Rejecting consumerism

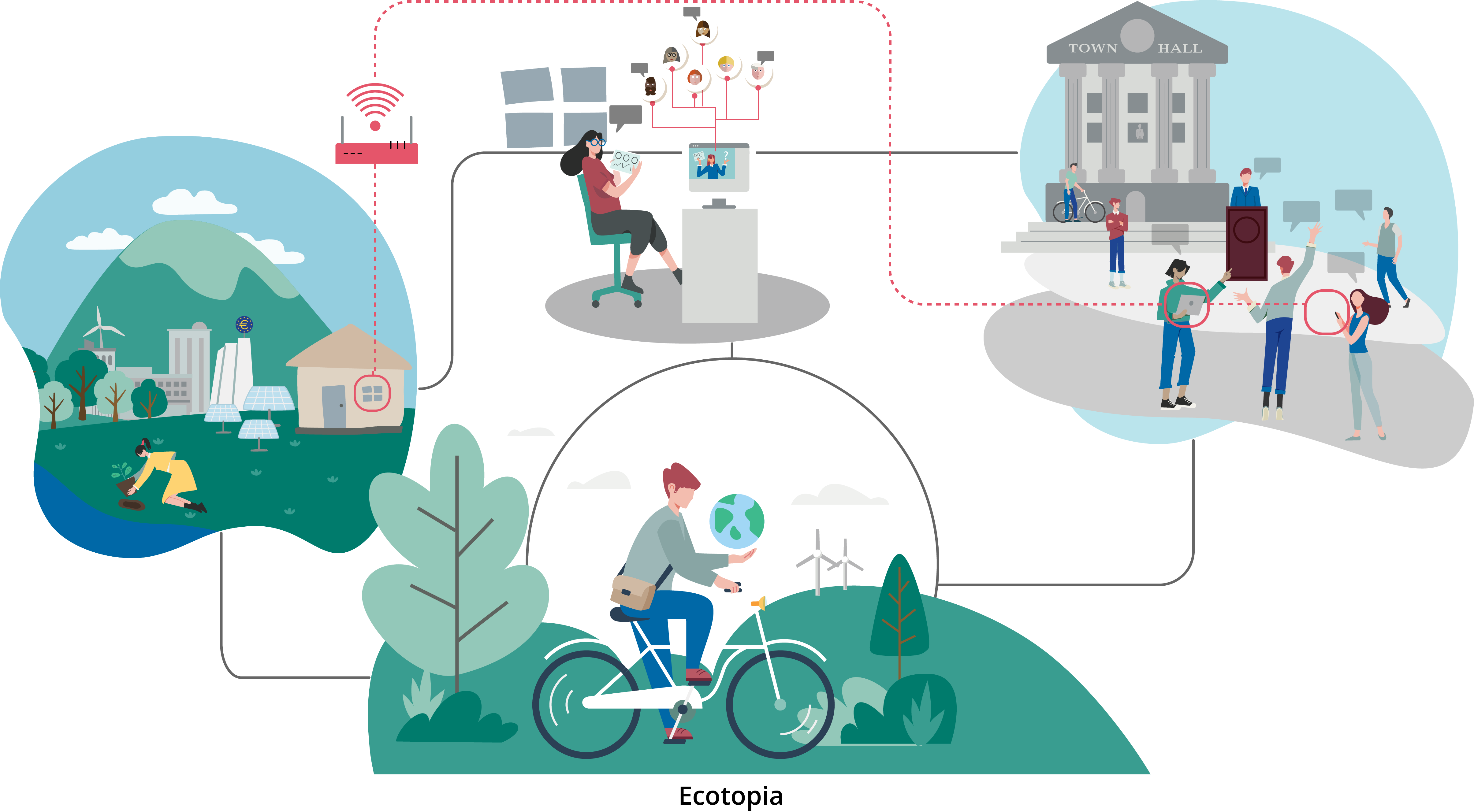

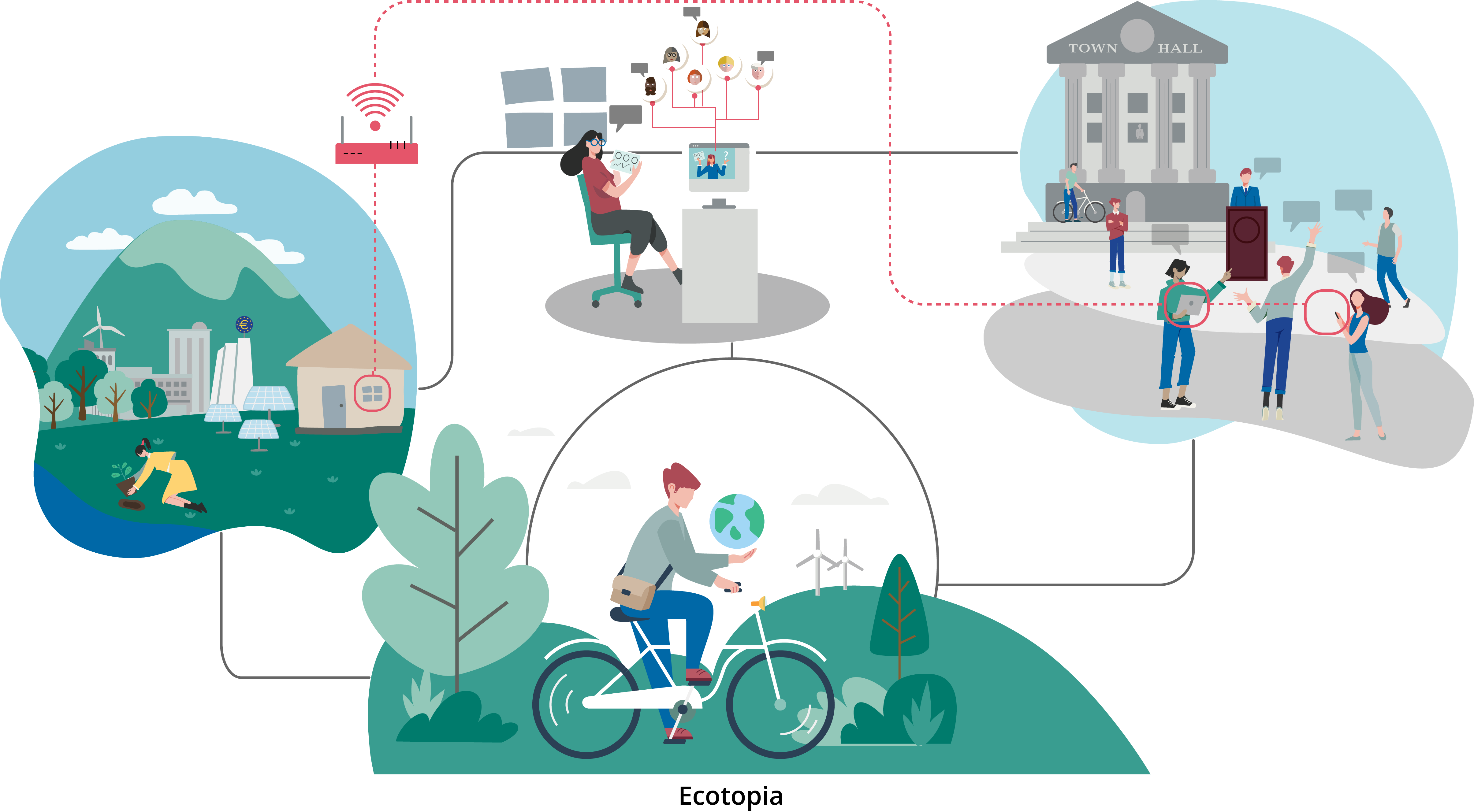

By 2050, Europe has undergone a profound socio-political and economic shift, reversing some of the societal changes of past centuries. This change in mentality has partly been driven by the impact of climate change, with weather extremes and disasters affecting large parts of the population, and the wish of the younger generations to live at peace with nature.

But some researchers also argue that the Ukraine war and its aftermath contributed to the emergence of a counterculture (a little like in the 1960s), which emphasised the capacity to live a good life in times of hardship, in preference to consumerism. Consequently, markets and centralised national governments are no longer so dominant in shaping collective thinking and action. Power has shifted to local communities and civil society organisations.

This profound shift should be understood in the context of an equally profound generational change. The ‘Greta and post-Greta generations’ developed a deep scepticism about market-driven or ‘liberal’ economic models and about strong central states and their ability to stop climate change. Profit maximisation and conspicuous consumption, according to their credo, should be replaced by sufficiency, equity and respect for nature. The new generations favour sharing and collaboration over competition, especially at local and regional levels.

Empowered by social media, young people have become much more engaged politically, balancing the influence of the large constituency of elderly voters. Public pressure — with the incessant activity of powerful non-governmental organisations — has forced companies to rethink their business models and to really implement corporate social responsibility. As a result of more frugal lifestyles, the consumption of a broad variety of goods declined. Consequently, economic output and finally resource use were scaled back.

Growing role for civil society

The full impact of this shift hit governments in the late 2030s. Reduced economic output implied a reduction in the fiscal resources available to central governments. This contributed to a reduction in the state’s capacities and roles, including its ability to finance public health and welfare expenditure. While this has created challenges, it also created space for civil society and grassroots initiatives to play a more important role in devising and delivering novel ways of providing care and support. Family ties and neighbourhoods regained importance, in keeping with the mentality of the younger generations. With the spread of ‘repair and exchange cafés’, old crafts have been revived.

Social and cultural innovations (such as these cafés) often have more impact on society and the economy than new technologies, although there are many exceptions. For example, information and communication technologies are important in engaging communities and enabling individuals to help each other via non-market transactions. Paradoxically, the nature-loving youngsters spend a large part of their time in the digital sphere.

By 2050, families have benefited from reduced working hours and work-life balance is no longer an issue. Stress-induced mental disorders have nearly vanished, although even volunteers sometimes still overexert themselves.

© Designed by Freepik

Local empowerment

Social, economic and political systems are decentralised. As far as possible, public policies are debated and adopted with the involvement of citizens, and non-governmental groups are actively engaged in political processes. As in society at large, there is a strong emphasis on experimentation in governance, with the lessons learned widely shared and discussed on social media, at the market or in the town hall. At the European scale, the EU persists but is relatively weak, although it is not exactly an unnecessary ‘empty shell’, as some complain. Member States normally join forces flexibly in ‘coalitions of the willing’ to tackle policy areas such as defence, taxation or social affairs. Cities, regions and non-governmental groups and networks have a strong voice in EU policy discussions.

Europe is inward looking. It contributes massively to climate change mitigation and reacts to disaster relief calls from the United Nations. But it does not see its role as including engaging in conflicts and local wars elsewhere in the world. In retrospect, most people regard the development and aid programmes of past decades as counterproductive. Asylum seekers — politically persecuted people — are welcome; war refugees are welcome to a certain extent; migrants are mostly unwelcome. Some people have a simple ecological interpretation: ‘Europe has reached carrying capacity’.

Economic activities and sectors are similarly fragmented and localised. Decentralised digital currencies (some of them successors to local and regional currencies) are used to boost local economies or reward unpaid work (e.g. care for the elderly). Businesses are often managed by stakeholders, including customers, employees and local communities. The energy sector is likewise highly decentralised. Private households and commercial units produce and store energy through a mix of renewable sources. Many homeowners and communities aim to be completely self-sufficient. Centralised energy production is largely reserved for industries. Nuclear power plants are close to being completely decommissioned.

Declining economic activity has alleviated some of the social and environmental pressures that previously demanded public spending. Finding ways to live and do business within nature’s limits is now part of society’s ‘common sense’. Ecosystems are prized for their inherent value rather than their capacity to generate profits. The widespread desire to reconnect with the natural world (together with other factors such as new technologies enabling remote working) has encouraged people to move out of cities to ecovillages and local sustainable communities in rural areas. Some have adopted a specific philosophical or religious orientation, sometimes in line with traditional forms of esotericism.

© Designed by Gabriel Jimenez on unsplash

Reconnecting with nature

Many agricultural regions that had previously been abandoned have been reinhabited. Natural resources are managed with the aim of maximising biodiversity and ecosystem health and resilience, rather than economic returns. Agriculture is generally smaller scale and much more diverse. Small farms, often run by cooperatives, provide high-quality nutritious food and recreational opportunities for families; some are an integral part of ecosystem rehabilitation schemes. Just as citizens wish to reconnect with nature, more engaged consumers want to reconnect with their food, understanding more about how it is sourced, processed and produced. Environmental and health problems associated with intensive agriculture and long food chains, now almost a spectre of the past, have led most consumers to favour organic and local food.

Meanwhile, nature has been invited back into towns and cities, with public authorities making land and resources available for engaged citizens to greatly expand blue and green urban areas. In many places, decommissioned infrastructures — such as former motorway junctions — have been dismantled. Their space has been given back to nature. ‘Gardening’ is a widely used catchphrase: let’s undo the harm done to nature and transform the spoilt environment into a garden.

In the middle of the century, lifestyles across Europe, in villages as in cities, have become more relaxed, more frugal, more cheerful than in previous years. Some of the older people would add that life is more sedate, even more complacent. Deceleration, once an academic concept, has become reality.

Document Actions

Share with others