Surface waters

Finland is rich in

surface waters, with a total of 187 888 lakes and ponds larger than 500

square metres, and rivers totalling 25 000 kilometres in length. Almost a

tenth of the country‘s land area is covered by water. Finland’s lakes contain only

235 cubic kilometers of water (Main characteristics of the surface waters in

Finland). Finland’s shallow lakes are easily contaminated by

pollution. Even relatively low concentrations of excess nutrients, acidic

deposition or other harmful contaminants can easily disrupt their sensitive

aquatic ecosystems.

Discharges of

harmful substances into Finland’s inland and coastal waters have fallen

considerably during the last few decades.

The monitoring and state of

surface waters

The monitoring is

composed of both administrative monitoring and compulsory inspections by

industrial operators and other businesses. The frequency of water quality

observations and the factors under analysis vary according to local needs.

Biological monitoring has been expanded, and the process will continue over the

coming years.

Ecological and chemical

state of surface waters

Most of Finland’s

classified water bodies are in a high

or good ecological state. Waters with lower ecological status than ‘good’

include almost a third of the classified lakes, half of the classified

stretches of rivers, and more than half of the total extent of coastal waters. With

a few exceptions, the chemical state of the water is good.

New classification system

for the surface waters

The classification

in 2008 was carried out to meet the obligations under the EU Water Framework

Directive and related national legislation. A target has been set that all

surface waters should have a good or excellent ecological status by 2015, and

conditions in waters already classed as good or excellent should not

deteriorate.

The amount of work

needed to achieve the goal of a good ecological status is greatest for rivers

and coastal waters. Particularly in southern, western and southwestern Finland,

many rivers are still only in a poor or passable state. Problems include

diffuse loads of nutrients from farmland, and constructions such as dams along

watercourses. In northern Finland, most rivers are in an excellent or good state.

Currently, the ecological quality

status of most of Finland’s inland waters is either good or high. However, the

quality of over 40% of total river length and 60% of the coastal water areas

included in the plans is moderate, poor or bad. The water quality of Finland’s

lakes is generally better. Only 2% of the groundwater resources important to

and suitable for water supply purposes are classified as bad, even though

approximately 500 groundwater areas are at significant risk from human

activity.

The status of lakes

is worst for small and medium-sized lakes in agricultural areas, where problems

associated with eutrophication, such as algal blooms, are widespread.

·

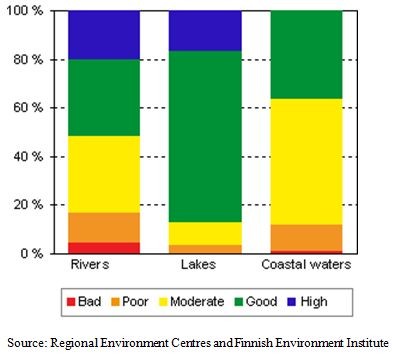

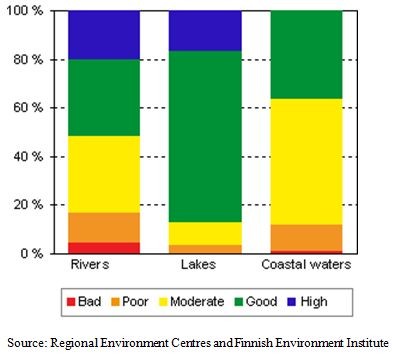

Table 1: Ecological status of surface waters by proportion of

total length (rivers) or surface area

Ecological status

|

Rivers

|

Lakes

|

Coastal waters

|

|

High or good

|

52%

|

87%

|

36%

|

|

Moderate, poor or bad

|

48%

|

13%

|

64%

|

Figure 1: Ecological

status of surface waters by proportion of total length (rivers) or surface area

Link to a more

detailed figure:

Ecological

status of surface waters assessed by river length and surface area of lakes and

coastal waters

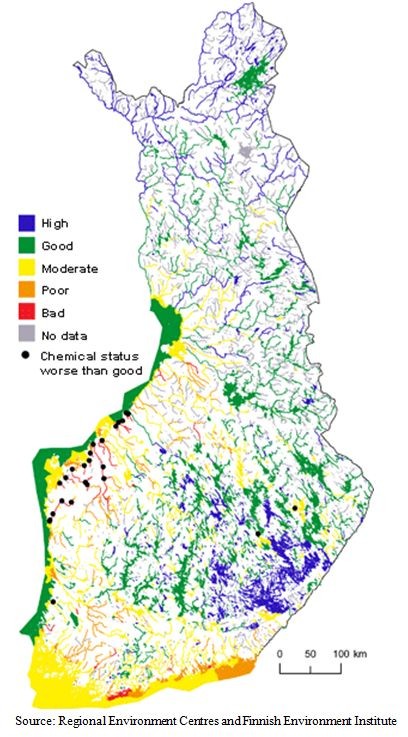

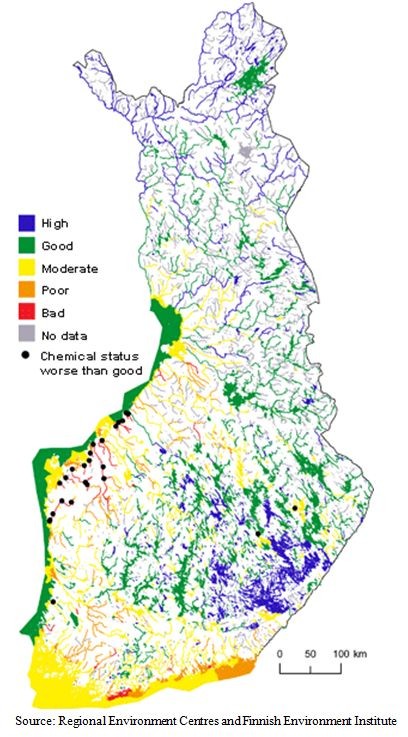

Map of the ecological state

of Finland’s surface waters

A provisional map

of the ecological state of Finland’s surface waters has been completed. Water bodies

are classified largely according to monitoring data mainly compiled over the

period 2000–2007.

Map 1: the ecological

status of the surface waters

Link to a

more detailed map:

Ecological

state of surface waters

See also:

Chemical status of surface waters

The chemical state

of surface waters is classified on the basis of environmental quality norms

defined for 42 harmful or hazardous substance and substance groups. The norms,

which refer to annual average concentrations of the substances in aquatic

environments, were included in Government Decree 1022/2006 on Substances

Dangerous and Harmful to the Aquatic Environment. Some of the norms applied in

evaluating the chemical state of water bodies have not yet been fully enacted

in official legislation, but they still serve as useful guidelines in the

classification procedure.

The concentrations

of harmful and hazardous substances measured in Finland’s surface waters have

generally been below the provisionally defined norms (environmental quality

standards), and in many cases the substances have not been detected at all.

Chemical statuses worse than “good” have been assigned to several rivers in

Ostrobothnia which flow through regions with acidic, sulphate-rich soils, and

contain high concentrations of substances including cadmium. Some of the metals

that affect the chemical state of water bodies also occur naturally, and this

factor must be considered in classifications to ensure that statuses are not

misleadingly lowered by naturally high concentrations of metals.

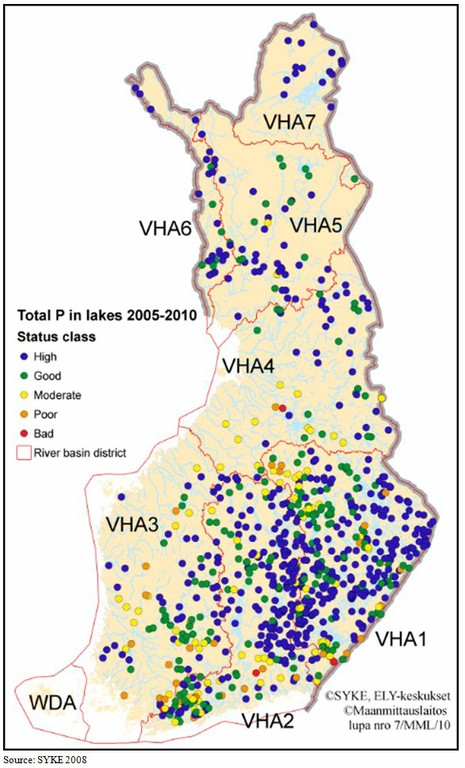

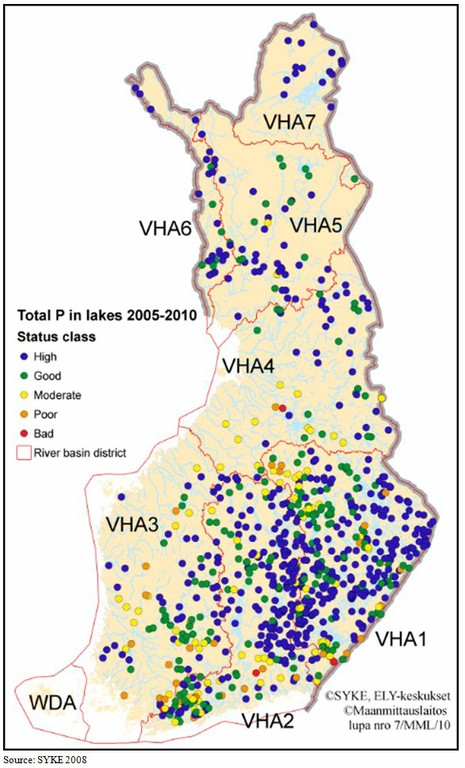

Map 2:

Finnish lakes classified by total phosphorus levels (median in 2005-2010).

Total P levels were compared to status class boundaries of total p in different

lake types.

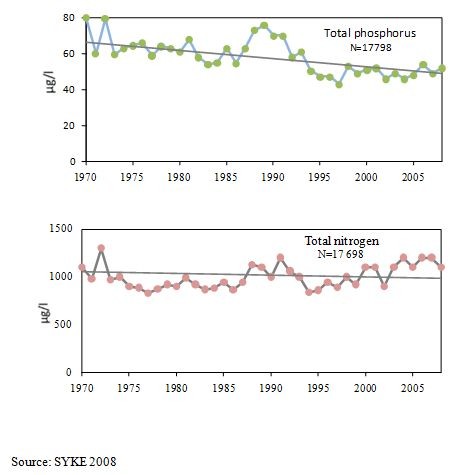

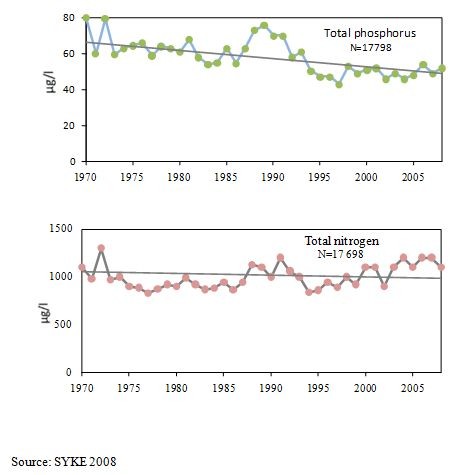

Figure 2: Annual

medians of total phosphorus and total nitrogen in 1970-2008 calculated for a

group of 33 Finnish rivers. Linear trend line is shown.

The earlier general usability classification

The general

usability classification of water bodies gives an idea about the average

suitability of the water bodies for water supply, fishing and recreation in

Finland. The quality class is determined based on the natural quality of the

water and human impacts. The water bodies have been classified as: excellent,

good, satisfactory, passable and poor (Criteria for the general water quality

classification in Finland).

The latest

classification was based on data from the period 2000–2003. It covered 82 %

of the total area of lakes larger than one square kilometre, 16 % of the

total length of rivers more than two metres wide as well as the sea area inside

the Finnish territorial waters.

The quality of

water was excellent or good in 80 % of the classified lake area. In

general, the water quality in rivers was worse than in lakes, because human

activities, such as agriculture and development, are concentrated along rivers.

Moreover, many rivers are sensitive to the effects of nutrient loading because

of their low flow rates. The quality in 43 % of rivers is classified as

excellent or good. These rivers are mostly located in northern Finland (Map of water quality of lakes, rivers, and sea

areas in 2000-2003), (Comparison of classifications in 1984-2003).

Water quality affected by diffuse loading

In the vicinity of

towns and industrial plants, water quality had improved considerably already at

the beginning of the 1990s, because of long-term measures for water protection.

These measures were further improved during the 1990s. However, a similar

improvement in the state of water bodies has not been observed in areas with

heavy diffuse loads.

See also: Large

lakes in good condition; problems in rivers and coastal waters

Acidification

Acidification problems

first became evident in the 1960s. It took some time for action to be taken, and

ultimately international agreements were signed to curb harmful emissions. The

concentrations of sulphur compounds declined and buffering capacity increased

in all types of lakes in Finland during the 1990s. Some 5 000 smaller

lakes in Finland are now considered to be recovering well from serious

acidification problems.

Declining

atmospheric deposition has also reduced acidification problems in Finland’s

groundwater reserves, although it may take decades for groundwater to recover

completely.

Eutrophication

In water bodies,

eutrophication particularly boosts the growth of planktonic algae. Its effects

can be seen in reduced water clarity and the increased growth of filamentous

algae and aquatic plants. In the worst cases, eutrophication may result in the

increased occurrence of massive blue-green algal blooms, oxygen depletion in

winter, and in dramatic changes in fish stocks.

Eutrophication is

basically a natural phenomenon. Certain lakes or habitats are naturally poorer

in nutrients than others are, but over time they may become richer in nutrients

through natural processes. Where nutrient pollution is widespread, however,

eutrophication often becomes a problem.

Badly affected

lakes can be restored to some extent by removing nutrients from the ecosystem

through selective fishing or the removal of excess plant growth. The

nutrient-rich silt on lake-beds may also be dredged or covered over. During the

winter, air may also be pumped into lakes to improve the oxygen content of

their deeper waters and slow the release of nutrients from bottom sediments.

See

also:

Toxic substances

Information on

concentrations of toxic substances is mainly limited to major point sources of

emissions, such as large industrial plants. Municipal wastewater treatment

plants, for instance, routinely measure only variables linked to eutrophication

and heavy metal concentrations in their treated effluent and sludge. Calculations

and extrapolation are also used to estimate the point loads and diffuse loads.

EU legislation and

Finland’s other international commitments mean that in future, environmental

loads of hazardous substances must be monitored much more widely than they have

been so far.

Groundwater

Finland’s

groundwater reserves are replenished in the spring when the winter snow and ice

melts, and often again in the autumn – typically the rainiest season.

Although Finland

has plenty of aquifers – a bit over 6 000 – these resources are not

distributed evenly across the country. Water is typically clean, well

oxygenated, and often also easily extractable. Especially the Salpausselkä

deposits in southern Finland hold important aquifers.

Groundwater can be

found in almost every part of Finland, but is particularly widespread in areas

with extensive deposits of permeable sands and gravels formed during the last

ice age. The depth of the water table may vary from less than a metre to more

than thirty metres, but is typically about two to five metres below ground

level.

Groundwater

reserves can be significantly reduced, and the water table lowered, due to the

excessive use of groundwater, or after major groundwork or excavation, as well

as following droughts.

In Finland,

groundwater is widely used by local residents and by waterworks, since it is

often much purer and better protected from contamination than the water in

lakes and rivers. Groundwater can usually be consumed safely without any

treatment.

Approximately 60 %

of the total water supply distributed by Finland’s waterworks consists of

groundwater. This figure also includes water from artificially maintained

reservoirs of groundwater fed from lakes and rivers.

Groundwater quality

The aquifers in

Finland’s glacial deposits rank in quality among the best reserves of

groundwater in the world. Groundwater in Finland is generally soft, with low

concentrations of dissolved substances and low pH (6-7).

Most of Finland’s

groundwater is of good quality, since it is better protected against

contamination than surface water. Harmful concentrations of arsenic, fluorine and

radon as well as iron and manganese occur in certain areas due to local

geological features. Groundwater reserves in Finland do not normally suffer

from contamination on a wider scale, since individual bodies of groundwater

tend to be small. Considerable contamination may be caused locally where salts

are used to de-ice slippery roads, on over-fertilised farmland, at garages and

service stations where oils may accidentally enter the soil, and following

accidents involving chemicals.

See also:

Water resources in Finland

During the period

1961-1990, the Finnish territory received a mean precipitation of 660 mm. Of

this amount, 341 mm evaporated, while 318 mm flowed into the seas or passed

over the national borders. The water storage was increased by 1 mm during this

period. The mentioned value 318 mm corresponds to a mean discharge of 3400 m3/s.

The study of some main hydro-meteorological variables

(precipitation, snow cover, river discharge) since early 1980s show decreasing

snow volumes in southern and central Finland. Consequently, some decrease in

spring high flows have been observed in these areas. Precipitation does not

reveal statistically significant trends or changes in general. The study of longer time series – starting

from 1910s or 1960s – highlights some increasing wintertime river

discharges.

The water plants deliver over 1.1 million m3 water

daily, and the households consume 3/5 of the water. About 60 % or 0.7 million m3/day

of the water is groundwater or artificial groundwater. Supply

networks of water plants cover about 90 % and sewage networks about 80 %

of Finnish households.

The Water

exploitation index (WEI) is one

of EEA’s core set indicators. The WEI is the ratio between the annual total

water abstraction and the available long-term freshwater expressed as a

percentage. The WEI for Finland is about 2 % that is one of the best WEI

values in Europe, and far below the value 20 % that is seen as the

critical value of WEI.

See also:

Water-borne

diseases in Finland

The notification

of food or water-borne epidemics came into effect in February 1997. The

municipal health authorities are responsible for the reporting. It is clear

that the identification of a water-borne epidemic is not always

straightforward.

A total of 56

epidemics were reported in 1998–2006 with about 16 800 persons fallen ill.

In more than 90 % of the cases, the municipal waterworks had delivered the

water. Private water supply was used in the rest of cases, for example in

different holiday or camping centres or rehabilitation centres. Of the waterworks,

most were small units with less than 500 customers. Almost always, the reason for

the epidemic is some harmful microbe infecting the drinking water. Even if the

groundwater in general is cleaner than the surface waters, the water-borne

epidemics are more often caused by the groundwater. WHO publishes regularly

fact sheets of outbreaks

of water-borne diseases. However, the level of monitoring and the quality

of reporting varies greatly between countries.

International evaluations of water policies

in Finland

Finland has been

placed near the top or at the top in several recent international comparisons

of the water and environmental sectors. Water policies in Finland are described

in more detail in the report to the UN: Country Profile: Freshwater and Sanitation, Finland, 2004.

United Nations World Water Assessment

Programme

United Nations/UNESCO

World Water Assessment Programme

(WWAP) monitors freshwater issues in order to provide recommendations, develop

case studies, enhance assessment capacity at a national level and inform the

decision-making process. In the first World Water

Development Report in 2003 water quality indicator values were assessed in

122 countries and Finland was ranked number one in this assessment. WWAP has

published three reports, the most recent one in

2009.

Water Poverty Index, 2003

In the

international Water Poverty Index published by the Centre for Ecology and

Hydrology in 2003, Finland was ranked the best in the world. A total of 147

countries were included in the comparison. The study assessed the extent of

water resources, the comprehensiveness of water supply, and water use, as well

as environmental impacts and general readiness for addressing water-related

concerns.

Document Actions

Share with others