2010a);

- the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) (EU, 2010b).

One of the key developments in the energy efficiency policy framework was the adoption of the EED in 2012 (EU, 2012). The EED establishes a common framework of measures for the promotion of energy efficiency within the EU and aims to help remove barriers and overcome market failures that impede efficiency in the supply and use of energy. The EED stipulates that primary energy consumption in the EU should not exceed 1 483 Mtoe in 2020, and that final energy consumption in the EU should not exceed 1 086 Mtoe in 2020. These absolute targets were set using the European Commission’s 2007 Energy Baseline Scenario (EC, 2008), based on the Price-driven and Agent-based Simulation of Markets Energy System Models (PRIMES). Implementing the EED was expected to lead to a 15 % reduction in primary energy consumption compared with the 2007 Energy Baseline Scenario, with an additional 2 % reduction expected from the transport sector (Groenenberg, 2012).

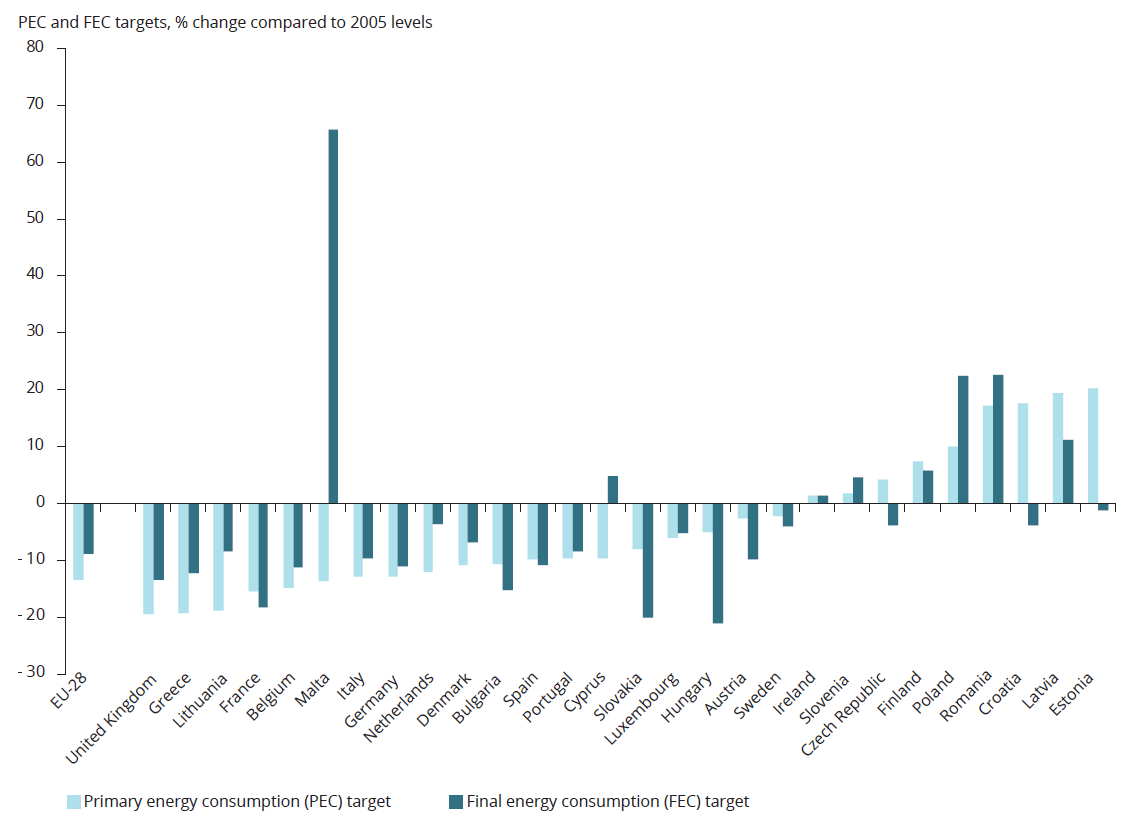

Under the EED, Member States had to set indicative national targets and implement a set of mandatory requirements, one of the most significant being the establishment of an Energy Efficiency Obligation (EEO) scheme, or the implementation of alternative measures.

Member States have adopted various base years against which the progress towards national energy efficiency targets will be measured. Member States also chose different approaches for setting national targets. A total of 10 Member States (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Malta and Poland) chose to focus their targets on primary energy consumption, while 12 (Croatia, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Slovakia, Slovenia and the United Kingdom) chose to focus their national targets on gross final energy consumption. Another two (Bulgaria and Sweden) have focused on primary energy intensity. Each national target reflects the specific situation of the Member State that adopted it. As a consequence, ambition levels vary greatly. Compared with 2005 levels, currently 18 Member States have aimed to reduce final as well as primary energy consumption; for six Member States, targets show an increase in final as well as primary energy consumption. Four other Member States intend to keep the potential increase in either primary or final energy consumption to a certain limit over the period.

In some Member States, the targets are still subject to change. This is because some countries are currently holding nationwide debates on the future of their energy systems and they are allowed to adjust their targets when they review their triennial NEEAPs submitted under the EED. In fact, in 2017, 18 Member States had submitted their revised NEEAPs before the finalising of this report.

Figure A4.3 shows the national targets set by each Member State under the EED, compared with 2005 levels, for primary and final energy consumption. The year 2005 is used here to serve as a common reference, although the EED does not explicitly use it as a common base year.

In contrast, no national targets for energy efficiency have been set for 2030 (see Section 1.2).

Note: The national targets for 2020 reported by Member States under the EED were first calculated in absolute terms and then compared with 2005 levels.

Sources: EC, 2015c, 2017d, 2017e; EU, 2012; Eurostat, 2017a, 2017b, 2017c.

A4.6 Overview of 2020 national climate and energy targets

The main targets that apply to Member States under international and EU commitments are presented in Table A4.1. The scope of existing EU legislation that implements a domestic 20 % target commitment is different from that of the Kyoto target for the second commitment period. For this reason, the total allowed emissions or the ‘emissions budget’ under the climate and energy package cannot be directly compared with the corresponding quantified emission limitation or reduction commitment (QELRC). Some of the main differences between the climate and energy package and the second commitment period, in terms of emissions included and the methodologies used to determine emissions, relate to the treatment of emissions from international aviation, emissions and removals from LULUCF, the use of units from flexible mechanisms, the coverage of NF3, flexibilities regarding base years and the use of GWP. The differences are summarised in Table A4.5. For details, please see EEA, 2014b, as well as Annex 5.

|

|

Participating in EU ETS

|

ETS target (2020)

|

ESD target (2020)

|

2020 ESD emission allocation

|

2005 ESD base-year emissions

|

Renewable target 2020 (RED)

|

Primary energy target 2020

|

Final energy target 2020

|

|

|

|

% vs. 2005

|

Mt

|

% gross final energy consumption

|

Mtoe

|

|

EU-28

|

|

-21

|

9

|

2 618.2

|

2 887.1

|

20

|

1 483

|

1 086

|

|

Austria

|

x

|

|

-16

|

47.8

|

56.8

|

34

|

32

|

25

|

|

Belgium

|

x

|

|

-15

|

68.2

|

80.3

|

13

|

44

|

33

|

|

Bulgaria

|

Since 2007

|

|

20

|

26.5

|

22.1

|

16

|

17

|

9

|

|

Croatia

|

Since 2013

|

|

11

|

19.3

|

17.4

|

20

|

11

|

7

|

|

Cyprus

|

x

|

|

-5

|

4.0

|

4.2

|

13

|

2

|

2

|

|

Czech Republic

|

x

|

|

9

|

67.2

|

61.7

|

13

|

44

|

25

|

|

Denmark (a)

|

x

|

|

-20

|

32.1

|

40.1

|

30

|

17

|

14

|

|

Estonia

|

x

|

|

11

|

6.0

|

5.4

|

25

|

7

|

3

|

|

Finland

|

x

|

|

-16

|

28.5

|

33.9

|

38

|

36

|

27

|

|

France

|

x

|

|

-14

|

342.5

|

398.2

|

23

|

220

|

131

|

|

Germany

|

x

|

|

-14

|

410.9

|

477.8

|

18

|

277

|

194

|

|

Greece

|

x

|

|

-4

|

60.0

|

62.6

|

18

|

25

|

18

|

|

Hungary

|

x

|

|

10

|

52.8

|

48.0

|

13

|

24

|

14

|

|

Ireland

|

x

|

|

-20

|

37.7

|

47.1

|

16

|

15

|

13

|

|

Italy

|

x

|

|

-13

|

291.0

|

334.5

|

17

|

158

|

124

|

|

Latvia

|

x

|

|

17

|

10.0

|

8.5

|

40

|

5

|

5

|

|

Lithuania

|

x

|

|

15

|

15.2

|

13.3

|

23

|

7

|

4

|

|

Luxembourg

|

x

|

|

-20

|

8.1

|

10.1

|

11

|

5

|

4

|

|

Malta

|

x

|

|

5

|

1.2

|

1.1

|

10

|

1

|

1

|

|

Netherlands

|

x

|

|

-16

|

107.4

|

127.8

|

14

|

58

|

52,2

|

|

Poland

|

x

|

|

14

|

205.2

|

180.0

|

15

|

96

|

72

|

|

Portugal

|

x

|

|

1

|

49.1

|

48.6

|

31

|

23

|

17

|

|

Romania

|

Since 2007

|

|

19

|

89.8

|

75.5

|

24

|

43

|

30

|

|

Slovakia

|

x

|

|

13

|

25.9

|

23.0

|

14 %

|

16

|

9

|

|

Slovenia

|

x

|

|

4

|

12.3

|

11.8

|

25

|

7

|

5

|

|

Spain

|

x

|

|

-10

|

212.4

|

236.0

|

20

|

123

|

87

|

|

Sweden

|

x

|

|

-17

|

36.1

|

43.5

|

49

|

48

|

32

|

|

United Kingdom (a)

|

x

|

|

-16

|

350.9

|

417.8

|

15

|

180

|

132

|

|

EEA member countries

|

|

Iceland

|

Since 2008

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Liechtenstein

|

Since 2008

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Norway

|

Since 2008

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Switzerland

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Turkey

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes: (a) The Faroe Islands and Greenland (Denmark), and the United Kingdom’s overseas territories, are not part of the EU and therefore are not covered by the targets presented here.

ESD, Effort Sharing Decision; EU ETS, European Union Emissions Trading System; Mtoe, million tonnes of oil equivalent; RED, Renewable Energy Directive.

Sources: EC, 2017d; EU, 2009a, 2009c, 2009d, 2012, 2013a, 2013b.

Document Actions

Share with others