|

European Packaging Waste Trends

and the Role of Economic Instruments

European Voice conference

PACKAGING OUR FUTURES

Brussels, 1-2 March 2004

Professor Jacqueline McGlade

Executive Director, European Environment

Agency

|

View the PDF version of the speech. ( 293

Kb) 293

Kb)

|

|

Timing

|

Mr. Chairman,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a pleasure for me to be here today to speak about "European

packaging waste trends and the role of economic instruments" from the

perspective of the European Environment Agency in Copenhagen.

I would like to thank European Voice for inviting me, and

also to congratulate them on the timeliness of this conference.

The amended Packaging Waste Directive has just been adopted, and

work is under way to develop EU thematic strategies on waste prevention

and recycling as well as on the sustainable use and management of

natural resources.

So it seems a very good moment to reflect on what worked well in the

past, what perhaps did not work so well, and what our options are for

the future.

|

| EEA role |

By way of introduction, let me say a few words about the changing

role of the European Environment Agency in the European policy

process.

The Agency began work 10 years ago with the purpose of providing the

Community and the Member States with information on the state of the

environment in Europe, and trends in it, so that they have a sound

basis for policy action

Our membership has steadily expanded. Having been the first EU body

to take in all the acceding and candidate states, today we have 31

member countries.

|

| Policy effectiveness |

Increasingly the Agency has been asked by the European

Parliament, the European Commission and our member countries to report

and advise not only on the state of the environment but also on the

effectiveness of environmental policies and their implementation.

|

| EEA Strategy 2004-2008 |

We have responded by including this as an important new area of work

in our strategy for 2004-2008.

|

|

Packaging waste

|

One of our priority areas for the next five years is the sustainable

use and management of natural resources and waste.

Packaging waste is of particular interest. It is a major and growing

waste stream. The Packaging Waste Directive has been in place for a

decade and stakeholders are now taking stock. And from the point of

view of evaluating policy effectiveness, the Directive is especially

interesting because it is one of the few pieces of legislation that

contain directly measurable quantitative targets.

These are among the reasons why the Agency has chosen packaging

waste as one of the first areas of policy we will assess for its

effectiveness. I will come back to this later.

|

| Three main points |

I would like to highlight three points that I think are

particularly important for the debate on packaging waste.

|

|

First point

Packaging waste amounts have increased

|

The first is that:

Packaging waste amounts have increased in most European countries

despite the agreed objective of waste prevention. This is both

problematic and worrying from an environmental perspective

Let me illustrate this with a graphic.

|

| |

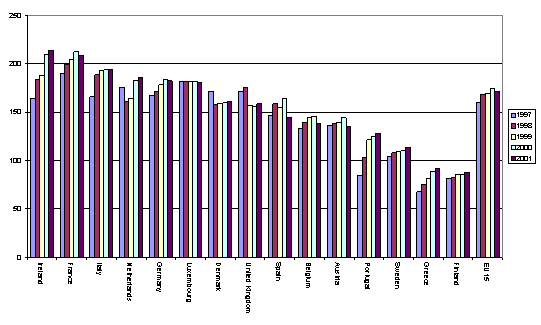

Slide 1: Packaging waste generation in EU 15 (kg per

capita) |

|

|

|

Big differences in EU countries

Amounts are increasing

|

As you can see, there are big differences in the amounts of

packaging waste EU countries generate. The levels range from under 100

kg per capita per year in Greece and Finland to over 200 kg in Ireland

and France. Some of this difference can be explained by differences in

the definitions of what constitutes packaging and packaging waste.

As you can also see, the amount of packaging waste is increasing in

the EU. Between 1997 and 2001 it grew in 10 of the 15 EU countries. In

the EU as a whole, the amount increased by 7% over the period.

For me it is difficult to draw any other conclusion from this than

that the EU and most Member States have so far failed to meet the waste

prevention objective of the Packaging Waste Directive.

|

| Trend to continue? |

Unfortunately it looks like this upwards trend is set

to continue.

|

| |

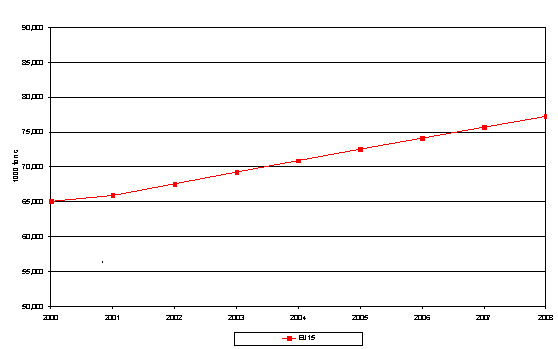

Slide 2: EEA projections of packaging waste in EU15 in

a business as usual scenario (1000 tons). |

|

|

| Packaging waste projections |

The EEA has used econometric modelling tools to project packaging

waste amounts for the near future. These projections show that,

assuming continued growth in production, the amount of packaging waste

could increase by 18% from 65 million tonnes in 2000 to 77 million

tonnes in 2008. This is under a business as usual scenario.

Of course, the introduction of additional policy measures could

prevent this scenario from being realised. Much will depend on the

measures countries put in place to implement the amended

Directive.

|

| Why are amounts increasing? |

What is behind this increase?

The general answer is that the generation of packaging waste is

closely related to production and consumption in society. That is why

the big challenge is to put in place policies that are effective in

decoupling waste generation from growth.

A more specific factor is that a large percentage of packaging waste

is related to the consumption of food, which is continuing to increase

in Europe. Consumers want larger amounts of imported and pre-prepared

foods, which often require more packaging. At the same time, household

sizes are decreasing. The larger number of households also means that

we generate more packaging waste.

|

| Problematic and worrying |

This increasing trend is a cause for concern because the generation

of waste always has environmental impacts and represents a loss to

society of materials and energy.

Studies show that recycling generally creates less impact than

disposal, but all waste management methods do have impacts.

And the environmental impacts from packaging occur not only in the

management of the waste, but also in the production, transport and use

phases of the packaging itself.

They can include, for example:

- emissions of air pollutants and greenhouse gases;

- use of fresh water and discharges of waste water, which if not

properly treated can cause pollution;

- the depletion of non-renewable natural resources and the damage

sometimes associated with their extraction; and

- using up limited space in landfills, whose own impacts on the

surrounding environment may or may not be properly managed.

|

| Second point |

My second point is very much linked to the first.

The successful achievement of recycling and recovery targets is good

news for the environment. But it is important at the same time to

address both the broader objective of waste prevention and the marginal

economic costs of achieving high recycling rates.

|

|

Target achievement

Recovery

Recycling

|

If one looks at country performance in meeting the recovery and

recycling targets of the 1994 Packaging Waste Directive, the picture

looks very good in terms of target achievement.

For recovery, almost all EU countries met the minimum 50% recovery

target in 2001, and seven countries have already met the 60% target to

be achieved by 2008. Acceding countries are also achieving significant

progress.

For recycling, the picture in 2001 looked like this:

|

| |

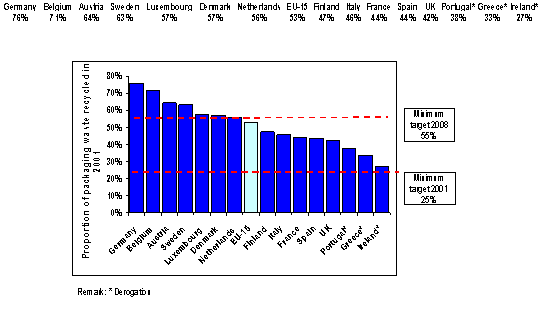

Slide 3: Recycling of packaging waste in EU15 in

2001 |

|

|

| |

All EU countries met the target of minimum 25%

recycling by 2001. In fact, seven countries have already met the 2008

target of 55% recycling.

|

|

Narrow focus?

Environmental perspective

Economic perspective

|

This is indeed very good performance in terms of target achievement

- and it is good news for the environment.

But to me it raises an important question. Are countries and

stakeholders focusing narrowly on reaching the recycling and recovery

targets at the expense of waste prevention and economic efficiency?

Achieving recycling and recovery targets results in lower

environmental impacts from the waste.

But meeting waste targets does not diminish the environmental

impacts of the manufacturing, transport and use of packaging materials.

So it is very important not to lose sight of the waste prevention

objective.

From an economic perspective, the marginal economic cost of

increasing recycling is generally higher the more is recycled already.

Therefore, at some stage countries may reach a point where recycling

becomes economically inefficient compared to other solutions.

A question that may need to be addressed at some time in the future

is whether it might be better for the environment and the economy to

focus on recycling targets for materials rather than for

packaging.

|

| Third point |

This leads me to my third main point, which is as follows:

Economic instruments have an overall efficiency advantage for

society as they can achieve environmental objectives and targets at

relatively low cost. Overall, a mix of policy instruments seems to be

the most effective means to reduce the environmental impacts of

packaging.

|

|

Questions in conference programme

Question 1

|

I would like to expand on this point by addressing the three

questions about economic instruments asked in the conference

programme.

The first question is "How far are the marginal environmental

burdens imposed by packaging already covered by recovery organisation

fees and other costs of compliance with regulations?"

|

|

Polluter Pays Principle

Getting the prices right

Economic instruments

Regulation

Preference for market based approaches

Marginal costs

Life-cycle analysis

|

This question covers several important points.

As you know, a major objective of EU and national environmental

policies is the Polluter Pays Principle. This means that polluters

should pay for the costs they cause to society.

Economic activities such as producing, transporting and disposing of

packaging cause environmental impacts that generate costs and loss of

welfare that are not paid for by the polluters.

These external environmental costs should be included in the costs

of activities and their market prices in order to "get the prices

right". If the prices are right, the market will sort out the demand

for the polluting products and for non- or less-polluting

alternatives.

An efficient way to include these external costs is to use economic

instruments, such as taxes, deposit-refund systems and tradable permit

systems. Economic theory says that it is most efficient not to cover

the average environmental costs but the marginal ones - in other words

the extra costs caused by an additional unit of environmental

burden.

Applying economic instruments is not the only way to internalise

costs, of course. Regulations that prescribe environmental improvements

- for example reducing the weight of glass bottles or improving

disposal methods - also reduce environmental costs, while the polluters

bear the costs of these measures in line with the Polluter Pays

Principle.

There is, however, a large degree of academic consensus on the

preference for market-based approaches that in general lead to more

efficient solutions. The basic argument is that environmental impacts

get reduced where the marginal costs are lowest.

Answering question 1 would require precise knowledge of what the

marginal environmental costs are.

A certain amount of knowledge exists but its precision is often

disputed. A common assessment method is life-cycle analysis but its

findings, and the methodologies used, tend to be contentious. Moreover,

marginal costs are not constant, but differ from situation to

situation.

For example, the environmental costs of an empty one-way bottle

dumped on a landfill in a densely populated area are higher than the

costs of exactly the same bottle thrown on a landfill in a sparsely

populated area.

So the first question is hard - if not impossible - to answer. It is

important to note, however, that in practice not only environmental and

compliance costs count, but also the costs of legislation,

implementation, enforcement and monitoring.

|

|

Question 2

Tautology

Second best solution

Complying with targets

Criteria

|

The second question is: "If the internalisation of external costs

does not affect prices sufficiently to change companies' or consumers'

behaviour, should further economic instruments be applied - and if so,

what criteria should be used to judge whether these measures are fair

or proportionate?"

The way the question is posed a bit of a tautology. Assuming perfect

knowledge, full internalisation of external costs does not require any

additional change in behaviour. If society is still unhappy with the

outcome, it means that external costs are higher than originally

estimated, and internalisation has been only partial.

Of course, this is theory, but it indicates an important point.

Ideally, we aim at full internalisation, but too little is known about

environmental costs. So a second-best solution has been chosen, in the

form of the objectives and targets set out in the Packaging Waste

Directive.

We assume that these objectives and targets represent the optimal

balance between compliance costs and remaining environmental damage -

optimal in the sense that the costs of any further measures would be

greater than the damage prevented.

Although the main function of economic instruments is to internalise

environmental costs, in practice they are used to get actors to comply

with the targets.

If the targets are not met, instruments should be strengthened, and

the question of whether or not environmental costs are fully

internalised is less relevant. Of course, the question of whether or

not the targets represent the optimum for society is still very

relevant.

Any measures taken should be judged against the criteria of fairness

and proportionality. Instruments should be effective, flexible and low

in administration costs. Economic instruments are increasingly seen as

good performers in this respect.

The most recent addition to the set of EU policy and measures to

control greenhouse gas emissions is the flexible mechanisms, which are

good examples of economic instruments and include the first system of

tradable permits introduced at the EU level. A breakthrough of a

kind!

|

|

Question 3

Tradable permits in the UK

Increased recovery

Criticism

Time to study

|

This brings me to the programme's third question, about the

potential benefits of the UK's Packaging Recovery Note or PRN

approach.

This is a tradable permit system working as part of a policy mix

which also includes legal requirements for municipalities and a

landfill tax.

Would it be worth considering a tradable permit system for packaging

waste in other EU countries or in the EU as a whole?

The PRN system is still relatively new and I think the answer has to

be that it is too early to say yet.

What is clear is that with the help of the PRN system the recovery

rate for packaging waste in the UK increased from 27% in 1997 to 48% in

2001. In addition, the direct costs of the system are relatively

low.

On the other hand one could also say that the PRN system fell just

short of enabling the UK to meet the minimum recovery target of 50% set

by the directive. I'm aware that there have been a number of other

criticisms too.

So I would say the jury is still out on the PRN system. It is

definitely an interesting and innovative approach but its effectiveness

needs further study before one can judge the potential for applying it

more widely alongside other EU or national initiatives.

|

|

The packaging sector's perspective

Distorting the market

Differences of view are understandable

Forthcoming Communication

|

What I have said so far is largely seen from the point of view of

the environment and the efficiency of policy mixes at macro-economic

level. But how does it look from the packaging sector's

perspective?

The packaging sector is confronted not so much with the Packaging

Waste Directive itself as with the various different ways in which

national authorities have implemented it.

Some Member States comply with the targets, some have set their own

higher targets, and some have derogations.

Some apply taxes or charges on packaging, some have (mandatory)

deposit systems, and an increasing number of Member States apply

landfill and incineration taxes. Some arrange agreements with relevant

parties.

All these approaches have various costs for the packaging

sector.

Distorting the market by creating trade barriers or causing unfair

competition is a major argument used by representative bodies in the

packaging industry, and by the Commission, against some existing or

planned economic instruments, in particular deposits.

Yet correcting market distortions is the very reason for

implementing economic instruments in the first place, as they are a

straightforward way of internalising external costs and hence of

"getting the prices right".

These differences of appreciation are understandable, and perhaps

inevitable.

Industry sectors obviously prefer not to incur the additional costs

that can result from policy measures, even when these measures may be

beneficial to society as a whole.

For their part, Member States don't always think the same way

because they have different economic structures and interests, and

different levels of environmental ambition.

Comparing the environmental burdens of one-way and reusable

packaging, and trying to agree on the results, seems to be one of those

issues where these differences come to the forefront!

The forthcoming Communication on the use of market-based instruments

in the internal market may help to find more common ground.

|

| Database on economic instruments |

Before I finish on economic instruments, let me just mention that

the European Environment Agency and the OECD together maintain a

database of economic instruments used in Europe.The database is freely

available through our website.

It shows, for example, that in 2001:

- Fifteen countries in Europe applied a tax or charge on packaging

items;

- Thirteen countries had deposit-refund systems in place, although

this information may not be complete;

- Seventeen countries applied taxes on waste disposal and/or

incineration; and

- Six countries concluded covenants with relevant partners on

packaging and packaging waste.

|

|

Policy effectiveness

Austria

Objectives and targets met

Cost-effectiveness

The packaging waste directive

Other countries

Mix of instruments

|

As I said earlier, packaging waste is one of the first areas of

policy that the EEA is assessing for its effectiveness.

We are currently looking into the effectiveness of packaging waste

management systems in five EU countries: Austria, Denmark, Ireland,

Italy and the United Kingdom. The study is not finalised yet, but we do

have some initial insights.

One example is the Austrian packaging waste management system, which

combines a mandatory producer responsibility scheme with an array of

economic instruments. The results seem to be impressive from an

environmental perspective.

The prevention objective has been met as a result mainly of the ARA

producer responsibility scheme. Recovery and recycling targets have

been achieved and exceeded as a result of the producer responsibility

scheme, the landfill tax and the landfill ban.

At the same time, financial indicators show a continuous improvement

of the cost-effectiveness of the Austrian packaging waste system.

As the Austrian waste management system was in place before the

Packaging Waste Directive and before Austria joined the EU, the

Directive does not seem to have had a major effect on packaging waste

management in Austria.

For other countries, for example Italy and the UK, the Packaging

Waste Directive does indeed seem to have had a significant effect on

the waste management systems put in place.

The five countries have very different packaging waste management

systems, but one general conclusion can be drawn from the exercise:

Countries that have put in place a mix of instruments seem to have

been most effective in meeting their objectives and targets.

|

| To conclude |

This leads me back to my three main points. Let me conclude by going

over them once again.

Firstly, the amount of packaging waste has increased in most

European countries despite the agreed objective of waste prevention.

This is a cause for concern from an environmental perspective.

Secondly, the successful achievement of recycling and recovery

targets is good news for the environment. But it is important at the

same time to address both the broader objective of waste prevention and

the marginal economic costs of achieving high recycling rates.

Thirdly, economic instruments have the advantage of being more

efficient for society as they can achieve environmental objectives and

targets at relatively low costs. Some economic instruments can generate

additional costs for the packaging industry, but these costs can be

reduced when common approaches are chosen in Europe. Tradable permits

for packaging waste seem to have potential but it is too early to judge

their effectiveness. Overall, a mix of policy instruments seems to be

the most effective means to reduce the environmental impacts of

packaging.

Thank you for your attention.

|

Document Actions

Share with others