All official European Union website addresses are in the europa.eu domain.

See all EU institutions and bodiesBathing is an extremely popular and important leisure activity in Europe. European citizens need to know if the quality of lakes, rivers, and coastal and transitional waters is poor, sufficient, good or excellent, so they can make informed decisions on where to bathe without health risks. The current assessment is published in the context of the Zero Pollution Action Plan and covers 21,658 officially designated bathing sites in the 27 EU Member States (EU-27), 119 in Albania and 196 in Switzerland.

Key messages

Bathing water quality in the EU remains high. In 2022, 85.7% of bathing water sites were rated excellent in the EU and minimum water quality standards were met at 95.9% of sites. This confirms the positive trend of previous years. Between 2010 and 2015, the share of EU bathing sites rated as excellent grew, to 87-89% for coastal bathing waters and 78-82% for inland bathing waters, and has remained stable ever since.

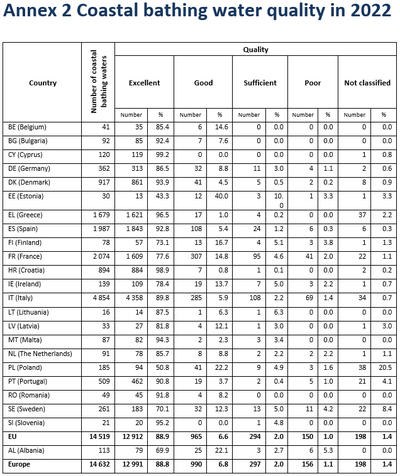

The quality of coastal bathing waters is generally better than that of rivers and lakes, because there is more frequent renewal and greater capacity for self-purification in the former. In 2022, 88.9% of coastal bathing water sites in the EU were classified as excellent, compared with only 79.3% of inland bathing water sites.

The health risk of swimming in EU lakes, rivers, and coastal and transitional bathing waters is very limited. In 2022, bathing water sites with poor water quality constituted 1.5% of all bathing waters in the EU, showing that adequate management measures were not always in place.

The number of bathing water sites designated in the EU increased by 0.5% (107 sites) between the 2021 and 2022 seasons, bringing the total to 21,658 in 2022. Compared with 2021, Poland (+36), France (+15) and Portugal (+14) reported the highest increases in the total number of designated bathing water sites in 2022. Increases were also observed in 14 other countries.

Bathing water quality is also reported on by non-EU countries. Albania reports on 119 bathing water sites, and a significant proportion (95%) of these are located along the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Switzerland, which has no coastline, reports on 196 bathing water sites, all of which are in rivers and lakes.

Quality of European bathing waters remains high

Bathing water quality in Europe has improved markedly in recent decades. Systematic monitoring and management introduced under the Bathing Water Directive (BWD) (EU, 2006), large investments in urban wastewater treatment plants and improvements in wastewater networks have led to a drastic reduction in organic pollutants and pathogens released in untreated or partially treated urban wastewaters. Thanks to these continuous efforts, bathing is possible in urban and formerly heavily polluted waters. This shows how solid and well-implemented policies can make a difference.

Figure 1. Proportion of bathing waters classified as excellent quality in 2022 (in the EU Member States, Albania and Switzerland)

Please select a resource that has a preview image available.

Monitoring and assessment of bathing water quality in Europe

EU Member States manage their bathing waters in accordance with the provisions set out in the Bathing Water Directive (BWD). Before the start of the bathing season, they identify national bathing water sites and define the length of the bathing season for each bathing water. Monitoring protocols are established for coastal and transitional waters, and rivers and lakes. Swimming pools and spa pools are exempt from the requirements of the BWD and are thus not part of the bathing waters inventory.

During the bathing season, local and national authorities take samples from bathing water sites and analyse them for the types of bacteria (E. coliand intestinal enterococci) that indicate pollution from sewage and livestock breeding. Polluted water can have impacts on human health, causing stomach upsets and diarrhoea if swallowed. Based on the levels of bacteria detected, bathing water quality is then classified as ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘sufficient’ or ‘poor’.

Member States establish their respective monitoring calendars, which must follow the provisions of Annex IV to the BWD:

- one pre-season sample is to be taken shortly before the start of the bathing season

- at least four samples (including the pre-season sample) are to be taken and analysed in the most recent season

- the time between sampling dates should not exceed 1 month.

For some countries, the quality classification of a large share of bathing water sites is not possible because the required number of samples for assessment is not collected. This is because the sites are newly identified or sampling was not possible due to Covid-19 restrictions or site reconstruction.

Out of 21,973 bathing water sites in Europe in 2022, 85.6% were of excellent quality (Figure 1). In four countries — Cyprus, Austria, Greece and Croatia — 95% or more of bathing water sites were of excellent quality. Moreover, in Malta, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia and Luxembourg all bathing water sites assessed met at least the minimum standard of sufficient quality in 2022. However, in four countries — Estonia, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland — less than 70% of bathing water sites were of excellent quality (Figure 2). One of the main requirements of the BWD is to ensure that all bathing water sites were of at least ‘sufficient’ quality by 2015. In the 2022 bathing season, this minimum water quality requirement was met by 95.9% of all EU bathing water sites.

Figure 2. Bathing water quality in Europe in the 2022 season (in the EU Member States, Albania and Switzerland)

Please select a resource that has a preview image available.

In the period 2009-2022, the share of EU bathing water sites with excellent water quality remained within the same range: 81-89% for coastal bathing waters and 60-82% for inland bathing waters (Figure 3). The bathing water quality of coastal waters is generally better than that of inland waters because of the more frequent renewal and higher self-purification capacity of open coastal waters. Moreover, many inland bathing waters of central Europe are located in relatively small lakes and ponds, and in rivers with a low flow. Especially in summer, these inland waters are more susceptible than coastal areas to short-term pollution caused by heavy summer rains or droughts.

Figure 3. Coastal and inland bathing water quality in the 27 EU Member States between 2009 and 2022

Please select a resource that has a preview image available.

Bathing water sites designated in the EU

The number of EU bathing water sites reported on increased between 1990 and 2010; 6,119 bathing waters were reported on in the summer of 1990 and 22,399 by the season 2009. The number then stabilised at around 22,000 bathing water sites every year.

In 2022, the most notable change compared with the previous season (2021) was that the total number of bathing water sites reported on increased, by 0.5% (or 107 sites) to 21,658 sites. Compared with the 2021 season, Poland (+36 sites), France (+15 sites) and Portugal (+14 sites), along with 14 other countries, reported on a larger number of bathing water sites.

Bathing water sites with no quality classification are a notable part of the overall bathing water inventory. These sites have not been classified because sample data sets are missing. This was the case particularly in the 2020 season because COVID-19 restrictions prohibited access to both bathing and sampling. In the 2020 season, 1,342 bathing water sites were not classified, followed by 711 in 2021 and 599 in the most recent season (2022).

Some bathing waters are still of poor quality

Swimming in bathing waters with poor water quality can result in illness. In 2022, 315 (1.5%) of all bathing water sites in the EU were of poor quality (Figure 3), compared with 1.9% in 2009. While the number of poor-quality sites has stabilised in recent years, problems persist at bathing waters of poor quality or bathing waters that are often affected by short-term pollution. It is imperative to assess the sources of pollution in the catchment areas of these sites and implement integrated water management measures that will restore water quality to at least the minimum required for bathing. At bathing water sites where the origins or causes of pollution are difficult to identify, special studies of pollution sources are needed.

Bathing water quality was poor at 3% or more of sites in only two EU countries: the Netherlands (with 25 bathing water sites, 21 of which are in lakes, or 3.4% of the total being of poor quality) and Sweden (with 19 bathing water sites or 4.1% being of poor quality). Meanwhile, in Albania, the number of poor-quality bathing water sites has dropped significantly since 2015, when 31 bathing water sites (39.1%) were rated as poor. In 2022, Albania had only eight poor-quality bathing water sites (6.7%), which could be attributed to the construction of several wastewater treatment plants in recent years. Bathing water sites classified as poor must be closed throughout the following bathing season and measures must be put in place to reduce pollution and eliminate hazards to the health of bathers.

Management measures are primarily expected to be implemented at bathing water sites where water quality is sufficient or poor. The Bathing Water Directive requires Member States to take several actions to ensure the safety of bathers:

- introduce adequate measures, including bathing prohibition or advice against bathing, with a view to preventing bathers’ exposure to pollution

- identify the causes and sources of pollution, and the reasons why sufficient quality status is not being achieved

- take appropriate measures to prevent, reduce or eliminate the causes of pollution, such as the implementation of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (EU, 1991), focusing on reducing sewer overflows

- alert the public through a clear and simple warning sign, and inform them of the causes of the pollution and measures being taken.

The number of bathing water sites with poor water quality has stabilised in recent years. This is because the quality of some waters has improved, while the quality of some bathing waters classified as being of sufficient quality has deteriorated to poor quality, and others have been excluded from the monitoring programme. In 2021, 332 bathing water sites in the EU were of poor quality. Of these, 223 remained of poor quality in 2022. Of the other 109 sites, the water quality of 86 improved to at least sufficient between 2021 and 2022. The remaining 23 sites were either excluded from the monitoring programme or could not be assessed. The latter was because of measures that affected the quality of bathing water, or because the minimum number of required monitoring samples for assessment was not available.

Bathing waters that have been classified as poor for at least five consecutive years, are required by the Bathing Water Directive to introduce a permanent bathing prohibition or a permanent advice against bathing. In the period 2017-2021, 45 bathing waters were classified as poor in the EU: 31 in Italy, eight in France, two in the Netherlands, and one in Czechia, Estonia, Poland and Sweden respectively.

Out of these 45 bathing waters, nine managed to improve their quality to at least the sufficient level in 2022. Five were excluded from the monitoring programme, and measures to improve water quality are being implemented at one bathing site. However, 30 bathing waters continued to be classified as poor also throughout the 2022 season. It was reported that bathing prohibition or advice against bathing was in place only at two-thirds of these bathing waters.

Review of the Bathing Water Directive

In the context of the European Green Deal, notably the zero pollution action plan, the European Commission is currently assessing whether the Bathing Water Directive (BWD) is still fit for its purpose of protecting public health and improving water quality, or if there is a need to improve the existing rules and propose relevant updates, including new parameters. During the review process, stakeholders interested or directly involved in the implementation of the BWD were consulted through a number of activities, including an open public consultation, two thematic workshops organised in November 2021 and April 2022, or the most recent stakeholder validation conference on the evaluation of the directive. The feedback received via these activities will be reflected in the Commission evaluation report, which is expected to be published in the first half of 2024.

The BWD has not been analysed in isolation, as its implementation is supported by a broad framework of EU water legislation, including the Water Framework Directive (WFD), the Environmental Quality Standards Directive (EQSD), the Groundwater Directive (GWD), the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) and the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive (UWWTD).

As part of the proposal for a revised UWWTD stronger action storm water overflows that have an impact on bathing water quality will need to be taken. It is proposed that Member States and their , develop integrated urban wastewater treatment plans (Article 5). These plans will have to contain measures for the reduction of pollution coming from storm water overflows and urban run-off, and shall prefer green solutions and only consider grey infrastructure as a last resort. This requirement will be very beneficial to coastal waters and bathing water sites.

The proposed directive amending the WFD, the GWD and the EQSD aims to update the relevant lists of chemical pollutants and their standards, with a focus on pollutants of emerging concern, in light of new scientific developments. The proposal also calls for more frequent updates of the chemical and ecological status of surface water and simplified reporting using automated data delivery mechanisms. The EEA’s web map on the state of bathing water has been a source of inspiration for this, as it is much more frequently updated than EU-level information for the WFD (the latter only every 6 years). The MSFD is undergoing an evaluation process to assess whether or not its objectives to maintain healthy, productive and resilient marine ecosystems, while securing a more sustainable use of marine resources, have been met. The Commission evaluation report is expected by the end of 2024.

Clean bathing waters in urban areas support European Green Deal objectives

Achieving clean and safe bathing waters is intricately linked to the goals of the Zero Pollution Action Plan and more widely to the objectives of the European Green Deal aiming to shift European economies towards net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and ensuring sustainable resource use. This includes the restoration and protection of European marine and fresh water ecosystems and their services, the promotion of environmentally friendly food production systems and the implementation of sustainable blue economies through green infrastructure in coastal areas.

Around half of European citizens living in towns and cities have access to urban bathing waters, and urban bathing is increasingly possible and popular. These waters are designated and monitored under the provisions of the Bathing Water Directive, which safeguards public health and protects the aquatic environment. The European Topic Centre on Inland, Coastal and Marine Waters published a report on the benefits of bathing waters in European cities (ETC/ICM, 2022). The report highlights the socio-economic benefits of clean and safe urban bathing waters, including the direct benefits to bathers and indirect benefits to the health of the wider ecosystem.

Of all European bathing water sites, more than 1,800 (8%) are located in almost 200 cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants each and are therefore a valuable attribute of urban public spaces. The main socio-economic and environmental benefits that stem from clean and safe urban bathing waters in Europe include better public health, increased ecosystem services, higher recreational value with an overall improvement of public space and better quality of life.

European cities with bathing waters

About 70% of bathing water sites in large European cities (cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants) are coastal (1,274), located in almost 90 urban areas. The vast majority of European bathing water sites are found in 47 Mediterranean cities across four countries: France (280 bathing water sites in nine cities), Greece (37 bathing water sites in seven cities), Italy (343 bathing water sites in 13 cities) and Spain (192 bathing water sites in 18 cities). Other bathing water sites are distributed throughout seven cities in Portugal, and two cities in each of Albania, Croatia and Denmark. Some coastal European cities also have river and lake bathing water sites. For instance, Helsinki has all three categories of bathing water site, while Stockholm has 27 lake bathing water sites and two coastal bathing water sites, reflecting the importance of the bathing water culture to the urban communities in these cities.

One quarter of European urban bathing water sites are in lakes, spread across more than 100 cities, while only 39 designated urban bathing water sites are in rivers. European capitals including Budapest, Helsinki, Paris, Riga, Vienna and Vilnius all have river bathing water sites. Budapest has two, Helsinki has four, Riga, Paris and Vilnius each have three, and Vienna has 19. Some cities have both lake and river bathing water sites.

Managing the quality of urban bathing water sites in lakes is often less complex than in rivers because of the closed geography of lake waterbodies, compared with the wide catchments of many rivers and the discharge of wastewater from many wastewater treatment plants along river stretches. Designated river bathing water sites can be considered a sign of successful water management throughout entire river basins and, if located in city centres or downstream of cities, can be a sign of efficient sewage treatment management. For instance, in Copenhagen and Essen, city authorities have developed advanced warning systems to control pollution risks to human health, allowing rapid management of their urban bathing water sites. In 2020, Paris initiated a plan that was supported by a EUR1.4 billion investment to make the Seine swimmable for the 2024 Olympics, as it will be used for the swimming leg of the triathlon competition. Afterwards, in 2025, locals will have access to around 20 swimming areas along the Seine and an upstream tributary, the Marne.

Good water quality in urban aquatic systems — and especially in bathing waters — is a sign of the successful management of the problems of 20th century industrial development in Europe. Key ongoing problems include pollution loads reaching cities along rivers from upstream areas, storm water overflows from city sewers during heavy rains, sudden surface run-off from paved urban areas, built-up water banks, nutrient pollution (mostly from inputs of nitrogen and phosphorus), artificially narrowed riverbeds, plastic litter in bathing waters and insufficient riparian vegetation. Many cities have shown that success is possible when residents, environmental managers, urban planners and politicians come together for a common purpose.

Find your local beach!

Member States are required by the Bathing Water Directive to use ‘appropriate media technologies, including the Internet’ to actively disseminate information (EU, 2006). Today, countries maintain national or regional websites with detailed information on each bathing water site. These websites generally include a map-search function and allow a user to see monitoring results, both in real time and for previous seasons.

At the European level, bathing water information is made available to the public through the EEA’s bathing water web pages which includes country profiles. Users can check bathing water quality on an interactive map, explore details through a link to the national online bathing water profile and make comparisons with previous years.

Briefing no. 13/2023

Title: European bathing water quality in 2022

EN HTML: TH-AM-23-017-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-581-2 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/04489

EN PDF: TH-AM-23-017-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-580-5 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/74416

- Starting with agglomerations above 100,000 population equivalent (p.e.) followed by those of 10,000-100,000 p.e.↵

EU, 1991, Council Directive of 21 May 1991 concerning urban waste water treatment (91/271/EEC) (OJ L 135, 30.5.1991, p. 40-52).

EU, 2006, Directive 2006/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 February 2006 concerning the management of bathing water quality and repealing Directive 76\160\EEC (OJ L 64, 4.3.2006, p. 37-51).

ETC/ICM, 2022, Benefits of bathing waters in European cities, ETC/ICM Report 4/2022, European Topic Centre on Inland, Coastal and Marine Waters (https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-icm/products/etc-icm-reports/etc-icm-report-4-2022) accessed 23 May 2023.