As a small island, Malta is arguably an entire coastal region with typical coastal issues such as high urbanisation rate, significant tourist sector, and vulnerability to the impacts of climate change all being key issues for Malta.[1] Marine areas are also very important for Malta, as most of its ‘territory’ is actually marine. Due to their geographical characteristics, limited area and intrinsic attractiveness, coastal and marine areas are under considerable pressure from various (often conflicting) human activities. These pressures are often exacerbated in the summer months when demand for coastal activity increases. Unfortunately, much of the development, as well as many activities taking place in coastal areas, tend to result in singular or limited uses. This increases competition for the use of such land.

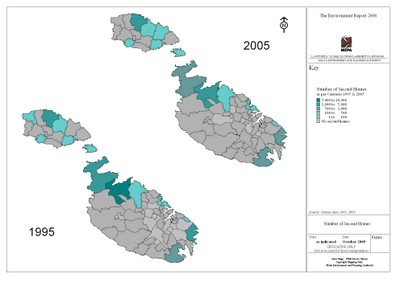

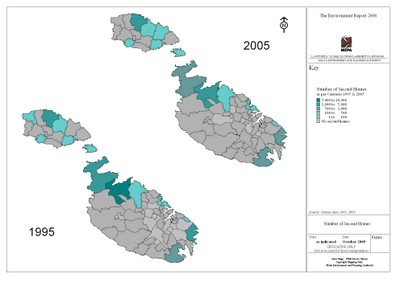

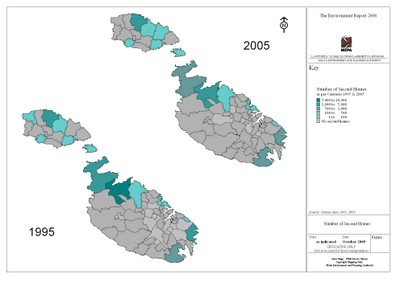

Pressure for coastal urbanisation has been considerable over the last decades. Indeed the highest population growth rates between the 1995 and 2005 censuses were in two seaside resort localities,[2] where growth exceeded 80 percent (Map 1). Tourism, including local tourism, is a major pressure in coastal and marine areas. It increases coastal populations, as well as pressure for hotel, holiday apartment and marina development. The number of second residences, the large majority of which are found in localities directly adjacent to the sea, and used by both foreign and local tourists, rose from 12,738 to 39,700 between 1995 and 2005. Marinas also contribute to coastal urbanisation and artificialisation. The number of yacht berths increased by 66 percent between 1995 and 2008, from 1,092 to 1,807.296 Tourism also gives rise to pressure on beaches, which are generally ecologically sensitive (and protected), in the form of increased littering and waste generation, illegal camping and construction of boat houses, as well as additional requests and permissions for beach concessions and the holding of public events. Nevertheless, where improved coordination between responsible agencies has taken place, there has been progress in beach management. EU-related opportunities in this respect are presented by the new Bathing Water Directive301 and the Blue Flag voluntary environmental scheme.300 Shipping constitutes the third major pressure on coastal and marine environments, and this activity involves both pollution-related and spatial impacts. Gross shipping tonnage reaching Maltese ports increased by almost 70 percent between 2000 and 2008.304

Source: COS 1998; NSO 2007a

Map 1: Percentage of second homes by locality

Other pressures on coastal and marine areas include fisheries and aquaculture, waste disposal306 and the emerging issue of climate change. The latter is expected to give rise to increased sea temperature and level, more storm surges resulting in coastal floods, changes in alkalinity and salinity and increased pollution from freshwater and land-based pollutant run-off. Since most of the important coastal habitats and recreational spaces on the Maltese coast are low-lying, any rise in sea level or increases in storm surges are likely to impact these areas, principally through erosion.

EU environmental policy has provided a major boost to Malta’s policy and practice in the coastal and marine policy area, being highly supportive of national processes relating to key issues such as bathing water quality, nature protection and urban wastewater treatment. Bathing water quality is a key indicator of coastal water quality, with importance for health, recreation and tourism. Malta is obliged to achieve water quality standards under the Bathing Water Directive,313 and the UN Barcelona Convention, which Malta has been a signatory to since its inception in 1976.314 Compliance with mandatory bathing water standards increased considerably between 2005 and 2008, such that in 2008 Malta’s bathing waters reached 99 percent compliance, exceeding the average compliance rate of 95.7% in Mediterranean EU Member States that year. Compliance with more stringent guide values increased to 94 percent in 2008. In terms of the Barcelona Convention, 100 percent of sites classified as (guideline and more stringent) Class One or as the mandatory Class Two. The number of Class One sites increased by almost 30 percent between 2005 and 2008.

With respect to nature protection, and in accordance to the EU Habitats Directive and various multi-lateral environmental agreements, Malta has designated and taken steps to manage protected sites covering land and marine areas of ecological importance. As of end 2008, Malta has designated two Marine Protected Areas. One is the marine area between Rdum Majjiesa and Ras ir-Raheb on the North-West coast of Malta, which also[4] forms part of the Natura 2000 network and the other is located in the limits of Dwejra, Gozo. The two sites cover 11km2 of territorial waters. The designations of the various Natura 2000 sites (a significant amount of which are coastal) will yield results once further management measures are in place. EU structural funds will be allocated to address various management plans for Natura 2000 sites. Focus is now being given to the designation of further marine areas, and the necessary additional baseline surveys in this respect. (It should be noted that Malta designated four new marine sites in 2010). This is essential so as to afford protection to habitats and species of ecological importance. Another designation relates to the 25 nautical mile radius around the Maltese Islands, known as the Fisheries Conservation Zone, which followed EU accession in 2004. Management of this sea area is undertaken by limiting the number, size and power of fishing vessels allowed in the zone, depending on the type of fishing activities in which they are engaged.

In order to improve coastal water quality in the Maltese islands, new sewage treatment plants according to the requirements of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive are also being constructed. While two plants are already in operation, the Malta South sewage treatment plant is planned to be operational in 2010.[7] Once all three sewage treatment plants are in operation, all waste water generated in the islands will be treated up to the secondary stage and treatment will also result in the production of water that can potentially be re-used.

One area where Malta has historically faced challenges relates to environmental monitoring, particularly in relation to coastal and marine waters. Nevertheless, with the assistance of structural funding, Malta is investing heavily in setting up an environmental monitoring project that will ensure compliance with the monitoring requirements of the Water Framework Directive and eventually also support the implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Coastal and marine monitoring programmes are being revised within the context of a sector-wide structural funds project aimed at setting in place a comprehensive environmental monitoring programme for air, soil and water.

There are certain policy areas where Malta’s particular small island state situation has provided interesting opportunities for synergy between different environmental management tools. Coastal management is a case in point. The EU Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Recommendation obliges Malta to prepare a national ICZM strategy. Malta will fulfil this requirement through the land-use planning system. Malta has been addressing the management of the coast through its land-use planning system since the early 1990s. The 2002 Coastal Strategy Topic Paper, prepared as part of the Structure Plan Review process, provided planning guidance on how the land-use planning system can address coastal areas more effectively. This approach has been taken up in the Local Plan formulation process where a number of policies provide direction for coastal uses in line with the principles of ICZM and indicate which areas of the coast are to be protected from construction/development. The Replacement Structure Plan will take on board the proposals of the 2002 Coastal Strategy Topic Paper, and will provide a strategic policy framework for planning and development in coastal and marine areas for the next 20 years.

In addition to this positive step within the land-use planning system, the principles of ICZM have also been incorporated in the draft Water Catchment Management Plan (as required by the Water Framework Directive) which has targeted the integration of actions amongst the different regulatory bodies affecting the coastal waters in its program of measures.

With respect to marine areas, Malta will also need to prepare, in cooperation with neighbouring Member States, a national marine strategy by 2016 according to the requirements of the proposed European Marine Strategy Directive.[10]

Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31992L0043:EN:html, accessed on 6th November 2009), transposed by LN 311 of 2006 under the Environment Protection Act (Cap. 435) and the Development Planning Act (Cap. 356) (Flora, Fauna and Natural Habitats Protection Regulations, 2006), and amended by LN 162 of 2009.

GN 1138 of 2005 under the Environment Protection Act (Cap. 435) (Flora, Fauna and Natural Habitats Protection Regulations, 2003).

Water Services Corporation.

Pressure for coastal urbanisation has been considerable over the last decades. Indeed the highest population growth rates between the 1995 and 2005 censuses were in two seaside resort localities,[2] where growth exceeded 80 percent (Map 1). Tourism, including local tourism, is a major pressure in coastal and marine areas. It increases coastal populations, as well as pressure for hotel, holiday apartment and marina development. The number of second residences, the large majority of which are found in localities directly adjacent to the sea, and used by both foreign and local tourists, rose from 12,738 to 39,700 between 1995 and 2005. Marinas also contribute to coastal urbanisation and artificialisation. The number of yacht berths increased by 66 percent between 1995 and 2008, from 1,092 to 1,807.296 Tourism also gives rise to pressure on beaches, which are generally ecologically sensitive (and protected), in the form of increased littering and waste generation, illegal camping and construction of boat houses, as well as additional requests and permissions for beach concessions and the holding of public events. Nevertheless, where improved coordination between responsible agencies has taken place, there has been progress in beach management. EU-related opportunities in this respect are presented by the new Bathing Water Directive301 and the Blue Flag voluntary environmental scheme.300 Shipping constitutes the third major pressure on coastal and marine environments, and this activity involves both pollution-related and spatial impacts. Gross shipping tonnage reaching Maltese ports increased by almost 70 percent between 2000 and 2008.304

Source: COS 1998; NSO 2007a

Map 1: Percentage of second homes by locality

Other pressures on coastal and marine areas include fisheries and aquaculture, waste disposal306 and the emerging issue of climate change. The latter is expected to give rise to increased sea temperature and level, more storm surges resulting in coastal floods, changes in alkalinity and salinity and increased pollution from freshwater and land-based pollutant run-off. Since most of the important coastal habitats and recreational spaces on the Maltese coast are low-lying, any rise in sea level or increases in storm surges are likely to impact these areas, principally through erosion.

EU environmental policy has provided a major boost to Malta’s policy and practice in the coastal and marine policy area, being highly supportive of national processes relating to key issues such as bathing water quality, nature protection and urban wastewater treatment. Bathing water quality is a key indicator of coastal water quality, with importance for health, recreation and tourism. Malta is obliged to achieve water quality standards under the Bathing Water Directive,313 and the UN Barcelona Convention, which Malta has been a signatory to since its inception in 1976.314 Compliance with mandatory bathing water standards increased considerably between 2005 and 2008, such that in 2008 Malta’s bathing waters reached 99 percent compliance, exceeding the average compliance rate of 95.7% in Mediterranean EU Member States that year. Compliance with more stringent guide values increased to 94 percent in 2008. In terms of the Barcelona Convention, 100 percent of sites classified as (guideline and more stringent) Class One or as the mandatory Class Two. The number of Class One sites increased by almost 30 percent between 2005 and 2008.

With respect to nature protection, and in accordance to the EU Habitats Directive and various multi-lateral environmental agreements, Malta has designated and taken steps to manage protected sites covering land and marine areas of ecological importance. As of end 2008, Malta has designated two Marine Protected Areas. One is the marine area between Rdum Majjiesa and Ras ir-Raheb on the North-West coast of Malta, which also[4] forms part of the Natura 2000 network and the other is located in the limits of Dwejra, Gozo. The two sites cover 11km2 of territorial waters. The designations of the various Natura 2000 sites (a significant amount of which are coastal) will yield results once further management measures are in place. EU structural funds will be allocated to address various management plans for Natura 2000 sites. Focus is now being given to the designation of further marine areas, and the necessary additional baseline surveys in this respect. (It should be noted that Malta designated four new marine sites in 2010). This is essential so as to afford protection to habitats and species of ecological importance. Another designation relates to the 25 nautical mile radius around the Maltese Islands, known as the Fisheries Conservation Zone, which followed EU accession in 2004. Management of this sea area is undertaken by limiting the number, size and power of fishing vessels allowed in the zone, depending on the type of fishing activities in which they are engaged.

In order to improve coastal water quality in the Maltese islands, new sewage treatment plants according to the requirements of the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive are also being constructed. While two plants are already in operation, the Malta South sewage treatment plant is planned to be operational in 2010.[7] Once all three sewage treatment plants are in operation, all waste water generated in the islands will be treated up to the secondary stage and treatment will also result in the production of water that can potentially be re-used.

One area where Malta has historically faced challenges relates to environmental monitoring, particularly in relation to coastal and marine waters. Nevertheless, with the assistance of structural funding, Malta is investing heavily in setting up an environmental monitoring project that will ensure compliance with the monitoring requirements of the Water Framework Directive and eventually also support the implementation of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Coastal and marine monitoring programmes are being revised within the context of a sector-wide structural funds project aimed at setting in place a comprehensive environmental monitoring programme for air, soil and water.

There are certain policy areas where Malta’s particular small island state situation has provided interesting opportunities for synergy between different environmental management tools. Coastal management is a case in point. The EU Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) Recommendation obliges Malta to prepare a national ICZM strategy. Malta will fulfil this requirement through the land-use planning system. Malta has been addressing the management of the coast through its land-use planning system since the early 1990s. The 2002 Coastal Strategy Topic Paper, prepared as part of the Structure Plan Review process, provided planning guidance on how the land-use planning system can address coastal areas more effectively. This approach has been taken up in the Local Plan formulation process where a number of policies provide direction for coastal uses in line with the principles of ICZM and indicate which areas of the coast are to be protected from construction/development. The Replacement Structure Plan will take on board the proposals of the 2002 Coastal Strategy Topic Paper, and will provide a strategic policy framework for planning and development in coastal and marine areas for the next 20 years.

In addition to this positive step within the land-use planning system, the principles of ICZM have also been incorporated in the draft Water Catchment Management Plan (as required by the Water Framework Directive) which has targeted the integration of actions amongst the different regulatory bodies affecting the coastal waters in its program of measures.

With respect to marine areas, Malta will also need to prepare, in cooperation with neighbouring Member States, a national marine strategy by 2016 according to the requirements of the proposed European Marine Strategy Directive.[10]

Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31992L0043:EN:html, accessed on 6th November 2009), transposed by LN 311 of 2006 under the Environment Protection Act (Cap. 435) and the Development Planning Act (Cap. 356) (Flora, Fauna and Natural Habitats Protection Regulations, 2006), and amended by LN 162 of 2009.

GN 1138 of 2005 under the Environment Protection Act (Cap. 435) (Flora, Fauna and Natural Habitats Protection Regulations, 2003).

Water Services Corporation.

Document Actions

Share with others