Indicator 19 (and 17): Internalisation of external

costs

- Although there are many methodological problems,

it is estimated that in 1991 only about 30 % of road infrastructure

and external costs were recovered from users and only about 39 %

for rail.

- Internalisation of transport costs is expected

to lead to efficiency improvements, while non-transport taxes should

decrease as a result of external costs being transferred from government

to transport users. The impact on GDP growth or industrial competitiveness

should, again in principle, therefore be small.

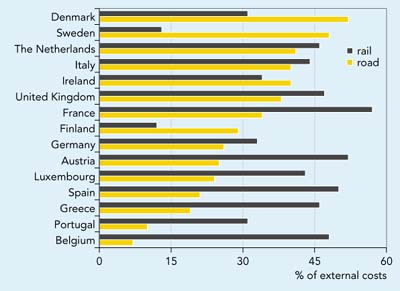

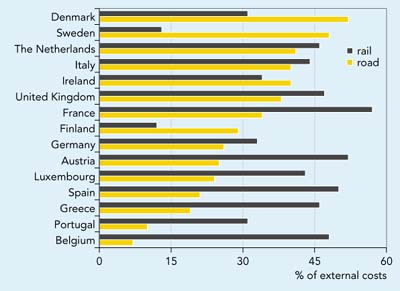

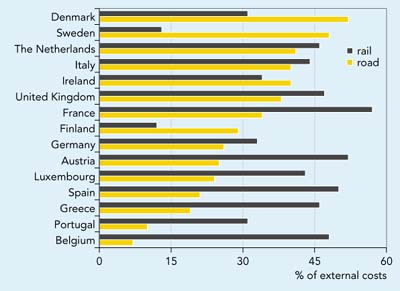

Figure 5.8: Proportion of external and infrastructure

costs covered by revenues in transport (1991)

Source: EEA, 1999b, using data from

UIC, 1994 and ECMT, 1998

Objective

Recover the full costs of transport

including externalities from users.

Definition

The proportion of external costs that

are covered by revenues from relevant taxes and charges.

Note: External costs are those that transport

users inflict on others, such as noise, air pollution, accidents, climate

change, congestion, and infrastructure costs. With improvements in data

and method they could also include the use of land, solid waste generation,

water pollution, fragmentation of human and animal communities, and the

aesthetic impacts of infrastructure and traffic.

|

Policy and targets

An important aspect of the EU transport

policy is the concept of fair and efficient pricing, described in the Commission

Green Paper on Fair and Efficient pricing (CEC, 1995). This proposes to apply

the polluter-pays principle to ensure that transport users pay all the costs

they impose on others. External costs should be recovered via taxation, and

these taxes should be differentiated according to the environmental performance

of each mode.

Internalisation is a policy instrument

to correct market imperfections and the resulting inefficient allocation of

resources that can occur when costs are not borne by those who incur them. Internalisation

of external costs such as those related to air pollution, noise and accidents

should also reduce the environmental costs of transport by providing incentives

to reduce demand.

It is widely accepted that transport prices

do not recover external costs, but there is less agreement about the extent

of the shortfall. Any move towards internalising costs should however produce

significant social and community benefits. The recent ECMT report on policies

for internalisation concludes that the main response to internalisation is likely

to be significant technological and operational efficiency improvements. The

overall effect on demand for mobility and modal shares is likely to be relatively

small. But the increase in transport costs will be offset by efficiency improvements

and there will be opportunities for reducing non-transport-related taxes. So

the impact on GDP growth or industrial competitiveness is likely to be small

(ECMT, 1998).

Findings

The external costs of transport in the

EU caused by environmental damage (noise, local air pollution, and climate change)

and accidents are estimated to be around 4 % of GDP (ECMT, 1998).

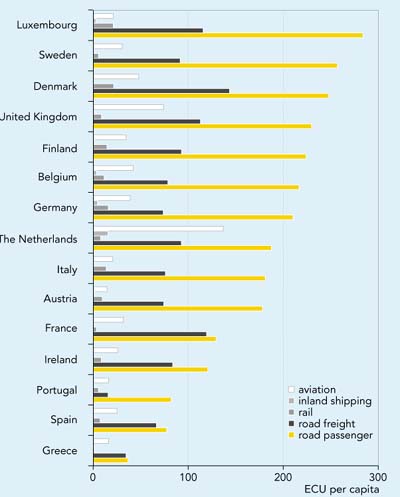

In 1991, cost recovery (Figure 5.8) was

generally higher for rail (39 %) than for road transport (30 %) (with

the exception of the Nordic countries and Ireland). This is partly due to rail

infrastructure subsidies being used to encourage greater use of rail transport.

Overall, the degree of internalisation remains below 50 %. The highest

cost recovery rates are found in France, Austria, Denmark and Spain, while Belgium

and Portugal show the lowest.

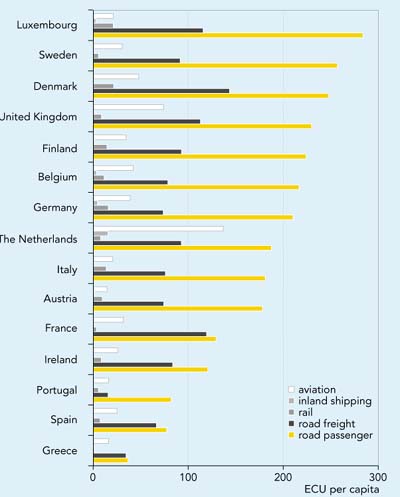

It is estimated (see Figure 5.9) that of

total EU external transport costs:

- road traffic accounts for about 83 %;

- aviation for about 13 %;

- rail for about 3 % (Germany, Italy, the United

Kingdom and Spain dominate with three-quarters of this);

- inland shipping for about 1 % (only significant

in Germany and the Netherlands).

Figure 5.9: External costs of transport per capita

(1991)

Source: UIC, 1994

Currently, it is impossible to calculate internalisation

percentages for inland shipping and aviation, as data on taxes and charges is

not available. Also no levies are imposed on the River Rhine, which includes

the bulk of inland navigation in the EU. Similarly, aviation is exempt from

excise duties and VAT.

Finally, another important issue in considering the

policy of internalisation is the role of public transport subsidies. In the

short term, before full internalisation has been achieved, subsidies can provide

another way of promoting less environmentally harmful transport modes. Some

governments subsidise passenger train services in order to provide an alternative

to car transport and to help ensure social equity.

|

Box-5.3: Peak car reference prices and costs

In the TRENEN II STRAN research project urban and interregional models

were developed to assess pricing reform in transportation in the European

Union. The models were applied in six urban case studies and three interregional

case studies.

Although some methodological and data problems remain, the project findings

shows that the discrepancy between current prices and external costs in

congested urban conditions are often considerable. Figure 5.10 gives,

for some of the case studies and for 2005, the expected generalised prices

and marginal social costs of a small petrol car driven in the peak period

by a lone inhabitant who does not pay for his parking at destination.

The figure shows that peak car use covers only one-third to half of its

full marginal costs. There are two main sources of error: unpaid parking

and the omission of some external congestion costs (e.g. the time costs

that each user imposes on others). Unpaid parking distorts prices in the

peak and off-peak. Its importance varies across cities: parking costs

are much higher in London and Amsterdam than in Brussels and Dublin. The

external costs shown in the figures cover congestion air pollution, accidents

and noise.

In the inter-urban passenger transport case studies (results for Belgium

and Ireland in the figure), the difference between current taxes and charges

and external costs were found to be less important than for urban transport.

Figure 5.10: Peak car reference prices and costs (expected situation

for 2005 with unchanged pricing policies)

Source: TRENEN II STRAN ST 96 SC 116 - Final Summary Report

Note: The generalised price (left block for each city/country)

includes the resource costs (except parking), taxes and own-time costs.

The generalised marginal social cost (right block) includes resource costs,

parking resource costs, own-time costs and marginal external costs.

|

Future work

- Problems in analytical method and data shortcomings

make estimates of external costs and the degree of internalisation uncertain.

These must be overcome to improve this indicator.

- The environmental costs of water and soil pollution,

vehicle production and disposal pollution, effects on ecosystems, visual annoyance

and splitting communities with transport infrastructure are inadequately covered

and methods of estimating them need to be improved.

- The estimates for climate change include many uncertainties

and do not allow for NOx and CO2 emissions from aircraft.

The external costs of aviation are therefore underestimated.

- The environmental impacts of maritime shipping are

not included because of gaps in data and definition problems.

- An update of the IWW/INFRAS study (UIC, 1994) is

being prepared to improve understanding of the magnitude of external costs

in Member States.

- The European Commission has outlined plans to develop

methods of calculating the external and internal costs of transport (CEC,

1998d).

- At present, data on subsidies (i.e. TERM Indicator

17) is not collected in a way that enables an EU-wide indicator to be quantified.

Such an indicator is likely to show wide variations in subsidy policy and

level across the EU.

|

Data

Proportion of external and infrastructure costs covered by revenues in

transport, 1991

Unit: million ECU for cost data and %

for recovery rate

|

| |

External costs

|

Infrastructure costs

|

Total costs

|

Revenues

|

Cost recovery

rate (%)

|

| |

road

|

rail

|

road

|

rail

|

road

|

rail

|

road

|

rail

|

road

|

rail

|

|

Austria

|

6 665

|

112

|

3 713

|

1 283

|

10 378

|

1 395

|

2 613

|

729

|

25.2

|

52.3

|

|

Belgium

|

8 680

|

126

|

1 152

|

600

|

9 832

|

726

|

664

|

351

|

6.8

|

48.3

|

|

Denmark

|

3 424

|

120

|

1 338

|

171

|

4 762

|

291

|

2 467

|

90

|

51.8

|

30.9

|

|

Finland

|

3 208

|

94

|

3 068

|

283

|

6 276

|

377

|

1 829

|

46

|

29.1

|

12.2

|

|

France

|

34 998

|

335

|

22 853

|

4 265

|

57 851

|

4 600

|

19 407

|

2 604

|

33.6

|

56.6

|

|

Germany

|

61 846

|

1 445

|

25 049

|

4 724

|

86 895

|

6 169

|

22 583

|

2 008

|

26.0

|

32.5

|

|

Greece

|

3 240

|

29

|

687

|

112

|

3 927

|

141

|

756

|

65

|

19.3

|

46.1

|

|

Ireland

|

1 572

|

35

|

800

|

48

|

2 372

|

83

|

955

|

28

|

40.3

|

33.7

|

|

Italy

|

34 795

|

832

|

20 649

|

2 439

|

55 444

|

3 271

|

22 288

|

1 424

|

40.2

|

43.5

|

|

Luxembourg

|

340

|

9

|

284

|

28

|

624

|

37

|

149

|

16

|

23.9

|

43.2

|

|

Netherlands

|

7 829

|

139

|

4 142

|

522

|

11 971

|

661

|

4 920

|

305

|

41.1

|

46.1

|

|

Portugal

|

5 445

|

118

|

676

|

133

|

6 121

|

251

|

590

|

78

|

9.6

|

31.1

|

|

Spain

|

20 702

|

293

|

7 082

|

1 718

|

27 784

|

2 011

|

5 934

|

1 003

|

21.4

|

49.9

|

|

Sweden

|

5 527

|

69

|

2 947

|

5 216

|

8 474

|

5 285

|

5 047

|

690

|

47.9

|

13.1

|

|

United Kingdom

|

38 508

|

538

|

13 142

|

2 132

|

51 650

|

2 670

|

19 750

|

1 245

|

38.2

|

46.6

|

|

EU15

|

236 779

|

4 294

|

107 582

|

25 255

|

344 361

|

29 549

|

109 952

|

10 682

|

30.3

|

39.1

|

Note: external

costs include cost of accidents

Source: EEA, 1999 using data from UIC, 1994 and ECMT, 1998 |

Document Actions

Share with others