Quality of European bathing waters remains high

Bathing water quality in Europe has improved markedly over the last decades. Systematic monitoring and management introduced under the Bathing Water Directive (BWD), (EU, 2006) large investments in urban waste water treatment plants and improvements in waste water networks have led to a drastic reduction in organic pollutants released through untreated or partially treated urban waste waters. Thanks to these continuous efforts, bathing is today possible in urbanised and formerly heavily polluted surface waters. This suggests how solid and well-implemented policies can make a difference.

The impacts of chemical pollution in inland and coastal waters on both health and biodiversity are currently being assessed under the review of the Environmental Quality Standards Directive and Ground Water Directive.

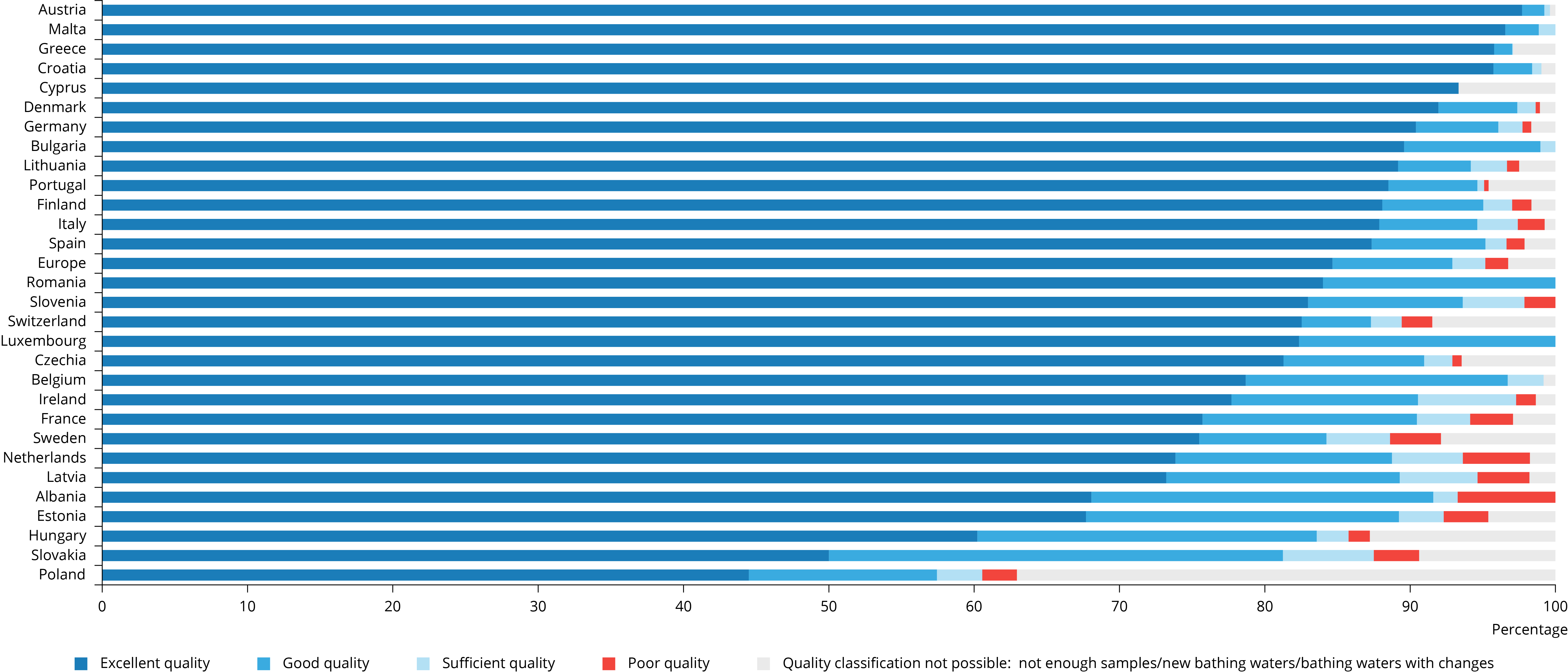

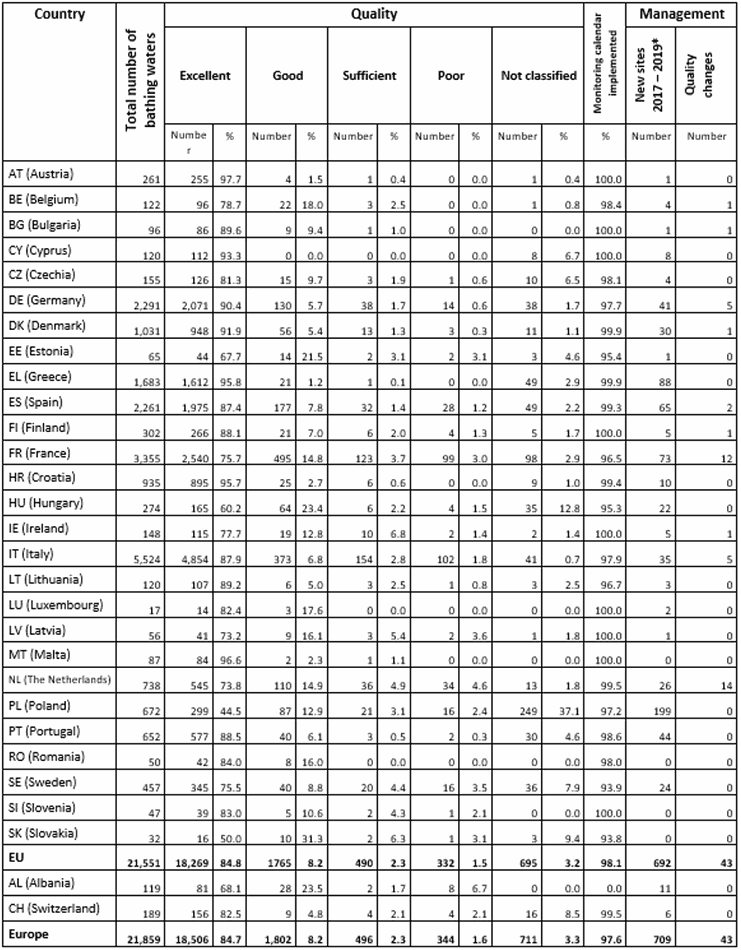

Source: WISE bathing water quality database (data from 2021 annual reports by EU Member States [1], Albania and Switzerland).

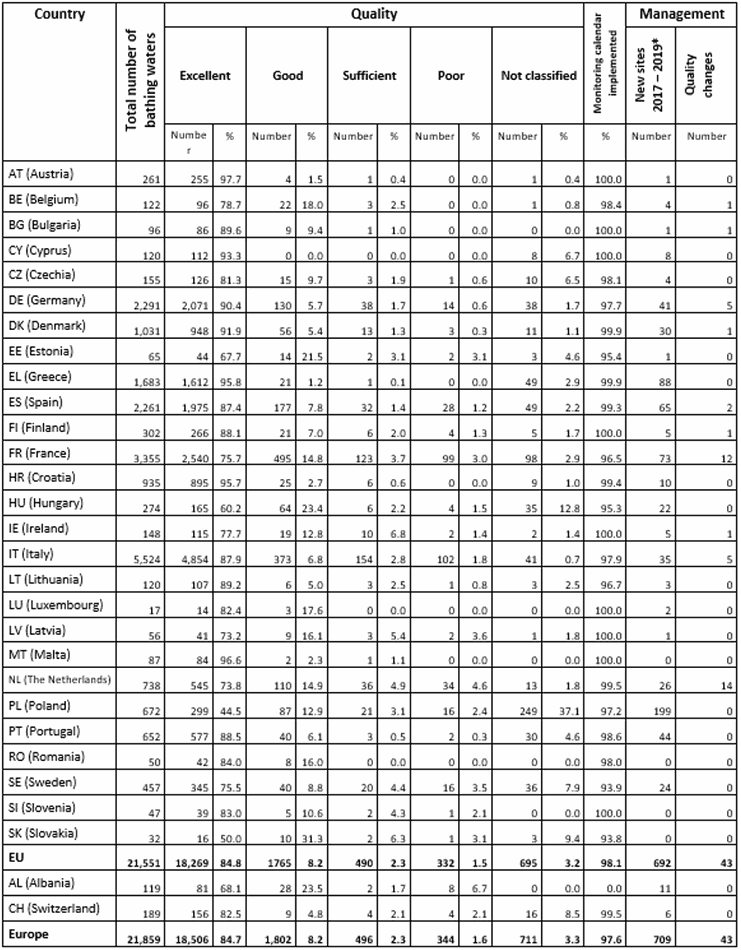

Note: The assessment covers 21,859 bathing waters in Europe that were reported to the EEA for the 2021 season. In the EU Member States, there were in total 21,551 bathing waters (Austria: 261, Belgium: 122, Bulgaria: 96, Croatia: 935, Cyprus: 120, Czechia: 155, Denmark: 1,031, Estonia: 65, Finland: 302, France: 3,355, Germany: 2,291, Greece: 1,683, Hungary: 274, Ireland: 148, Italy: 5,524, Latvia: 56, Lithuania: 120, Luxembourg: 17, Malta: 87, The Netherlands: 738, Poland: 672, Portugal: 652, Romania: 50, Slovakia: 32, Slovenia: 47, Spain: 2,261 and Sweden: 457). Outside the EU, 308 bathing waters were reported (Albania: 119 and Switzerland: 189). In Poland, only 423 out of 672 bathing waters were quality assessed which explains the low proportion of excellent quality in this country. The majority of them were newly identified and did not have complete sets of samples that would allow an assessment required by the BWD for the classification.

More info...

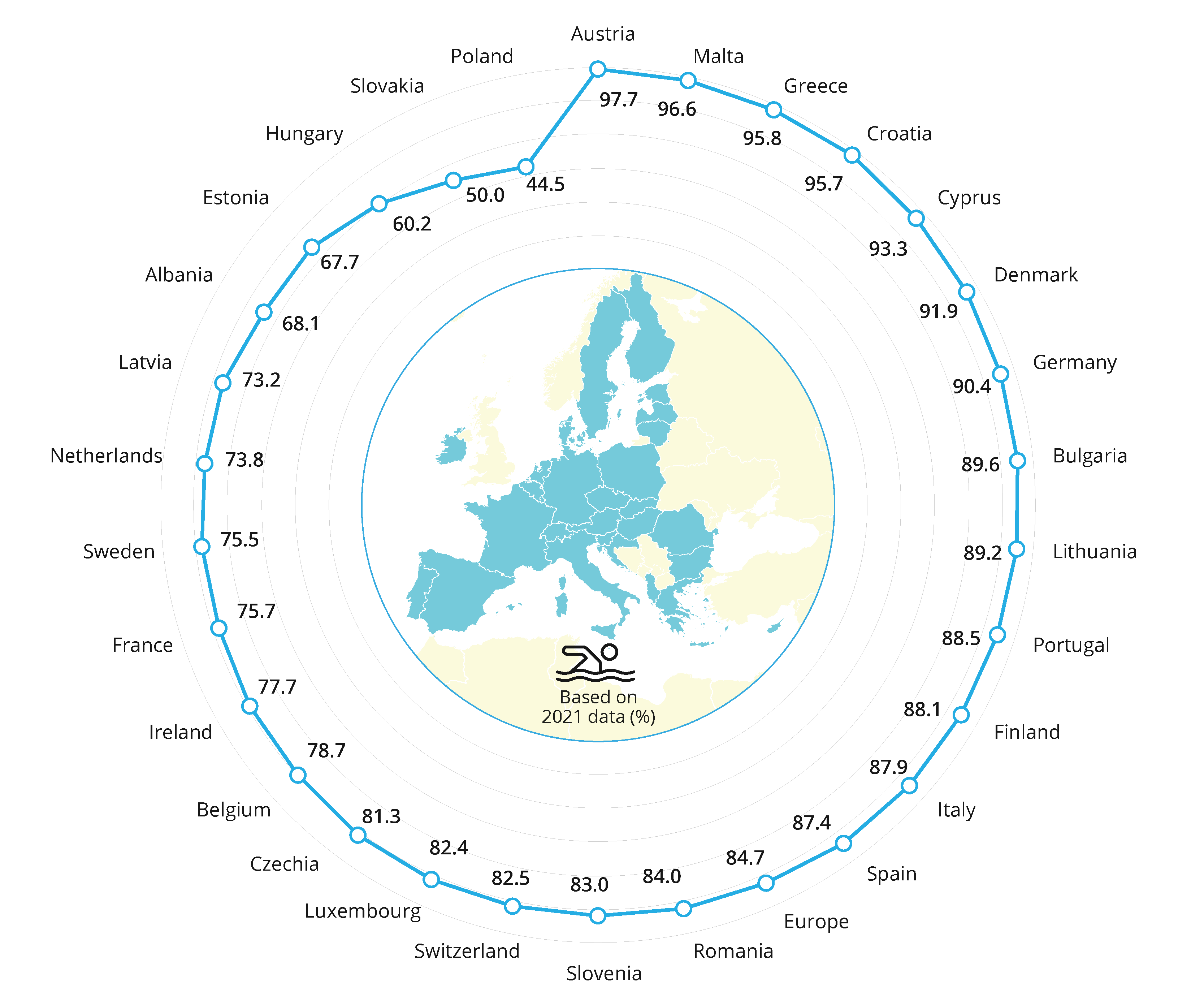

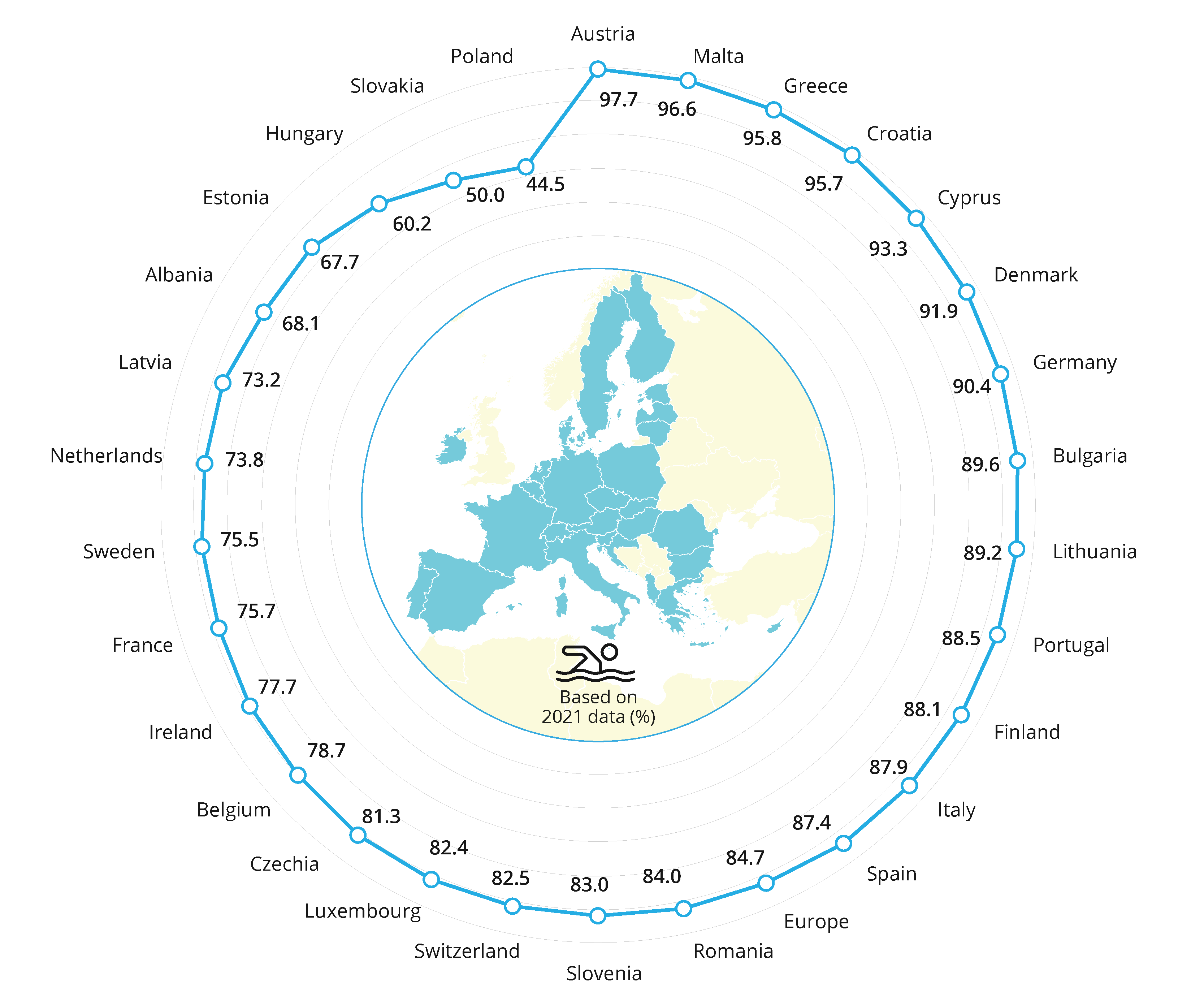

Out of 21,859 bathing sites in Europe in 2021, 84.7% were of excellent quality (Figure 1). In four countries, 95% or more, of bathing waters were of excellent quality: Austria, Malta, Croatia and Greece. Additionally in Malta, Bulgaria, Romania and Luxembourg, all assessed bathing water sites were of at least sufficient quality in 2021 (Figure 2). The percentage of European bathing waters achieving at least 'sufficient' quality (the minimum quality standard set by the Directive) increased from just 74% in 1991 to over 95% in 2003 and has remained quite stable since then.

One of the main requirements of the Directive is to ensure that all bathing water sites were at least of 'sufficient' quality by 2015. In the 2021bathing season, this minimum quality standard was met by 95.2% of all EU bathing water sites.

Source: WISE bathing water quality database (data from 2021 annual reports by EU Member States[1], Albania and Switzerland).

More info...

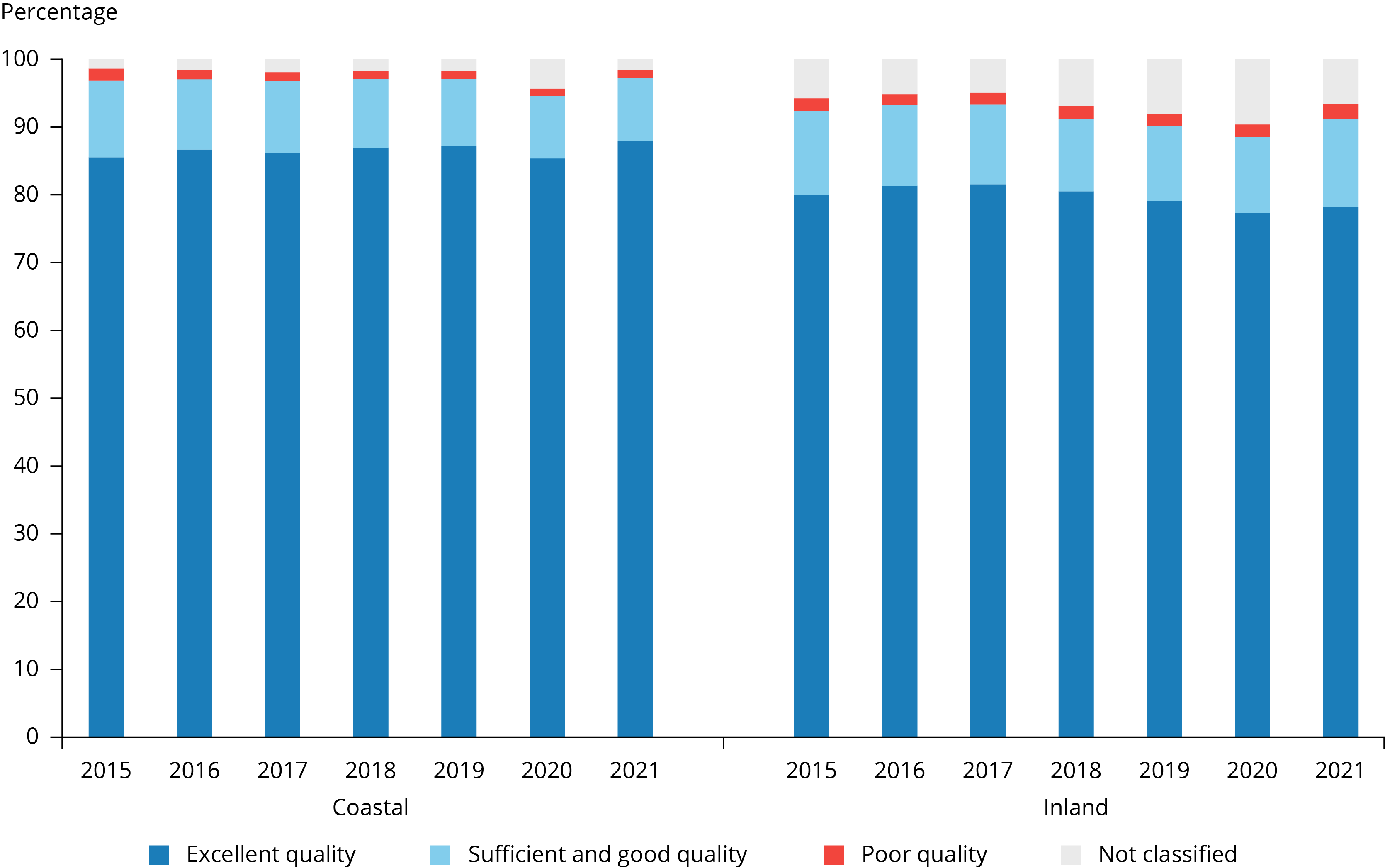

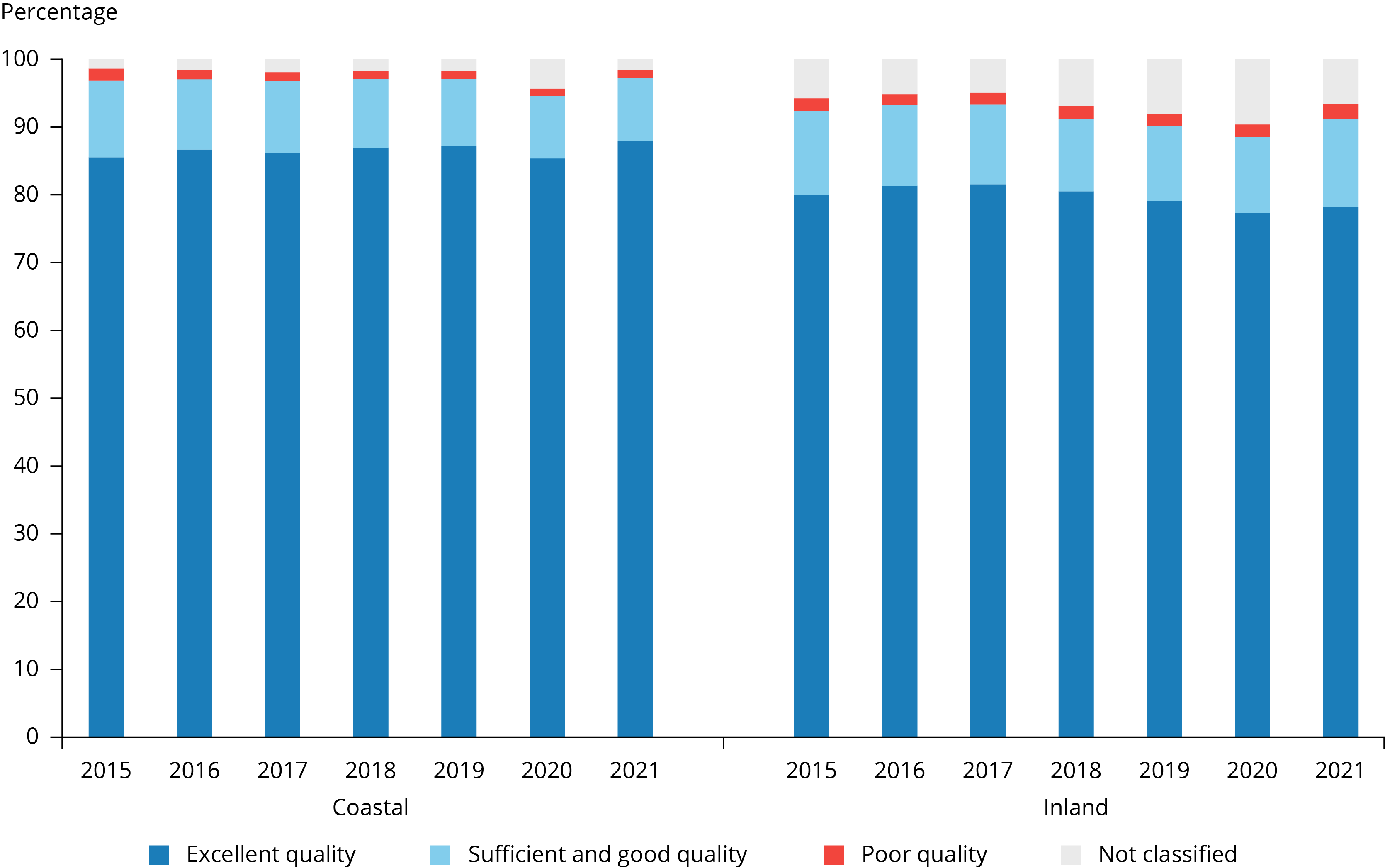

In the period 2015-2021, the share of bathing waters having an excellent status in Europe has been stable at 85-88% for coastal bathing waters; and at 77-82% for inland bathing waters (Figure 3). The quality of coastal sites is generally better than that of inland sites due to the higher self-purification capacity of coastal areas. Moreover, many central European inland bathing water sites are situated on relatively small lakes and ponds as well as rivers with a low flow, which, especially in the summer, are more susceptible than coastal areas to short-term pollution caused by heavy summer rains or droughts.

Source: WISE bathing water quality database (data from 2021 annual reports by EU Member States).

Note: There were 14,471 coastal and 7,080 inland bathing waters in the EU in the 2021 season. In the previous years, the share of coastal and inland bathing waters was similar to 2021: two thirds were coastal and one third were inland bathing waters.

More info...

How do we assess the shares of bathing water quality classes?

The number of reported bathing waters has been varying annually, increasing throughout the 1990s and 2010s. Starting with 3,984 bathing waters for the 1990 season and reaching a peak of 22,781 bathing waters in 2009, it has stabilised since then at roughly 22, 000bathing waters. The change compared to the previous season (2020) can be described with the following key messages.

There is a decrease of 1.9% in the total number of bathing waters, characterised by the removal of the United Kingdom on the one hand (640 bathing waters reported for 2020, and none for the most recent season); and newly identified bathing waters on the other hand, most notably in Greece (49 bathing waters), France and Spain (35), Poland (34) and Portugal (21).

Bathing waters with no quality classification are a notable part of an overall bathing water inventory. The reason for the lack of classification is a missing sample dataset, especially prominent in the 2020 season because of Covid-19 related restrictions (including prohibited access for both bathing and sampling). There were 1,342 bathing waters not classified in the 2020season, followed by 711 in the most recent season (2021). There is an increase in the number of poor-quality bathing waters from 296 to 344 in Europe between 2020 and 2021, which is still less than the ten-year average of 350 poor-quality bathing waters.

Some bathing waters are still of poor quality

In 2021, 332 or 1.5% of bathing water sites in the EU were of poor quality (Figure 3). While the share of poor-quality sites dropped slightly since 2013, problems persist at bathing waters of poor quality or bathing waters that are often affected by short-term pollution. It is imperative to assess the sources of pollution in their catchment area and implement integrated water management measures. At bathing sites for which the origins or causes of pollution are difficult to identify, special studies of pollution sources are needed.

In six EU countries, 3% or more of bathing waters were of poor quality: Estonia (two bathing waters or 3.1%), France (99 bathing waters or 3.0%), the Netherlands (34 bathing waters or 4.6%), Latvia (two bathing waters or 3.6%), Slovakia (one bathing water or 3.1%) and Sweden (16 bathing waters or 3.5%). In Albania, the number of poor bathing sites dropped significantly since 2015, when 31 bathing water sites (or 39.1%) were assessed as poor. In 2021, there were only eight poor bathing waters (or 6.7%) in Albania. This improvement can be linked to the construction of five wastewater treatment plants in Albania in recent years.

Swimming at bathing sites with poor water quality can result in illness. Bathing water sites classified as poor must be closed throughout the following bathing season and must have measures in place to reduce pollution and eliminate hazards to the health of bathers.

Management measures are primarily expected to be implemented at those bathing water sites where water quality is sufficient or poor. The Directive requires Member States to:

- Introduce adequate measures, including bathing prohibition or advice against bathing, with a view to preventing bathers' exposure to pollution;

- Identify the causes and sources of pollution, and reasons for the failure to achieve sufficient quality status;

- Take adequate measures to prevent, reduce or eliminate the causes of pollution such as implementation of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD) and a focus on reducing sewer overflows;

- Alert the public through a clear and simple warning sign, and inform them of the causes of the pollution and measures taken.

According to the Bathing Water Directive, bathing must be permanently prohibited or permanent advice against bathing put in place at bathing water sites that have been classified as poor for five consecutive years or more. In 2021, this was the case for 45 EU bathing waters: 31 in Italy, eight in France, two in the Netherlands, and one in Czechia, Estonia, Poland and Sweden respectively.

In 2020, 289 bathing water sites in the EU were of poor quality, while 201 of these remained poor in 2021. Of the 88 remaining bathing sites, 54 improved their water quality to at least sufficient between 2020 and 2021, while the remaining 34 bathing sites were either excluded from the monitoring programme or could not be assessed due to implemented measures, which might affect bathing water quality or the lack of a sufficient number of samples.

Monitoring and assessment of bathing water quality in Europe

During the bathing season, local and national authorities took bathing water samples and analysed them for the types of bacteria that indicate pollution from sewage and livestock breeding. Polluted water can have impacts on human health, causing stomach upsets and diarrhoea if swallowed. Based on the levels of bacteria detected, bathing water quality was then classified as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘sufficient’ or ‘poor’.

Member States establish their respective monitoring calendars, which must follow the provisions of Annex IV of the Bathing Water Directive:

- one pre-season sample is to be taken shortly before the start of the bathing season;

- no fewer than four samples (including the pre-season sample) are to be taken and analysed in the most recent season;

- an interval between sampling dates should not exceed one month.

If all three requirements are fulfilled, the monitoring calendar status is considered as ‘implemented’. In 2021, full monitoring requirements were implemented at 98% of European bathing waters, which is a higher share compared to the previous season, when the monitoring was affected by the pandemic measures. In Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Latvia, Malta and Slovenia the monitoring calendar was fully implemented at all reported bathing waters.

Review of the Bathing Water Directive

In the context of the European Green Deal and the Zero Pollution Action Plan, the European Commission is currently assessing whether the Bathing Water Directive is still fit for purpose in order to protect public health and improve water quality or if there is a need to improve the existing rules and propose relevant updates, including new parameters. During the review process stakeholders interested or directly involved in the implementation of the directive have been consulted via a number of activities, including two thematic workshops on evaluation and impact assessment as well as an open public consultation.

The Bathing Water Directive has not been analysed in isolation as its implementation is supported by a broad EU framework of water legislation, including the Water Framework Directive (WFD), the Environmental Quality Standards Directive (EQSD), the Groundwater Directive (GWD), the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) and the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD). The ongoing revision of the UWWTD looks, among other things, into ways of addressing remaining pollution from urban sources, including storm water overflows that have an impact on bathing water quality. The ongoing review of the EQSD and GWD explores options for revising the lists of chemical pollutants, in particular pollutants of emerging concern, in light of new scientific developments. The MSFD is undergoing an evaluation process to assess whether its objectives to maintain healthy, productive and resilient marine ecosystems, while securing a more sustainable use of marine resources, have been met.

Bathing waters in urban areas are supporting European Green Deal objectives

Of all European bathing waters, more than 1,800 are located in 193 cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants and are as such a valuable attribute of urban public spaces. Socio-economic and environmental benefits that stem from clean and safe urban bathing waters in Europe include public health, ecosystem services and recreation values, but also have numerous other values. One springs from the desire of urban citizens to live in eco-friendly cities, which increases the need to swim ‘in our own water’ and can be, as such, a symbol of a healthy aquatic environment. Some of the socio-economic and environmental benefits provided by urban bathing water sites are not immediately obvious. Such ‘invisible' benefits can be generated over wide geographic and long temporal scales and include social policy and planning, overall management of urban water resources, improved resilience to climate change and overall improvement of public space as well as quality of life.

Following decades of successful environmental legislation, such as the Bathing Water Directive, Water Framework Directive and Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive, we have improved the quality of water in many - but not all - urban areas. Key ongoing problems include:

- pollution loads reaching cities along rivers from upstream areas;

- rainwater overflows from city sewers during heavy rains;

- sudden surface runoff from paved urban areas;

- built-up water banks;

- narrowed riverbeds;

- insufficient riparian vegetation.

These issues are often exacerbated in multiple stressor ‘cocktails' due to ongoing climate change and habitat alterations. Many urban waters across Europe remain unsuitable for bathing because of excessive levels of pollutants posing public health risks. A number of EU strategies can help improve the situation. The recently adopted EU Strategy on adaptation to climate change sets out how the European Union can adapt to the unavoidable impacts of climate change and become climate resilient by 2050. In addition, the EU Biodiversity strategy for 2030 sets a plan to put Europe’s biodiversity on the path to recovery by 2030 for the benefit of people, the climate and the planet. Last but not least, the Zero Pollution Action Plan, a key deliverable of the European Green Deal, sets key 2030 targets to speed up pollution reduction at source, thus contributing to its 2050 vision to reduce pollution in water, air and soil to levels no longer considered harmful to health and natural ecosystems.

The European Topic Centre on Inland, Coastal and Marine Waters (ETC/ICM) is preparing a technical report on the synergies between the environmental, social and economic benefits of urban bathing water designation, and the goals of the European Green Deal to shift European economies towards a more sustainable future.

Find your local beach!

Member States are required by the BWD to use ‘appropriate media technologies, including the Internet’ to actively disseminate information. Today, countries maintain national or local websites with detailed information on each bathing water site. These websites generally include a map-search function and allow a user to see monitoring results, both in real time and for previous seasons.

At the European level, bathing water information is made available to the public through the EEA's bathing water web pages. Users can check bathing water quality on an interactive map, download data and individual country reports, explore details through a link to the national online bathing water profile and make comparisons with previous years.

References

EC, 2006. Directive 2006/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 February 2006 concerning the management of bathing water quality and repealing Directive 76\160\EEC, OJ L 64, 4.3.2006, pp. 37-51.

EEA, 2017. Urban Waste Water Treatment (Online). Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/urban-waste-water-treatment/urban-waste-water-treatment-assessment-4 Accessed 26 April 2020.

EEA, 2021. Bathing water management in Europe: Successes and challenges, EEA Report, 11/2020, European Environment Agency. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/bathing-water-quality-2020.

Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive 91/271/EEC of 21 May 1991 of the Council concerning urban waste-water treatment OJ L 135, 30/05/1991 P. 0040 - 0052.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 08/2022

Title: European bathing water quality in 2021

EN HTML: TH-AM-22-008-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-474-7 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/0952

EN PDF: TH-AM-22-008-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-475-4 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/005778

This briefing presents data from 2021 when the United Kingdom was not an EU and EEA Member State anymore and is therefore not reporting bathing water quality data to the EEA.

Notes: * If a bathing water site was newly identified during the last assessment period and before the complete four-year dataset of 2019-2021 could be collected - i.e. identified not earlier than 2019 - it is counted as “newly identified”; this is also true if enough samples were collected in a shorter period. ** If a bathing water site was subject to changes described in BWD Article 4.4.b within the last assessment period, it is assigned management status “Quality changes”. Such status is assigned until the complete four - year dataset of samples taken after changes took effect is available.

Document Actions

Share with others