Based on a

simulation, cutting motorway speed limits from 120 to 110 km/h could deliver

fuel savings for current technology passenger cars of 12–18 %, assuming smooth

driving and 100 % compliance with speed limits. However, relaxing these

assumptions to a more realistic setting implies a saving of just 2–3 %.

Significant fuel

savings can be achieved by encouraging drivers to maintain a consistent speed

and restrict their speed (eco-driving), including through effective enforcement

of speed limits.

Cutting speed can also significantly reduce

emissions of other pollutants, particularly reducing NOx and

particulate matter (PM) output from diesel vehicles. The safety gains from

slower driving are also indisputable.

Transport: a major

contributor to greenhouse gas emissions

Transport is the only sector whose greenhouse emissions increased between

1990 and 2008. Transport’s total GHG output rose 25 % in the 32 EEA member

countries (this excludes the international maritime and aviation sectors), accounting

for 19.5 % of total emissions. CO2 is the main component of

transport greenhouse gas emissions (99 %) and road transport is, in turn,

the largest contributor to these emissions (around 94 % in 2008), thus

accounting for 18.2% of total emissions.

New vehicles are, on average, more energy efficient than older

vehicles, and the improvement will increase as a result of recent

EU regulation on cars and CO2 and the agreement

on similar legislation for light commercial vehicles. However, full fleet

penetration of new technologies takes almost two decades. Moreover, impacts will

also be offset by the likely growth in transport volumes. As such, other

measures must also be considered to achieve short-term improvements in GHG emissions

and energy consumption.

It is also worth noting in this context that, because CO2

emissions are directly linked to fuel consumption, measures designed to reduce

GHG emissions from transport would also help reduce dependence on oil imports.

Targets set recently in EU papers and strategies, such as the Roadmap

for a low carbon economy and the recently published White

paper on Transport, encourage implementation of such measures.

The idea of using more stringent speed limits to reduce travelling

speeds on motorways and thereby cut fuel consumption and transport emissions has

received much attention recently. Among all the potential measures available,

stricter speed limits could have an immediate effect on fuel consumption and

emissions. Scientific evidence and knowledge sharing could help make lower

speed limits more politically acceptable by clarifying the environmental

consequences, as well as the impacts on safety and mobility.

Current speed limits differ across EU Member States, and the competence

to define them generally lies with national governments. Some countries also

apply variable speed limits related to traffic and weather conditions. For

these reasons it is not possible to simulate the precise effects of a speed

limitation across all EU Member States. In addition, the actual fuel

consumption benefits of lower speed limits depend on factors such as the type

of cars using the motorways, driving patterns, the frequency of speeding, road

load patterns and congestion. Estimating the benefits is not straightforward

but this note aims to convey the main messages on the relationship between speed

and fuel consumption.

Simulating reduced speed

limits

Emission models are generally

used to assess the impact of speed management measures. COPERT is a robust

emission model widely used in Europe, with

COPERT 4 being its latest version. Its consumption factors are expressed as a

function of the mean travelling speed and have been obtained based on tests of

a variety of passenger cars and driving cycles.

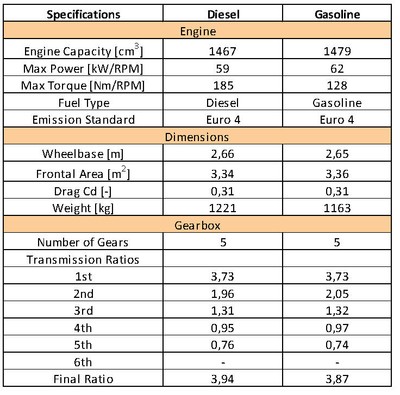

For the purposes of this

note, EMISIA ()

conducted a simulation of three driving cycles in order to simulate the fuel

consumption impact of reducing a motorway speed limit from 120 to 110 km/h. The

simulation used two medium class vehicles, representative of the typical diesel

and gasoline passenger cars used in European countries (1.4 litre Euro 4

emission standard, as presented in the annex).

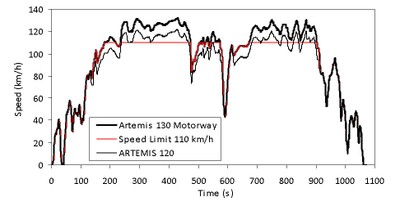

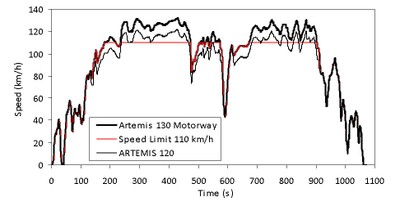

The three cycles simulate were

as follows:

- ARTEMIS 130: a typical driving cycle assuming a

speed limit of 120 km/h, which is not fully respected, meaning that some speeding

occurs.

- Speed limit 110 km/h: a driving cycle assuming that

all drivers fully respect the speed limit and that the vehicles are very

smoothly driven at the speed limit. This is an artificial condition but may

demonstrate the maximum potential results of introducing a new speed limit.

- ARTEMIS 120: similar assumptions to ARTEMIS 130 and

considering that the reduction of the speed limit from 120 km/h to 110 km/h

will also decrease cruise speed by 10 km/h. As the ARTEMIS 130 cycle, it is

assumed that the speed limit of 110 km/h is not fully respected and some speeding

occurs.

The three driving cycles

used in the simulation are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: speed profile of the driving cycles used in

the analysis

Source: EMISIA - ETC/ACM

Results and discussion

The simulation reveals that

shifting from the ARTEMIS 130 cycle to fully respecting the speed limit and

controlling the speed at 110 km/h would produce a significant drop in fuel

consumption — 12 % in the case of a diesel car and 18 % in the case

of a gasoline car.

However, shifting from

ARTEMIS 130 to the more ‘realistic’ ARTEMIS 120 cycle produces a much smaller reduction

of 2–3 %. This is mostly caused by the fact that when a car travels at a lower

average speed, the wind resistance decreases and therefore the car requires

less energy.

Table 1: Characteristic values for the three

driving cycles used

|

Driving pattern

|

Average speed (km/h)

|

Max speed (km/h)

|

Diesel

|

Gasoline

|

|

Fuel consumption (l/100 km)

|

|

ARTEMIS 130

|

97

|

132

|

8,0

|

9,6

|

|

Speed Limit 110

|

90

|

110

|

7,0

|

7,9

|

|

ARTEMIS 120

|

90

|

122

|

7,8

|

9,3

|

|

|

|

|

Reduction over ARTEMIS 130 (%)

|

|

Speed Limit 110

|

|

|

12

|

18

|

|

ARTEMIS 120

|

|

|

2

|

3

|

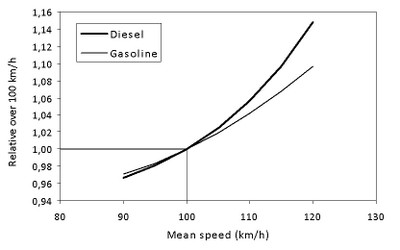

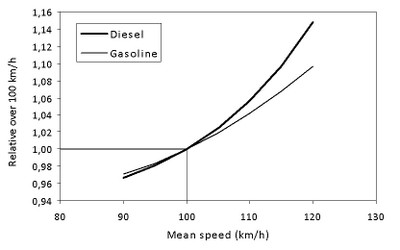

The simulation results shown in Table 1 demonstrate that fuel

consumption generally decreases with speed, although the exact benefits are context

specific. Figures 2, 3 and 4 likewise illustrate the link between average speed,

fuel consumption and pollutant emissions for Euro 4 diesel and gasoline cars with

engines of 1.4–2.0 litre capacity.

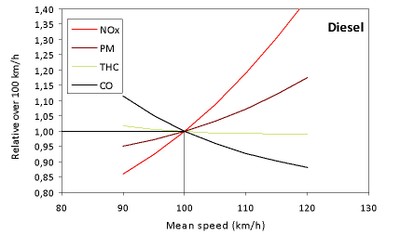

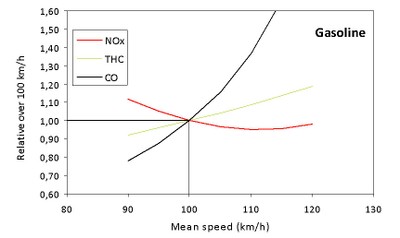

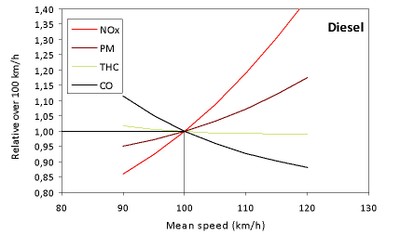

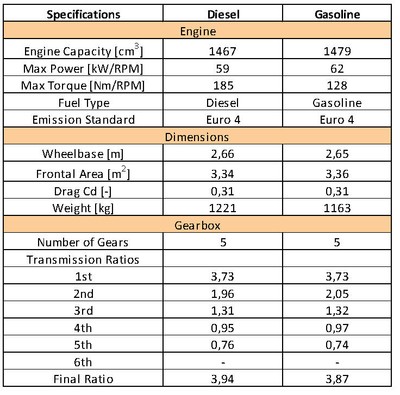

Figures 3 and 4 show that

reducing speed in the above range has a beneficial effect for all pollutants

except for CO (in the case of diesel vehicles) and NOx (in the case of gasoline

vehicles). The benefits of reducing average speed from 100 km/h to 90 km/h

range from 25 % (gasoline CO) to 5% (diesel PM). Crucially, decreasing

speed reduces the two pollutants currently most important in Europe:

diesel NOx and PM.

Figure 2: Impact

of travelling speed on fuel consumption (Euro 4 diesel and gasoline passenger

cars, 1.4–2.0 litre engine capacity)

Note: emissions expressed relative to their values at 100 km/h, for

which the value '1' is assigned.

Source: EMISIA - ETC/ACM

The rise in diesel CO and

gasoline NOx emissions at decreasing average speeds is largely due to

the operation of after-treatment devices. The diesel oxidation catalyst

operates more efficiently at high speed due to the higher temperature,

therefore oxidising carbon monoxide more effectively. Diesel vehicles are minor

contributors of CO, however, and CO is not a problem for air quality in Europe. As such, this impact of decreasing average speeds

would not cause problems.

For gasoline engines, increasing

speed up to approximately 115 km/h leads to lower NOx emissions,

although emissions increase again above that speed. Gasoline vehicles emit much

less NOx than diesel vehicles. According to COPERT, a gasoline Euro

4 car emits 19 mg/km NOx compared to 560 mg/km of a corresponding

diesel car at 100 km/h. Therefore, the overall effect on NOx of

reducing the speed on motorways would be positive because diesel NOx

is dominant and clearly drops with decreasing speed.

Figure 3: Impact

of travelling speed on various pollutants (Euro 4 diesel passenger cars,

1.4–2.0 litre engine capacity)

Note: emissions expressed relative to their values at 100 km/h, for

which the value '1' is assigned.

Source: EMISIA - ETC/ACM

NOx denotes ‘nitrogen oxides’; PM denotes ‘particulate

matter’; THC denotes ‘total hydrocarbons’; CO denotes ‘carbon monoxide’.

Figure 4: Impact of travelling speed on various

pollutants (Euro 4 gasoline passenger cars, 1.4–2.0 litre engine capacity)

Note: emissions expressed

relative to their values at 100 km/h, for which the value '1' is assigned.

Source: EMISIA - ETC/ACM

In summary, whereas heavy

goods vehicles speed limits in motorways are in line with the optimum speed in

terms of energy and CO2 reductions per vehicle-km (80–90 km/h),

decreasing car passenger speed limits in motorways could lead to substantial

benefits.

The modelling results also

suggest that speed limitations of 80–90 km/h on motorways when entering cities and

on city ring roads could significantly reduce both fuel consumption and

pollutants emitted, in addition to delivering safety benefits.

On the other hand, energy

and emissions benefits from more stringent speed limits on local roads (e.g. from

50 to 30 km/h) are less clear. The key argument for lower speeds on local roads

is therefore the desirability of a safer and more tranquil local environment,

rather than environmental considerations.

A new balance in setting

speed limits?

Setting a speed limit is

about balancing three core priorities: mobility, safety and the environment. Factors

such as Europe’s dependence on fuel imports,

concerns about sustained oil supplies and better environmental understanding

are encouraging governments to rethink their speed limit decisions and work to find

a new optimum balance.

Central to their

decision-making will be public willingness to change behaviour. Encouragingly, a

recent public poll (Flash Eurobarometer Report, no. 312, Future of Transport) indicates that about two

thirds of EU citizens are willing to compromise a car’s speed in order to

reduce emissions. The reality on the roads, however, appears to be quite

contradictory. Around 40–50 % of drivers (up to 80 % depending on the

country and type of roads) drive above legal speed limits ([2]).

This suggests that there is

clear value in providing citizens with a clear understanding of the benefits

and costs. After all, a speed limit decrease of 10 km/h in a motorway (from 120

to 110 km/h) would mean an extra travel time of just eight to nine minutes in a

200 km long trip, assuming perfect flow conditions. That is arguably a limited

price to pay in exchange for the fuel savings and environmental benefits. At

the same time, it seems clear that drivers’ theoretical support for lower

limits is insufficient — steps to improve compliance, including tighter

enforcement, will be essential to achieve concrete results.

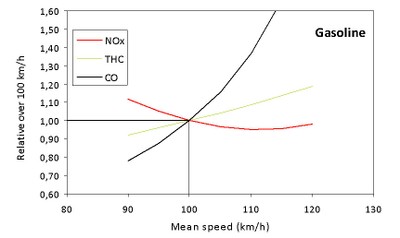

Annex

Specifications of cars used in the simulations

Current general speed limits in European countries

|

|

Motorways

|

Outside built-up areas

|

Built-up areas

|

|

Austria

|

130

|

100

|

50

|

|

Belgium

|

120

|

90-120

|

30-50

|

|

Bulgaria

|

130

|

90

|

50

|

|

Cyprus

|

100

|

80

|

50

|

|

Croatia

|

130

|

90-100

|

50

|

|

Czech Republic

|

130

|

90

|

50

|

|

Denmark

|

110-130

|

80

|

50

|

|

Estonia

|

110

|

90-110

|

50

|

|

Finland

|

100-120

|

80-100

|

40-50

|

|

France

|

110-130

|

80-110

|

50

|

|

Germany

|

-130

|

100

|

30-50

|

|

Greece

|

130

|

90-110

|

50

|

|

Hungary

|

130

|

90-110

|

50

|

|

Iceland

|

-

|

80-90

|

30-50

|

|

Ireland

|

120

|

80-100

|

50

|

|

Italy

|

130-150

|

90-110

|

50

|

|

Latvia

|

110

|

90

|

50

|

|

Lithuania

|

110-130

|

70-90

|

50

|

|

Luxembourg

|

130

|

90

|

50

|

|

Malta

|

-

|

60-80

|

50

|

|

Netherlands

|

100-120

|

80-100

|

30-50-70

|

|

Norway

|

90-100

|

80

|

30-50-70

|

|

Poland

|

130

|

90-110

|

50-60

|

|

Portugal

|

120

|

90-100

|

50

|

|

Romania

|

130

|

90-100

|

50

|

|

Slovakia

|

130

|

90

|

50

|

|

Slovenia

|

130

|

90-100

|

30-50

|

|

Spain

|

110

|

90-100

|

50

|

|

Sweden

|

100-120

|

70-90

|

30-50

|

|

Switzerland

|

120

|

80

|

30-50

|

|

Turkey

|

110-120

|

90

|

50

|

|

United

Kingdom

|

112

|

96-112

|

32-48

|

Source: DG TREN, 2010. Energy

and Transport Statistical Pocketbook.

Notes:

UK, IE, CY and MT

drive on the left hand side of the road, the other Member States drive on the

right hand side (SE since 3.9.1967).

Signs in UK are in miles per hour.

The higher figure shown in

the 'outside built-up areas' column generally refers to the speed limit on dual

carriageways that are not motorways.

Speed limits:

- Germany: Motorways: No

general speed limit, recommended speed limit is 130 km/h (more than half the

network has a speed limit of 120 km/h or less).

- France: Dual

carriageways 110 km/h. If road is wet: motorways 110 km/h, dual carriageways 90

km/h, other roads outside built-up areas 80 km/h.

- Spain: New motorway

speed limit from March 7th 2011

- Italy: 150 km/h on

certain 2x3 lane motorways.

- Finland: in winter 100

km/h on motorways, 80 km/h on other roads.

- Poland: Built-up areas: 50 km/h from 05h00 to 23h00,

60 km/h from 23h00 to 05h00.

- Turkey: Speed limit

recently changed to 110 km/h on dual carriageways and 120 km/h on motorways

()

EMISIA is part of the European

Topic Centre on Air Pollution and Climate change Mitigation (ETC/ACM).

() OECD-ECMT, 2006, Speed

management, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and European

Conference of Ministers of Transport.

Document Actions

Share with others