Towards an EU policy framework for just sustainability transitions

The European Green Deal aims to transform the EU into a climate-neutral, fair and prosperous society with a circular economy by 2050. The 8th Environment Action Programme reiterates the EU’s long-term 2050 vision of living well, within planetary boundaries. These ambitions are to be achieved through ‘sustainability transitions’ that require radical changes to our core systems of production and consumption — energy, mobility, food and the built environment — as well as to our established ways of living and working.

The commitment of the European Green Deal to ‘leave no one behind’ and the commitment of the European Pillar of Social Rights to build a fairer more inclusive society, provide overarching guiding principles for just sustainability transitions that together with concrete measures and initiatives, are a clear recognition of how the social and environmental problems facing Europe are interwoven.

These instruments intend to safeguard social welfare and ensure a fair and just transition to climate-neutral societies, acknowledging that inequalities exist between regions in Europe and that certain social groups will be disproportionately affected. They include the Just Transition Mechanism (including the Just Transition Fund), which was launched in 2020, the subsequent 2022 Council recommendation on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality and the Social Climate Fund.

Recent research from the United Nations and the EEA highlights the impact of climate change on vulnerable communities and disadvantaged groups, who often have a lower share of the responsibility for creating environmental problems (EEA, 2022, IPCC, 2022). These groups will also bear significant future costs from adaptation to the impacts of climate change, pollution and environmental degradation.

While the EU sets the direction for just and equitable transitions, an understanding is still lacking in terms of how justice considerations and environmental sustainability goals can be jointly delivered through effective policy interventions (Avelino et al., 2023).

For instance, the recently agreed EU Nature Restoration Law broadens the debate around justice to include nature and the environment and extends the focus from protecting ecosystems to restoring degraded or destroyed ecosystems. There is a need to document experiences and develop recommendations on how to design, implement and evaluate policies to achieve just sustainability transitions for humans and other species in nature. This briefing is a first step towards addressing this need by describing some of the key elements and relationships.

What are just sustainability transitions and why are they important?

Sustainability transitions are processes of long-term structural change towards more sustainable societal systems. They include profound changes in ways of doing, thinking and organising, as well as in underlying institutions and values (Loorbach et al., 2017). This entails decisions about the direction of change, in a context where there are many legitimate perspectives on desirable futures and how to reach them.

The effective governance of transitions requires participatory processes that enable a diverse set of stakeholders to identify shared visions and goals, and credible pathways to reach them. Prerequisites include democratising access to environmental information, increasing public participation in decision-making and providing access to justice in environmental matters as laid out in the Aarhus Convention.

Large-scale, systemic change involves trade-offs. It creates winners and losers and may trigger unintended outcomes that disproportionately affect vulnerable territories and social groups. This can exacerbate existing inequalities and generate resistance to change (Agyeman, 2013; Swilling, 2020).

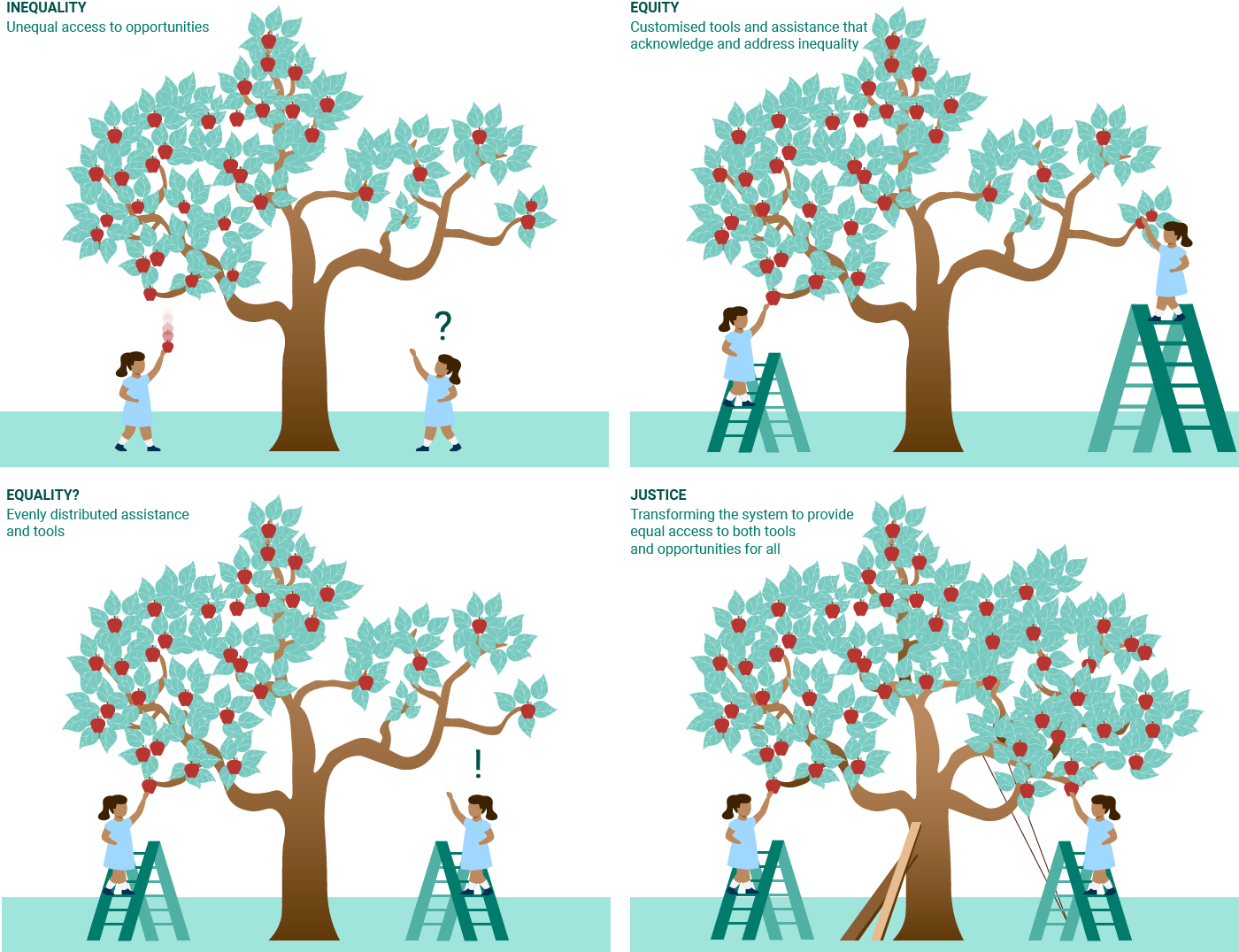

The concepts of inequality, justice and equity are themselves complex as Figure 1 below illustrates. Achieving sustainability will have significant distributional consequences, making it critical to pay careful attention to equity considerations (IPCC, 2022). Policies should monitor and anticipate potential losses and the unequal distribution of costs and benefits arising from systemic changes with the aim of sharing these costs across society (EEA, 2022).

Sustainability transitions can be considered as ‘just’ when these processes of transformative change ‘improve the quality of life of current and future generations, both human and non-human, within ecological boundaries while eliminating injustices that are triggered or exacerbated by unsustainability and its underlying causes’ (Avelino et al., 2023).

Source: EEA, 2024. Adapted from Tony Ruth from Maeda (2019) with permission under CC license.

Key dimensions of justice

When considering how to capture the concepts of justice in sustainability transition policies, it is useful to distinguish between the key dimensions of justice as described below.

Distributional justice relates to how the costs and benefits of human activity, as well as policies to manage these activities, are allocated across our society and to other species in the natural environment, as well as to the values and principles according to which goods and services are allocated. It concerns not only which entities pay costs and which receive benefits, but also their perceptions of what constitutes a cost or a benefit (Langemeyer and Connolly, 2020; Biermann and Kalfagianni, 2020; Wijsman and Berbés-Blázquez, 2022). Sustainability transitions must also tackle existing injustices linked to environmental degradation and climate change.

Air pollution poses the greatest environmental health risk in Europe but the impacts of air pollution are unequally distributed across our society. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) causes more premature deaths in Europe than any other ambient air pollutant. Monitoring PM2.5 levels is therefore considered useful for exploring income-related inequalities in the distribution of the health impacts of air pollution. An EEA indicator explores these inequalities by comparing the exposure to PM2.5 experienced by people living in the EU’s poorest regions with those living in its wealthiest regions. In an environmentally equal Europe, poverty and pollution would not be correlated. However, monitoring data shows that despite improvements in air quality in both the richest and poorest regions of the EU 2007 and 2020, inequalities remain, with levels of PM2.5 concentrations consistently higher by around one third in the poorest regions. This shows a lack of progress in reducing disparities in exposure to air pollution across Europe (EEA, 2023).

Procedural justice focuses on fairness in the institutions, procedures and practices of decision-making, and the judicial processes and the extent to which these are inclusive. It looks at who participates in and benefits from decision-making processes and why, and how to define and deliver inclusive participation. This entails the identification and inclusion of those entities typically not represented in decision-making and judicial processes, such as homeless people, undocumented people, socially excluded groups, children, future generations and other species in nature, such as animals and plants (Langemeyer and Connolly, 2020; Wijsman and Berbés-Blázquez, 2022).

Box 2: Delivering procedural justice in the EU.

The EU and its 27 Member States are all parties to the Aarhus Convention – the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Convention on access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters.

The convention aims to ensure environmental democracy by laying down a set of basic procedural rights for the public, imposing obligations on public authorities to make these rights effective, increasing transparency and making governments more accountable to people. The Aarhus Convention is translated into EU law through several legislative acts.

The Access to Environmental Information Directive aims to ensure that environmental information is systematically made available by the authorities to the public either actively or upon request. The Public Participation Directive 2003/35/EC provides for public participation when formulating certain plans and programmes relating to the environment. Provisions for public participation in environmental decision-making are also found in a number of environmental directives, such as the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive 85/337/EEC and the Strategic Environmental Assessment Directive 2001/42/EC.

Recognitional justice implies the recognition of underlying systemic injustices and representation of dignity, values and identities of humans and other species. When referencing humans, this dimension refers both to individuals and social groups and entails recognising and respecting how different values, preferences and needs are rooted in diverse histories, identities and cultural backgrounds. For other species, this implies recognising the intrinsic and inherent value of nature regardless of its utility to humans (Wijsman and Berbés-Blázquez, 2022).

Box 3. Recognitional Justice: the case of the Roma people.

A recent report published in 2020 documents cases of social exclusion of Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe, whereby Roma people were living in marginal and polluted areas, without access to basic services such as water and sanitation. These poor environmental conditions seriously impact their health and welfare (EEB, 2020). The non-governmental organisations, the European Environmental Bureau and the European Roma Grassroots Organisations Network, have highlighted the environmental injustice and social inequality the Roma communities face and are campaigning for recognitional justice for these marginalized communities (EEB, 2024).

Box 4. Engagement of vulnerable groups in adaptation planning and implementation

The need for adaptation to climate change is increasingly urgent. Adaptation strategies and plans are being progressively developed and implemented across Europe. Ensuring that no one is left behind requires a focus on equity and the meaningful engagement of vulnerable groups at all stages of adaptation planning, implementation and monitoring.

EU policies and instruments such as the European Climate Pact and the European Mission on Adaptation emphasis on higher levels of citizen engagement. A recent EEA briefing, Towards ‘just resilience’: leaving no one behind when adapting to climate change, looks at how climate change affects vulnerable groups and how these impacts can be prevented or reduced through equitable adaptation actions. It also presents examples of how vulnerable groups are already involved in developing equity-oriented policies and measures in some European countries.

For example, in Finland, children, youth, the elderly and the Sami indigenous people were consulted on climate change planning. In Slovenia, municipalities engage with those particularly vulnerable to climate change impacts as they are required to consult with representative organisations on a wide range of activities from civil protection in natural disasters to elderly care (EEA, 2023).

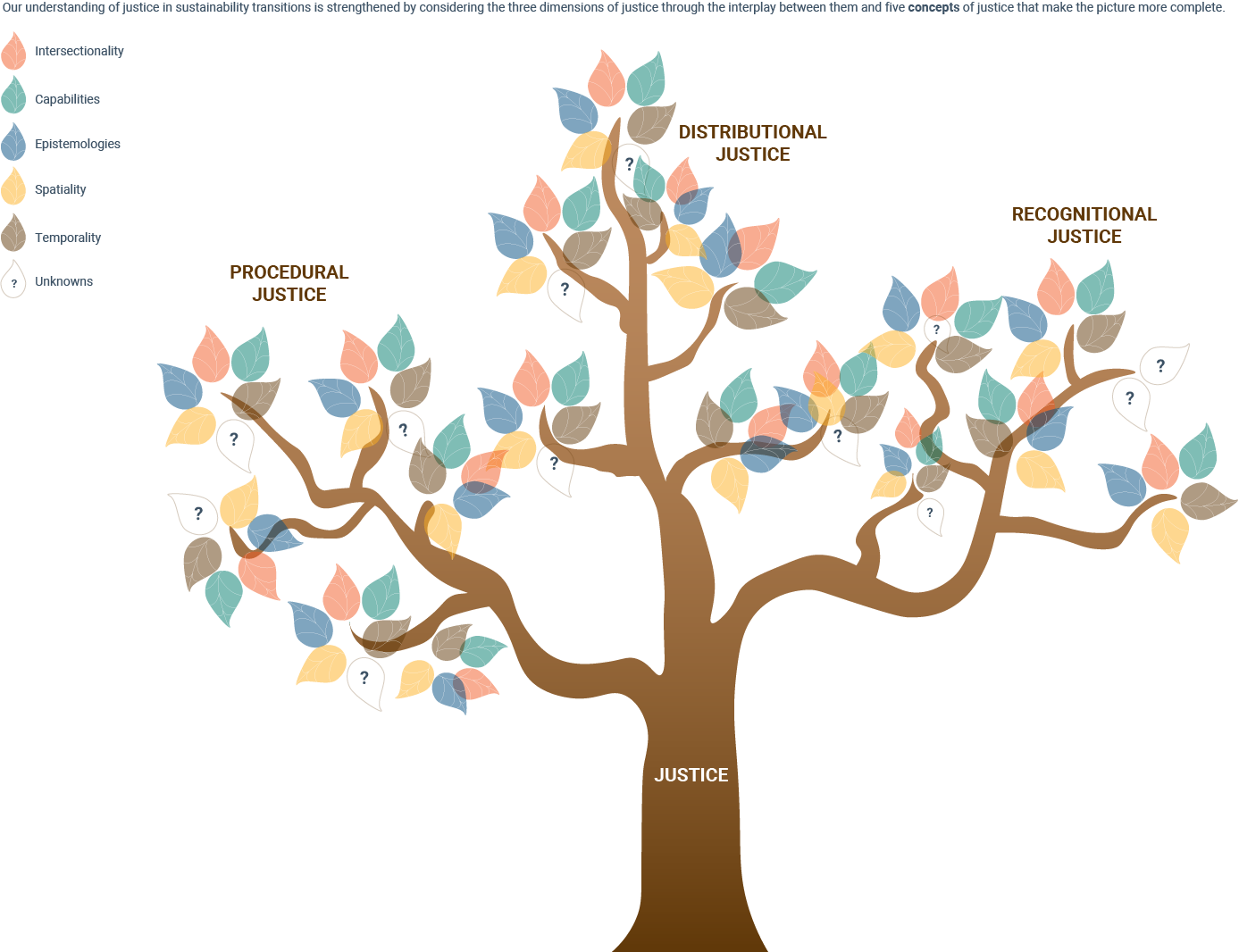

Our understanding of justice in sustainability transitions is strengthened by considering the three dimensions of justice through the interplay between them and five concepts of justice that together make the picture more complete.

The extent to which individuals connect to different dimensions of justice depends upon their circumstances. For example, an individual’s age, sexuality, gender, ethnicity, nationality, socio-economic and legal status may influence their perception of justice as well as their access to it. Without acknowledging such intersectionality, policymakers may fail to understand the diversity of society and therefore be at risk of addressing the needs of certain groups while neglecting others (Crenshaw, 1989; Gonzalez, 2020).

In addition, an individual or group’s capabilities to mobilise resources, participate in decision-making processes and take advantage of the opportunities that policies may offer will vary (Bierman and Kalfagianni, 2020; Nussbaum, 2011).

In evidence-based policymaking, an important aspect is how knowledge, including indigenous knowledge, is recognised and treated as relevant, valid, and legitimate in problem-framing and decision-making. Epistemic injustice entails the exclusion of individuals or groups from the process of creating and assessing knowledge (Fricker, 2007; Wijsman and Feagan, 2019; Ghosh et al, 2021).

The spatial and temporal reach of policies affect their effectiveness in delivering justice. Spatiality concerns the geographic area addressed by legislation and the level at which it is implemented, be it local, regional, national or international (Langemeyer and Connolly, 2020; Soja, 2010; Stevis and Felli, 2020).

Temporality concerns how policies address issues of justice over time, for example, the needs of future generations for a safe and healthy environment, and the responsibility of current generations to restore past environmental degradation (Langemeyer and Connolly, 2020; Gonzalez, 2020).

The resulting conceptual framework for just sustainability transitions is categorised according to different dimensions of justice and concepts for justice as presented in Figure 2.

Box 5. Distributional and recognitional justice in the case of the Taranto plan

Taranto, a city in southern Italy, has been faced with social, economic and environmental challenges due to a dependency on the iron and steel industry. A grassroots initiative called Plan Taranto, aiming to transition the local economy from steel manufacturing to tourism and agroecology, includes efforts to restore brownfield sites and contaminated industrial land, and to find new sustainable ways to reuse industrial buildings in line with circular economy principles.

The local community has been involved in developing and steering the plan, which prioritises both distributional and recognitional justice. The plan aims to ensure that people impacted negatively by the changes are given a voice, directly addressing concerns about job losses. The creation of new jobs, notably in agroecology, not only supports the community but also contributes to easing environmental pressures.

Source: EEA, 2024.

Thematic and domain-specific justice

There are different types of justice each with a focus on particular themes or domains. Examples include epistemic justice, climate justice, energy justice, food justice, urban justice and restorative justice. The three dimensions of justice mentioned earlier (distribution, procedure, and recognition) and the five concepts of justice (intersectionality, capabilities, epistemologies, spatiality and temporality) are critical across all those different thematic and domain-specific types of justice.

Restorative justice

Restorative justice recognises how past inequities continue to shape present conditions and aims to address these injustices, deliver resolution, and enable healing (Forsyth et al., 2022; McCauley and Heffron, 2018). It is particularly relevant when remediating degraded environments and addressing the impacts of climate change.

The Nature Restoration Law, for example, provisionally agreed in November 2023, extends the focus from protecting ecosystems to restoring degraded or destroyed ecosystems. (see box on the Nature Restoration Law).

In the context of sustainability transitions, restorative justice centres on processes to compensate for past harm to humans and other species and ecosystems. Such processes involve multiple stakeholders with diverse perspectives and focus on identifiable harm and victims, and the individuals, groups and institutions that take responsibility and can be held accountable for harm. Restorative justice is also important in the design of new policies, which must avoid causing intergenerational impacts. Outcomes can take the form of financial compensation for losses, or the restoration of natural areas degraded through human activity. This may include operations to restore land and aquatic ecosystems, while ensuring that remediation efforts do not impact negatively on vulnerable communities (Forsyth et al., 2022).

An example of steps towards restorative justice in a European country is the response to the detection of large-scale soil and groundwater pollution around a per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) production plant in Antwerp, Belgium operated by 3M (Vito, 2022). Following several months of negotiation, 3M agreed to pay EUR 571 million in response to the pollution near its factory including: EUR 250 million for priority remedial actions, EUR 100 million to the Flemish Government for PFAS related actions and EUR 100 million to support the Oosterweel project to complete the Antwerp ring road where the pollution was first revealed. More recently and in response to follow-up efforts to test the blood of nearby residents for contamination with PFAS, 3M has been ordered by a court in Antwerp to pay provisional damages of EUR 2,000 in compensation to a local family whose blood was contaminated by its activities.

Box 6. EU Nature Restoration Law: bringing nature back.

The European Green Deal launched in December 2019 sets out an ambitious roadmap to transform the European Union into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy. The Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, published in May 2020, couples these aims with a zero-pollution ambition and cross-cutting environmental objectives to achieve climate-neutrality, recover biodiversity, and restore degraded ecosystems. The EU Nature Restoration Law, provisionally agreed on in November 2023, and the European Climate Law adopted the year prior, will be important steps towards delivering the key commitments of the European Green Deal and are central to achieving overarching EU climate and biodiversity objectives.

The Nature Restoration Law is the first piece of legislation explicitly focused on the restoration of nature in EU Member States. It will support the recovery of degraded ecosystems by improving their structure and functions to enhance biodiversity and its resilience. It sets a binding target at EU level and requires Member States to implement effective restoration measures on at least 20% of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030. By 2050, measures should be in place for all ecosystems in need of restoration. This target builds on the international commitment undertaken by the EU and its countries as a party to the global Convention on Biological Diversity.

The main instruments of the Nature Restoration Law are the national restoration plans, where Member States will identify restoration measures required to meet the binding targets set in the law and specify the total area to be restored, as well as a timeline covering the period up to 2050. The preparation, review, and implementation of national restoration plans incorporate procedural justice ensuring access to environmental information and involving key stakeholders in public decision-making processes. In line with the Aarhus Convention, the plans should document information on public participation and how the needs of local communities and the general public have been considered. It also contains elements of recognitional justice and aims to restore nature in all ecosystems, including forests, agricultural land, marine, freshwater, and urban ecosystems. Restoration is framed as living and producing together with nature by improving biodiversity across all land and sea, including areas where economic activity takes place, such as managed forests, agricultural land, and cities. In terms of distributional justice, Member States should explore opportunities to promote the deployment of private and public support schemes that benefit stakeholders implementing restoration measures.

Defining justice in the context of sustainability transitions

The definitions above explain the different dimensions of justice and how an individual’s or group’s circumstances can affect their access to justice. What does this mean for efforts to deliver justice in the context of sustainability transitions?

1. For whom?

Efforts to deliver justice tend to focus on certain social groups while neglecting other social groups and, indeed, other species in nature. For example, without adequate compensatory measures and educational support for reskilling, members of communities dependent on coal mining for their livelihoods may not consider efforts to transition to green energy to be just. It is necessary to consider the needs of a broad range of social groups in the context of achieving just sustainability transitions.

2. Positionality

Who we are and where we come from shapes our understanding of and approaches to addressing social and environmental injustices. For example, a policymaker who has lived in a marginalised neighbourhood might appreciate the challenges of green gentrification faster and easier than someone who has not. This requires policymakers to be aware of their positionality, to acknowledge different perspectives and to engage with other stakeholders.

3. Multi-dimensionality

Justice is a complex and multi-dimensional concept and therefore processes to deliver justice within the context of sustainability transitions will inevitably be subject to blind spots and unpredictability. For instance, when considering justice in our food systems globally, we may overlook injustices at the local level and vice versa. We may also prioritise justice for humans at the cost of other species. Policymakers face the challenge of capturing multiple dimensions, while acknowledging likely blind spots.

4. Tensions

Sustainability transitions are characterised by tensions and conflicting trade-offs. For instance, there is a trade-off between the urgent need to address the unequal distribution of the impacts of climate change on the one hand and the time required for inclusive decision-making on the other hand. When prioritising certain dimensions of justice over others, it is important to be transparent about the rationale and how this affects processes and outcomes.

5. Unintended consequences

Every intervention and every decision not to intervene runs the risk of having unintended consequences that generate injustices. For instance, greening urban areas and implementing nature-based solutions may lead to green gentrification, rising property prices and the displacement of marginalised communities. Policymakers should therefore seek to anticipate negative consequences and, where possible, prevent them or compensate the affected groups.

6. Continuous commitment

Delivering justice requires a continuous commitment and a process to assess progress. While policymakers cannot always anticipate the negative impacts of policies, building in processes to evaluate polices can enable them to identify injustices in terms of distribution, procedure and recognition, and adjust policies to redress such impacts. For example, taxes on energy consumption are often regressive, disproportionately burden lower-income households and can in some cases exacerbate existing inequalities or create new ones.

EEA–Next steps in developing just sustainability transitions

This briefing presents a framework for understanding justice in the context of sustainability transitions. Policy interventions aiming to foster transitions towards sustainable futures operate across complex societal systems at different scales. As such outcomes can be unpredictable. Such broad sustainability transition policies have the intention of creating better outcomes but are unlikely to completely avoid unjust impacts.

In the next phase of our work on justice in sustainability transitions, the EEA will use this conceptual framework to develop recommendations to support the design, implementation, and evaluation of just sustainability transition policies that ‘leave no one behind’.

References

Agyeman, J., 2013, Introducing just sustainabilities: policy, planning and practice, Zed Books.

Avelino, F., et al., 2023, Towards a robust conceptualization of justice for sustainability transitions: A literature review for the European Environment Agency. Unpublished.

Biermann, F. and Kalfagianni, A., 2020, ‘Planetary justice: A research framework’, Earth System Governance, 6, p. 100049 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2589811620300082). Last accessed 05.01.24.

Crenshaw, K., 1989, ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’, University of Chicago Legal Forum (http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8).

European Environmental Bureau (EEB), 2020, Pushed to the Wastelands: Environmental racism against Roma communities in Central and Eastern Europe. Last accessed 07.02.24.

European Environmental Bureau (EEB), 2024, Bearing the brunt: Roma and traveller experiences of environmental racism in Western Europe. Last accessed 07.02.24.

EEA, 2022 (Updated, 2023), Towards ‘just resilience’: leaving no one behind when adapting to climate change, Briefing, European Environment Agency. Last accessed 23.01.24.

EEA, 2023, European Union 8th Environment Action Programme — European Environment Agency (europa.eu) Last accessed 07.02.24.

Forsyth, M., et al., 2022, ‘Environmental Restorative Justice: An Introduction and an Invitation’, in: The Palgrave Handbook of Environmental Restorative Justice, pp. 1–23, Springer International Publishing.

Fricker, M., 2007, Epistemic injustice: power and the ethics of knowing, Oxford University Press.

Ghosh, B., et al., 2021, ‘Decolonising transitions in the Global South: Towards more epistemic diversity in transitions research’, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 41, pp. 106–109 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.029). Last accessed 23.01.24.

Gonzalez, C. 2020, ‘Racial capitalism, climate justice, and climate displacement’, Oñati Socio-Legal Series, symposium on Climate Justice in the Anthropocene, 11(1), pp. 108–147 (https://doi.org/10.35295/osls.iisl/0000-0000-0000-1137).

IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf). Last accessed 12.02.2024.

Langemeyer, J. and Connolly, J. J. T., 2020, ‘Weaving notions of justice into urban ecosystem services research and practice’, Environmental Science & Policy, 109, pp. 1–14 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.03.021). Last accessed 23.01.24.

Loorbach, D., et al., 2017, ‘Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change’, Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42, pp. 599–626 (https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340). Last accessed 23.01.24.

McCauley, D. and Heffron, R., 2018, ‘Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice’, Energy Policy, 119, pp. 1–7 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014). Last accessed 23.01.24.

Nussbaum, M. C., 2011, Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach, Harvard University Press.

Soja, E. W., 2010, Seeking spatial justice, University of Minnesota Press.

Stevis, D. and Felli, R., 2020, ‘Planetary just transition? How inclusive and how just?’, Earth System Governance, 6, p. 100065 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100065). Last accessed 23.01.24.

Swilling, M., 2020, The Age of Sustainability: Just Transitions in a Complex World, Routledge.

Vito, 2022, Studie naar PFAS in lucht en deposities in de omgeving van 3M en Zwijndrecht, 2022/HEALTH/R/2680, VITO NV (https://www.vmm.be/publicaties/studie-naar-pfas-in-lucht-en-deposities-in-de-omgeving-van-3m-en-zwijndrecht#:~:text=3M%20en%20Zwijndrecht-,Studie%20naar%20PFAS%20in%20lucht%20en%20deposities%20in%20de%20omgeving,3M%2Dsite%20en%20de%20Oosterweelwerf) Last accessed 12 February 2024.

Wijsman, K. and Feagan, M., 2019, Rethinking knowledge systems for urban resilience: Feminist and decolonial contributions to just transformations, Environmental Science & Policy, 98, pp. 70–76 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.04.017). Last accessed 23.01.24.

Wijsman, K. and Berbés-Blázquez, M., 2022, ‘What do we mean by justice in sustainability pathways? Commitments, dilemmas, and translations from theory to practice in nature-based solutions’, Environmental Science & Policy, 136, pp. 377–386 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.06.018). Last accessed 23.01.24.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 26/2023

Title: Delivering justice in sustainability transitions

EN HTML: TH-AM-24-003-EN-Q - ISBN: 978-92-9480-629-1 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/695598

EN PDF: TH-AM-24-003-EN-N - ISBN: 978-92-9480-628-4 - ISSN: 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/228718

Document Actions

Share with others