The war in Ukraine, and its consequences for global and especially EU energy supply, and the worsening impacts of climate change have dominated this year’s news headlines across the world. We have read about volatility in global energy prices, concerns about energy shortages in winter, and record droughts affecting agricultural production at a time when food prices were already rising.

These issues are connected. If we could replace fossil fuels with abundant renewable energy, we would cut energy prices, reduce emissions and lower the future risks of climate change, including the impact on food production.

Moving away from fossil past

Fossil fuels, such as oil, gas and coal, are made of decomposed plants and animal residues that have been transformed into their current forms over millions of years in the Earth’s crust and its layers. Fossil fuels contain chemical energy, which is released along with various pollutants when burned.

Compared with electricity, which can be generated from renewable sources, such as solar and wind power, but which is rather difficult to store, fossil fuels are easier to store and transport to end-users. The energy infrastructure and technology developed since the Industrial Revolution has been largely based on the use of fossil fuels.

In recent years, EU policies have set ambitious targets to accelerate the shift towards sustainable energy. And these have started bearing fruit, with a growing share of Europe’s energy needs being met through renewable energy sources.

In 2021, more than 22% of the gross final energy consumed in the EU came from renewables. However, the share of renewables in the energy mix varies substantially across the EU: in Sweden it is about 60%; in Denmark, Estonia, Finland and Latvia more than 40%; and in Belgium, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands between 10% and 15%.

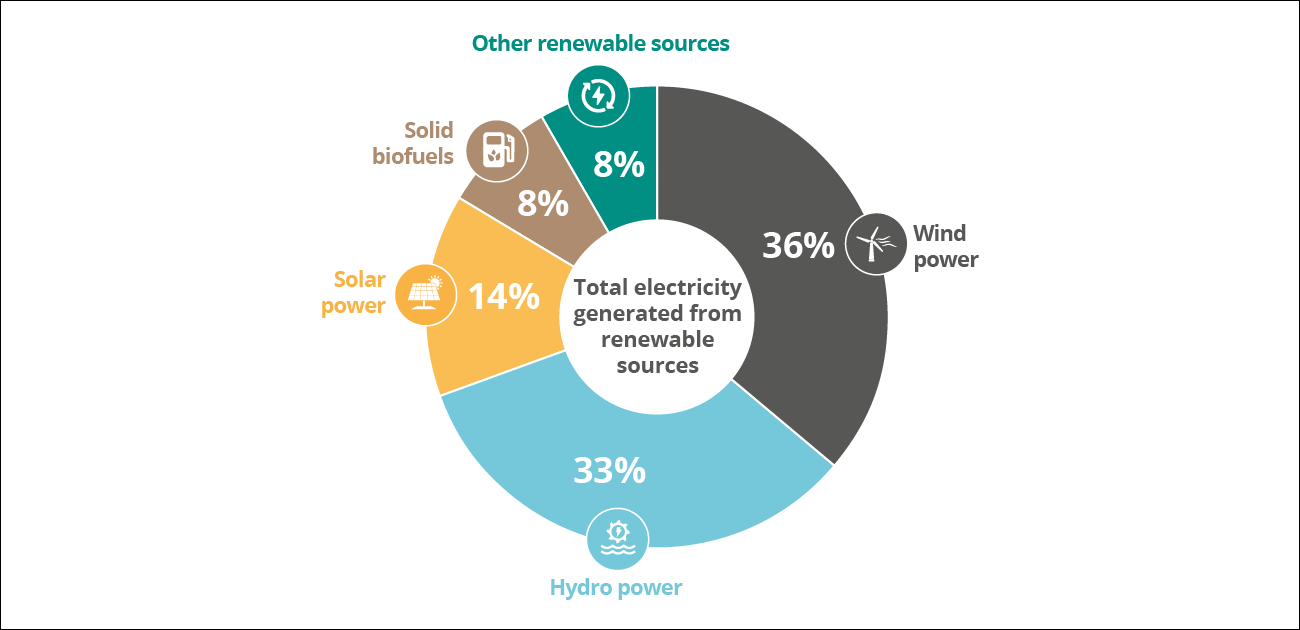

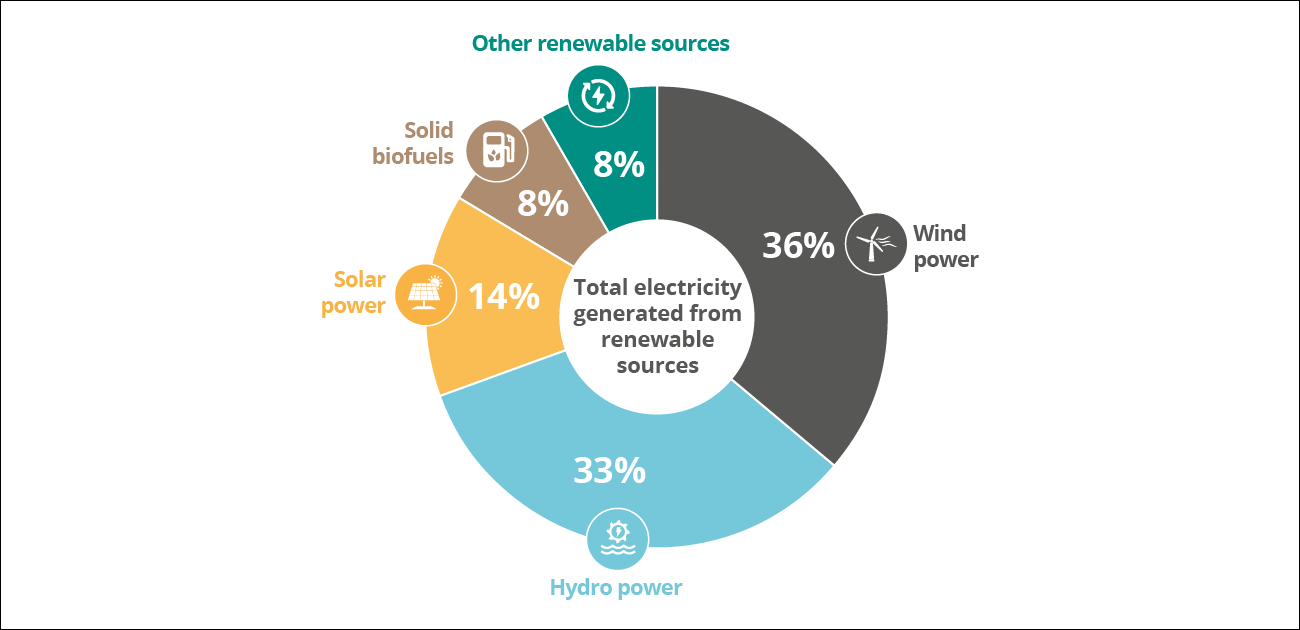

According to Eurostat data, wind and hydro power together accounted for more than two thirds of the total electricity generated from renewable sources (36% and 33%, respectively) in the EU in 2020. The remaining one third was from solar power (14%), solid biofuels (8%) and other renewable sources (8%).

Source: Eurostat.

Endless renewable energy potential but …

Natural sources — such as solar, wind, tidal and geothermal — have the potential to create far more energy than the world currently needs. Yet, this potential does not match what we can currently achieve. One challenge is to set up enough capacity to capture the energy of, for example, sunlight or wind and convert it to a usable format, such as electricity. Another challenge is to be able transport the energy to where it is needed or store it for later use.

A future energy system needs to be resilient and adaptable to the inevitable impacts of climate change, such as droughts, heatwaves and storms. As the share of wind and solar power increases, the system also needs to be flexible enough to function well even when the wind does not blow or the sun does not shine.

A flexible power system can ensure a steady supply of energy and reduce peak demand. Apart from ensuring diversity in energy sources, the system can be improved, for example, by improving energy storage, smart integration of heating, transport and industry sectors, or addressing peaks in demand through dynamic pricing or smart grids and appliances.

Source: EEA’s Climate and Energy in the EU portal.

Wind and solar projects across Europe

Many recent projects around Europe are beginning to demonstrate the tremendous potential of renewable energy. In August 2022, in Spain, Iberdrola turned on the largest solar power plant in Europe with about 1.5 million solar panels and a capacity of 590 megawatts that will produce enough electricity to supply more than 330,000 households.

The 49 wind turbines in the Danish offshore wind farm Horns Reef 3 have a total capacity of 407 megawatts and are estimated to meet the annual electricity consumption of approximately 425,000 Danish households.

Portugal is installing Europe’s largest floating solar park on the Alqueva reservoir, consisting of 12,000 panels. In April, Greece inaugurated a 204 megawatt solar farm with bifacial panels, which can collect light on both sides.

The REPowerEU plan to accelerate the transition to renewable energy and reduce dependency on Russian fossil fuels aims to boost such projects. The EU solar energy strategy is set to double solar power capacity by 2025 and the European solar rooftops initiative would introduce an obligation to install solar panels on larger public and commercial buildings and gradually also on new residential buildings. The process of obtaining permits for major renewable projects should also become faster.

What about the grid? And storage?

The challenge of shifting to renewable sources of energy is not only production capacity. Power plants need to be connected to a grid that can accommodate the growing production capacity and bring it to end users.

To ensure a reliable power supply, promote the uptake of renewables and reduce the costs of electricity transmission, some regions have been encouraging, for example, homeowners or businesses to become producer-consumers — prosumers — generating electricity with solar panels, consuming a share of it and feeding the excess power to the grid.

A recently published EEA report finds that European prosumers already have many opportunities that can bring benefits for their own households, as well as society. By investing in energy production or storage, prosumers can make savings in their own energy costs, speed up Europe’s energy transition and reduce greenhouse emissions. Moreover, these opportunities can be expected to increase in the coming years with better and cheaper technology and with new policies.

Many electricity suppliers have also started encouraging households to adjust their energy consumption to match production levels. This is possible with dynamic pricing that depends on the time of the day and varies from hour to hour. In times of excess production, consumers can get almost free electricity that can be used, for example, to charge electric cars.

Clean energy in a circular economy

Manufacturing more solar panels or wind turbines also raises some difficult questions: can we get enough of the minerals used in solar panels or wind turbines? Where can we install wind farms? How do these power plants affect wildlife? And how do we ensure that the resources, such as rare Earth minerals, used in their production remain available?

The EEA’s analysis has shown that the growth in renewables has reduced many global environmental and climate pressures, and that targeted actions can help minimise some adverse effects, such as freshwater ecotoxicity and land occupation. With a growing number of renewable projects on the way, assessing the trade-offs with habitats and ecosystems will be essential.

The Energy and Industry Geography Lab, developed by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission, is a new tool to address some of these concerns. The Lab can be used to identify the most suitable ‘go-to areas’ for wind and solar projects, for example sites avoiding protected areas or known bird migratory routes.

Boosting the clean electricity supply requires a growing generation capacity and adjustments in the infrastructure. It means more solar panels and more wind turbines on the supply side, as well as a better connected smart grid and — vitally — smart users who pay attention to energy efficiency. Whatever decisions we make need to factor in these long-term sustainability considerations.

Text box: Making sure no one is left behind

Europe needs a rapid and fundamental change in its systems of production and consumption. This transition towards sustainability affects different people in different ways. It is therefore critical that we ensure a fair transition and that those who are most vulnerable are not left behind.

An EEA analysis has shown that Europe’s most vulnerable citizens are disproportionately affected by air pollution, noise and extreme temperatures. According to another EEA study on ‘just resilience’, vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, children, low-income groups and people with health problems or disabilities are the most affected by climate change. In addition, adaptation responses to climate may worsen existing inequalities or even create new ones.

Europe needs to improve its energy efficiency and cut its dependency on fossil fuels. However, all Europeans do not have the same opportunities to install heat pumps, renovate their homes or buy new electric cars. In remote areas, public transport is often scarce. Energy poverty can mean not being able to keep warm during winter.

The EEA study on ‘just resilience’ highlights that making sure that the most vulnerable groups are not left behind requires measures that benefit those groups specifically. For example, investments in green spaces can be made in locations that need them the most during heatwaves or for flood protection. Moreover, the most vulnerable should not be excessively affected by the burdens of adapting to climate change.

The EU ‘Just Transition Mechanism’ aims to mobilise around EUR 55 billion over the period 2021-2027 in the most affected regions to alleviate the socio-economic impact of the sustainability transition outlined in the European Green Deal.

The proposed EU Social Climate Fund aims to address the social impacts of extending emissions trading to the building and road transport sectors. The fund would provide direct support to vulnerable households as well as support for investments that reduce emissions in those two sectors.

Over time, Europe’s transition to sustainability is also about intergenerational justice, or fairness between current and future generations. By improving the long-term outlook for Europe’s economy, environment, climate and social cohesion, the actions that are taken now aim to create a better future for the generations to come. This intergenerational responsibility is also a guiding principle of the EU Eighth Environment Action Programme.

Document Actions

Share with others