-

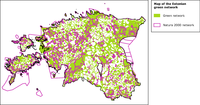

The map reflects the spatial combination of sites designated under national instruments and Natura 2000 sites. In France Natura 2000 extends significantly beyond existing national designations, as shown by the extend of light green on the map. As compared to the map showing the overlap with only IUCN categories I to IV, its is obvious that, particularly in th South-eastern part of France, several Natura 2000 sites overlap with nationally designated sites under categories V and VI. There are also a large part of nationally designated sites under IUCN V and VI which are not designated as Natura 2000 as reflected by the blue dots on the map.

This diagramme shows the range of surface area covered by nationally designated areas in four different and contrasting EEA member countries. Bulgaria has 80% of its protected areas under 100 ha and none over 1000ha whereas Greece has 94% of its protected areas above 100ha and 7% over 10 000 ha. Italy and Poland show the largest range of size of protected area between less than 1 ha and more than 10 000 ha

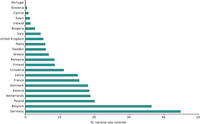

In terms of overall number, Estonia, Norway, Slovakia and Sweden have the most protected areas classified

as Category Ia and Ib, and Category II. Albania, Bulgaria, Estonia and Slovenia have the highest number

of protected areas under Category III, but not all countries classify protected areas under this category.

The United Kingdom is the only country within the 39 EEA member and collaborating countries that has no

protected areas in categories I, II or III. No data available for Ireland.

-

-

-

-

-

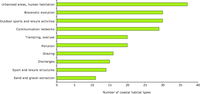

This diagram shows the number of marine species affected by pressures reported by 40% of EU countries where these species occur.

These broad ecosystem‑types represent different ways of clustering CLC units, so there are overlaps between them. For

instance, 'grasslands' and part of 'heaths and scrubs' are included in 'agro-ecosystems'. Similarly, 'lakes and rivers' are

included in 'wetlands'. This is why the sum of the ecosystems is over 100 %.

This diagramme shows the change in area covered by broad ecosystem-types between 2000 and 2009 inside and outside nationally designated areas. The way how “broad ecosystem-types” are defined is described in the EU 2010 Biodiversity Baseline (http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eu-2010-biodiversity-baseline).

Climate change is one of the main factors that will affect biodiversity in the future and may even cause species extinctions. We suggest a methodology to derive a general relationship between biodiversity change and global warming. In conjunction with other pressure relationships, our relationship can help to assess the combined effect of different pressures to overall biodiversity change and indicate areas that are most at risk. We use a combination of an integrated environmental model (IMAGE) and climate envelope models for European plant species for several climate change scenarios to estimate changes in mean stable area of species and species turnover. We show that if global temperature increases, then both species turnover will increase, and mean stable area of species will decrease in all biomes. The most dramatic changes will occur in Northern Europe, where more than 35% of the species composition in 2100 will be new for that region, and in Southern Europe, where up to 25% of the species now present will have disappeared under the climatic circumstances forecasted for 2100. In Mediterranean scrubland and natural grassland/steppe systems, arctic and tundra systems species turnover is high, indicating major changes in species composition in these ecosystems. The mean stable area of species decreases mostly in Mediterranean scrubland, grassland/steppe systems and warm mixed forests.

Protected areas today cover a relatively large part of Europe, with almost 21 % of the territory of EEA member countries and collaborating countries consisting of protected areas. In spite of this widespread presence of protected areas in all European countries, the topic has not received as much attention on a pan-European level as other environmental issues. We hope this report from the EEA the first we have compiled on the subject will go some way to redressing the balance. The report provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of protected areas and aims to assist policymakers and the wider public in understanding the complexity of the current systems of protected areas.

The distributions of many terrestrial organisms are currently shifting in latitude or elevation in response to changing climate. Using a meta-analysis, we estimated that the distributions of species have recently shifted to higher elevations at a median rate of 11.0 meters per decade, and to higher latitudes at a median rate of 16.9 kilometers per decade. These rates are approximately two and three times faster than previously reported. The distances moved by species are greatest in studies showing the highest levels of warming, with average latitudinal shifts being generally sufficient to track temperature changes. However, individual species vary greatly in their rates of change, suggesting that the range shift of each species depends on multiple internal species traits and external drivers of change. Rapid average shifts derive from a wide diversity of responses by individual species.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts an increase in global temperatures of between 1.4°C and 5.8°C during the 21st century, as a result of elevated CO 2 levels. Using bioclimatic envelope models, we evaluate the potential impact of climate change on the distributions and species richness of 120 native terrestrial non-volant European mammals under two of IPCC’s future climatic scenarios. Assuming unlimited and no migration, respectively, our model predicts that 1% or 5–9% of European mammals risk extinction, while 32–46% or 70–78% may be severely threatened (lose > 30% of their current distribution) under the two scenarios. Under the no migration assumption endemic species were predicted to be strongly negatively affected by future climatic changes, while widely distributed species would be more mildly affected. Finally, potential mammalian species richness is predicted to become dramatically reduced in the Mediterranean region but increase towards the northeast and for higher elevations. Bioclimatic envelope models do not account for non-climatic factors such as land-use, biotic interactions, human interference, dispersal or history, and our results should therefore be seen as first approximations of the potential magnitude of future climatic changes.

Aim We investigate the importance of interacting species for current and potential future species distributions, the influence of their ecological characteristics on projected range shifts when considering or ignoring interacting species, and the consistency of observed relationships across different global change scenarios.

Location Europe.

Methods We developed ecological niche models (generalized linear models) for 36 European butterfly species and their larval host plants based on climate and land-use data. We projected future distributional changes using three integrated global change scenarios for 2080. Observed and projected mismatches in potential butterfly niche space and the niche space of their hosts were first used to assess changing range limitations due to interacting species and then to investigate the importance of different ecological characteristics.

The overarching aim of the atlas is to communicate the potential risks of climatic change to the future of European butterflies. The main objectives are to: (1) provide a visual aid to discussions on climate change risks and impacts on biodiversity and thus contribute to risk communication as a core element of risk assessment; (2) present crucial data on a large group of species which could help to prioritise conservation efforts in the face of climatic change; (3) reach a broader audience through the combination of new scientific results with photographs of all treated species and some straight forward information about the species and their ecology. The results of this atlas show that climate change is likely to have a profound effect on European butterflies. Ways to mitigate some of the negative impacts are to (1) maintain large populations in diverse habitats; (2) encourage mobility across the landscape; (3) reduce emissions of greenhouse gasses; (4) allow maximum time for species adaptation; (4) conduct further research on climate change and its impacts on biodiversity. The book is a result of long-term research of a large international team of scientists, working at research institutes and non-governmental organizations, many within the framework of projects funded by the European Commission.

Climate changes have profound effects on the distribution of numerous plant and animal species. However, whether and how different taxonomic groups are able to track climate changes at large spatial scales is still unclear. Here, we measure and compare the climatic debt accumulated by bird and butterfly communities at a European scale over two decades (1990–2008). We quantified the yearly change in community composition in response to climate change for 9,490 bird and 2,130 butterfly communities distributed across Europe 4 . We show that changes in community composition are rapid but different between birds and butterflies and equivalent to a 37 and 114 km northward shift in bird and butterfly communities, respectively. We further found that, during the same period, the northward shift in temperature in Europe was even faster, so that the climatic debts of birds and butterflies correspond to a 212 and 135 km lag behind climate. Our results indicate both that birds and butterflies do not keep up with temperature increase and the accumulation of different climatic debts for these groups at national and continental scales.

Static networks of nature reserves disregard the dynamics of species ranges in changing environments. In fact, climate warming has been shown to potentially drive endangered species out of reserves . Less attention has been paid to the related problem that a warmer climate may also foster the invasion of alien species into reserve networks. Here, we use niche-based predictive modelling to assess to which extent the Austrian Natura 2000 network and a number of habitat types of conservation value outside this network might be prone to climate warming driven changes in invasion risk by Robinia pseudacacia L., one of the most problematic alien plants in Europe.

Results suggest that the area potentially invaded by R. pseudacacia will increase considerably under a warmer climate . Interestingly, invasion risk will grow at a higher than average rate for most of the studied habitat types but less than the national average in Natura 2000 sites. This result points to a potential bias in legal protection towards high mountain areas which largely will remain too cold for R. pseudacacia . In contrast, the selected habitat types are more frequent in montane or lower lying regions, where R. pseudacacia invasion risk will increase most pronouncedly.

We conclude that management plans of nature reserves should incorporate global warming driven changes in invasion risk in a more explicit manner. In case of R. pseudacacia , reducing propagule pressure by avoiding purposeful plantation in the neighbourhood of reserves and endangered habitats is a simple but crucial measure to prevent further invasion under a warmer climate .

Document Actions

Share with others