Water — from rivers and lakes to wetlands and seas — is home to many animals and plants and countless more depend on it. For people, water bodies are sources of health, food, income and energy, as well as major transport pathways and places for recreation.

For centuries, humans have altered European water bodies to grow food, produce energy and protect against flooding. These activities have been central to Europe’s economic and social development, but they have also harmed water quality and the natural habitats of fish and other water life, especially in rivers. In many cases, water also has the unfortunate task of transporting the pollution we emit to air, land and water, and, in some cases, it is also the final destination of our waste and chemicals.

In short, we have been quite efficient at reaping the benefits of water, but this has come at a cost to the natural environment and to the economy. Many water ecosystems and species are under threat: many fish populations are in decline, too much or too little sediment reaches the sea, coastal erosion is on the increase, and so on. In the end, all these changes will also have an impact on the seemingly free services that water bodies currently provide for people.

Europe’s lakes, rivers and coastal waters remain under pressure

Pollution, over-abstraction and physical alterations — such as dams and straightening — continue to harm freshwater bodies across Europe. These pressures often have a combined effect on water ecosystems, contributing to biodiversity loss and threatening the benefits that people receive from water.

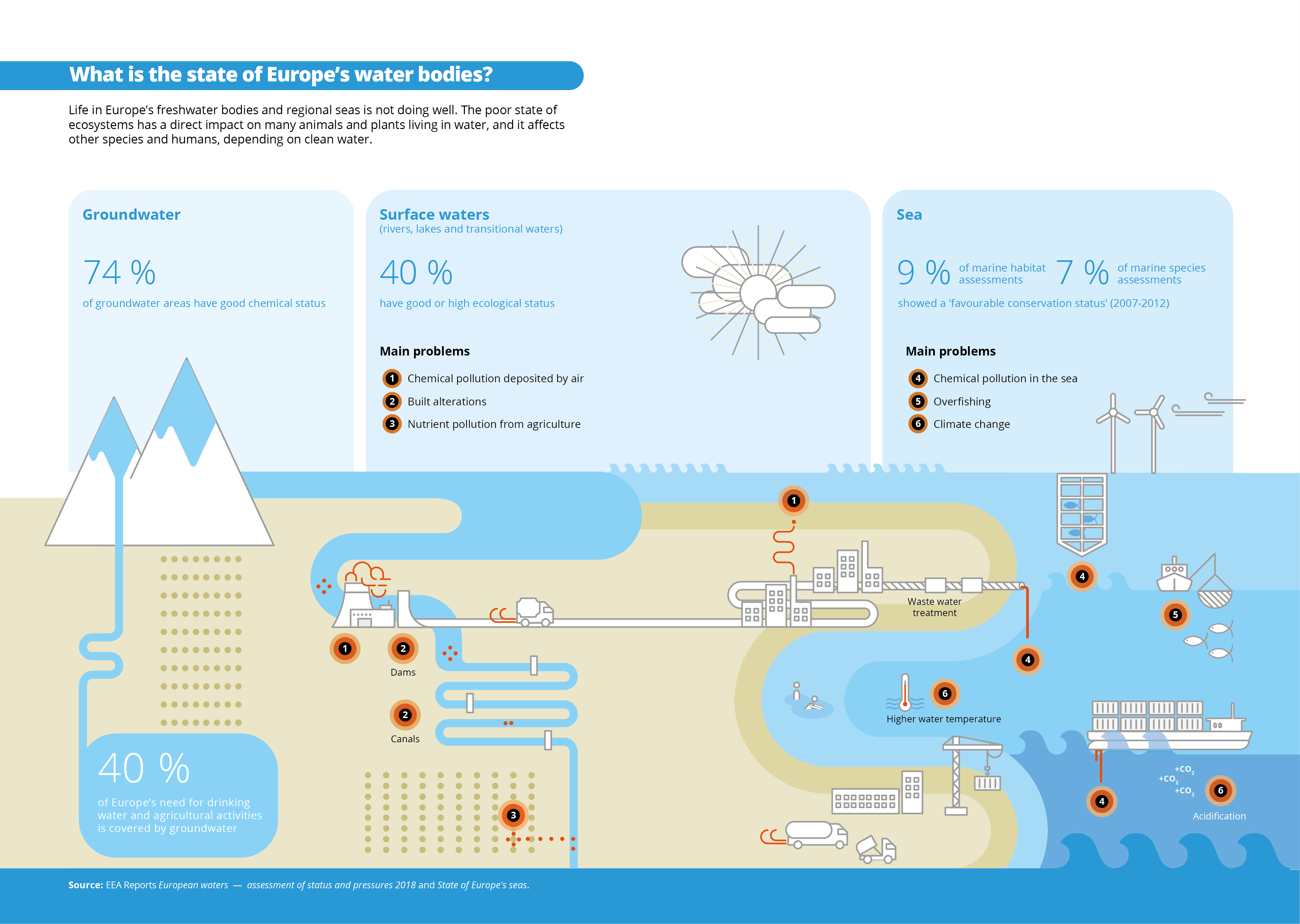

According to the EEA’s recent report, European waters — assessment of status and pressures 2018, only 39 % of surface waters achieve good or high ecological status. Generally, rivers and transitional waters that lead to a marine environment (e.g. delta areas) are in a worse state than lakes and coastal waters. The ecological status of natural water bodies is generally better than the status of heavily altered and artificial water bodies, such as reservoirs, canals and ports.

On the positive side, Europe’s groundwaters, which in many countries provide 80-100 % of drinking water, are generally clean, with 74 % of groundwater areas achieving good chemical status.

The main problems in surface water bodies include excessive nutrient pollution from agriculture, chemical pollution deposited from the air and built alterations that degrade or destroy habitats, especially for fish.

Intensive agriculture relies on synthetic fertilisers to increase crop yields. These fertilisers often work by introducing nitrogen and other chemical compounds into the soil. Nitrogen is a chemical element abundant in nature and essential for plant growth. However, some of the nitrogen intended for crops is not taken up by plants. This could be for a number reasons, such as the amount of fertiliser applied is more than the plant can absorb or it is not applied during the plant’s growing period. This excess nitrogen finds its way to water bodies.

Similar to its impacts on land-based crops, excess nitrogen in water boosts the growth of certain water plants and algae in a process known as eutrophication. This extra growth depletes the oxygen in water to the detriment of other species living in that water body. Agriculture, however, is not the only source of nitrogen ending up in water. Industrial facilities or vehicles running on diesel can also release significant amounts of nitrogen compounds into the atmosphere, which are later deposited on land and water surfaces.

Emissions of heavy metals from industry to water are decreasing rapidly, according to a recent EEA analysis of the data in the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR). The analysis found that environmental pressures caused by industrial emissions of eight key heavy metals ([1]) to water decreased by 34 % from 2010 to 2016. Mining activities accounted for 19 % and intensive aquaculture for 14 % of those pressures. In intensive aquaculture, copper and zinc leak to the sea from fish cages, in which the metals are used to protect them from corrosion and growth of marine organisms. The harmful effects of heavy metals may include, for example, learning, behavioural and fertility problems in animals and humans.

Other sources of pollution are also emerging. For example, in recent years, pollution from pharmaceutical products, such as antibiotics and anti-depressants, has been increasingly detected in water and is impacting aquatic species’ hormones and behaviour.

Action taken but a time delay at play?

The dire state of water bodies has not improved over the last decade, despite efforts by EU Member States, including tackling sources of pollution, restoring natural habitats and installing fish passes around dams. Considering that an impressive number of dams and reservoirs are built on European rivers, the scale of the measures taken may be too small to bring about a significant improvement. It is also possible that there is a time delay and that some of these measures will result in tangible improvements in the longer term.

One positive indication that we can see already is the clear progress made in treating urban waste water and reducing sewage emitted to the environment.Concentrations of pollutants linked to waste water discharge, such as ammonium and phosphate, in European rivers and lakes have decreased markedly over the past 25 years. An EEA indicator on urban waste water treatment also shows continued improvement in both the coverage and the quality of treatment in all parts of Europe.

Wetlands under pressure

Along with dunes and grasslands, wetlands are one of the most threatened ecosystems in Europe. Wetlands, including mires, bogs and fens, play a crucial role as the meeting point of water and land habitats. A rich variety of species live in and depend on wetlands. They also purify water, offer protection against floods and droughts, provide key staple foods such as rice, and protect coastal zones against erosion.

Largely due to land drainage, Europe lost two thirds of its wetlands between 1900 and the mid-1980s. Today wetlands comprise only about 2 % of the EU’s territory and about 5 % of the total Natura 2000 area. Although most wetland habitat types are protected in the EU, the conservation status assessments show that 85 % have an unfavourable status, with 34 % in poor and 51 % in bad status.

Europe’s seas are productive but not healthy or clean

Europe’s seas are home to a wide variety of marine organisms and ecosystems. They are also an important source of food, raw materials and energy.

The EEA report State of Europe’s seas found that Europe’s marine biodiversity is deteriorating. Of those marine species and habitats that were assessed from 2007 to 2012, only 9 % of habitats and 7 % of species showed a ‘favourable conservation status’. Moreover, marine biodiversity remains insufficiently assessed, as about four in five species and habitat assessments under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive are categorised as ‘unknown’.

Overfishing, chemical pollution and climate change are among the main reasons for the poor state of ecosystems in Europe’s seas. A combination of these three pressures has led to major changes in all four of Europe’s regional seas: the Baltic Sea, the North-East Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. Often, clear waters with a variety of fish and fauna have been replaced by algae and phytoplankton blooms and small, plankton-eating fish. This loss of biodiversity affects the entire marine ecosystem and the benefits it provides.

Invasive alien species, moving to Europe’s seas as a result of climate change and the expansion of maritime transport routes, are another major threat to marine biodiversity. In the absence of their natural predators, alien species’ populations can expand rapidly to the detriment of local species and they can cause irreversible harm. As in the case of the comb jellyfish, introduced into the Black Sea through ships’ ballast water, invasive alien species can even cause the collapse of certain fish populations and the economic activities dependent on those stocks.

Despite these major challenges, however, marine ecosystems have so far shown great resilience. Only a few European marine species are known to be extinct and, for example, the overfishing of assessed stocks in the North-East Atlantic Ocean fell substantially from 94 % in 2007 to 41 % in 2014. In some areas, individual species, such as the bluefin tuna, show signs of recovery, and some ecosystems are starting to recover from the impacts of eutrophication.

Similarly, an increasing proportion of Europe’s seas has been designated as marine protected areas in recent years. In fact, by the end of 2016, the EU Member States had designated 10.8 % of their marine areas as part of a network of marine protected areas, confirming that the EU has already achieved the target of 10 % coverage by 2020 (Aichi target 11) agreed under the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010.

Despite such improvements, the EEA report on the state of Europe’s seas concludes that European marine ecosystems maintain some resilience, and bringing back healthy marine life is still possible with the right interventions. This, however, will take decades and can only happen if the pressures that currently threaten marine animals and plants are considerably reduced.

Strong EU policies but implementation falls short

The main aim of the European Union’s (EU) water policy has been to ensure a sufficient quantity of good-quality water available to satisfy the needs of people and the environment. In this context, the key piece of EU legislation, the Water Framework Directive, required all EU Member States to achieve good status in all surface and groundwater bodies by 2015, unless there were grounds for exemption such as natural conditions and disproportionate costs. Depending on the reason, the deadlines may have been extended or Member States may be allowed to achieve less stringent objectives.

Achieving ‘good status’ requires meeting all three standards for ecology, chemistry and quantity of waters. In general, it means that water shows only a slight change from what might be expected under undisturbed conditions. Until now, Member States have not achieved this goal in most of their surface and ground waters.

Through its Birds and Habitats Directives (often referred to as the nature directives), the EU protects its most endangered species and habitats and all wild birds. In this context, a number of measures, including the Natura 2000 network of protected areas, are put in place to prevent or minimise impacts on the species and habitats covered by these EU directives. Although it covers a significant proportion of Europe’s seas, the marine Natura 2000 network is still not entirely complete and many sites lack appropriate conservation measures.

To achieve greater coherence among marine-related policies and to protect the marine environment more effectively, in 2008 EU Member States agreed on the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive. The Directive has three main goals: Europe’s seas should be (1) healthy, (2) clean and (3) productive. According to the EEA’s assessment, Europe’s seas are not healthy or clean and it is not clear how long they can remain productive.

Recognising this situation, the European Commission’s Action plan for nature, people and the economy, published in April 2017, aims to significantly improve the implementation of the nature directives and the actions under the plan are expected to directly contribute to marine conservation initiatives.

[1] The EEA briefing assesses emissions of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel and zinc.