Home to numerous different species and habitats

Europe’s seas cover more than 11 million km2 and range from shallow, semi-enclosed seas to vast expanses of the deep ocean. They host a wide and highly diverse range of coastal and marine ecosystems with a large variety of habitats and species (Box 1; EEA, 2015).

‘Biological diversity is the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.’

Source: UN, 1992, Convention on Biological Diversity

The Mediterranean Sea, for example, is one of the world’s hot spots for biodiversity. Its highly diverse ecosystems host up to around 18% of the world’s macroscopic marine biodiversity (Nike Bianchi and Morri, 2000), or potentially over 17,000 species (Coll et al., 2010). In comparison, the Bothnian Bay in the Baltic Sea hosts only approximately 300 species, making it vulnerable to anthropogenic change (HELCOM, 2018a).

No matter how species many a marine ecosystem hosts, they fill all available ecological niches. The species interact with and depend on each other through food web dynamics, competition for space or mutual synergies that provide shelter or foraging areas.

Together, these entities are the foundation of a marine ecosystem’s capacity to provide services and benefits for humanity (EEA, 2019a). These services are the final outputs of marine ecosystems, and are directly consumed, used or enjoyed by people (EEA, 2015). They include food, medicines, building materials, energy and opportunities for leisure. Less tangible outputs, such as limiting coastal erosion or mitigating climate change are also provided.

In short, humans and our societies depend on healthy seas with thriving marine life for our well-being and, ultimately, our very existence.

Seas are changing rapidly and marine life is under threat

The use of Europe's seas — both in the past and today — is taking its toll on the overall condition of marine ecosystems. This puts expectations for their future use at odds with the long‑term policy vision for clean, healthy and productive seas (EEA, 2019a).

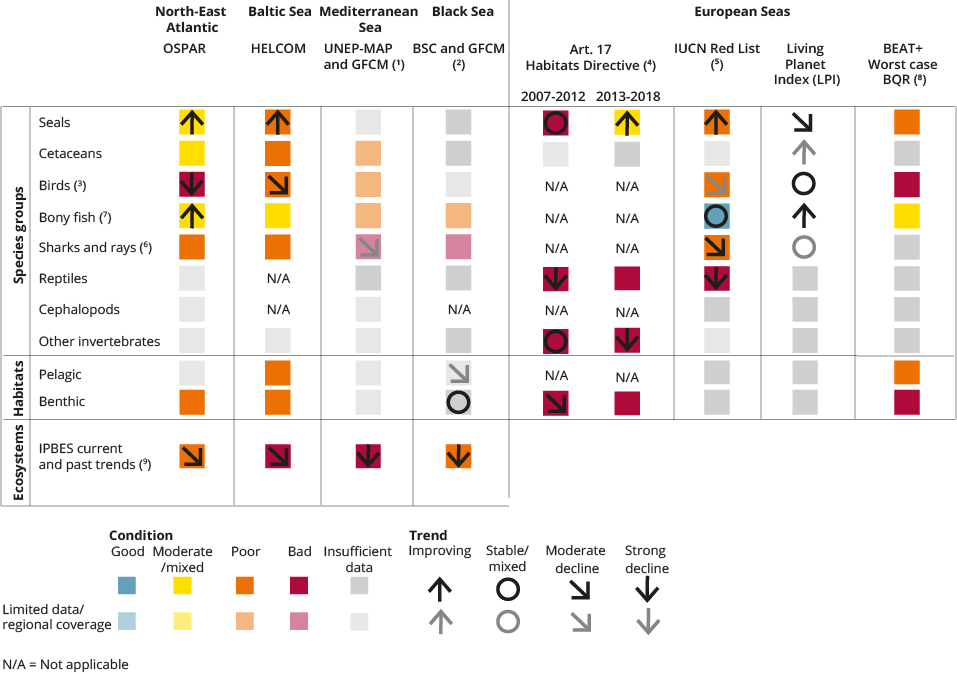

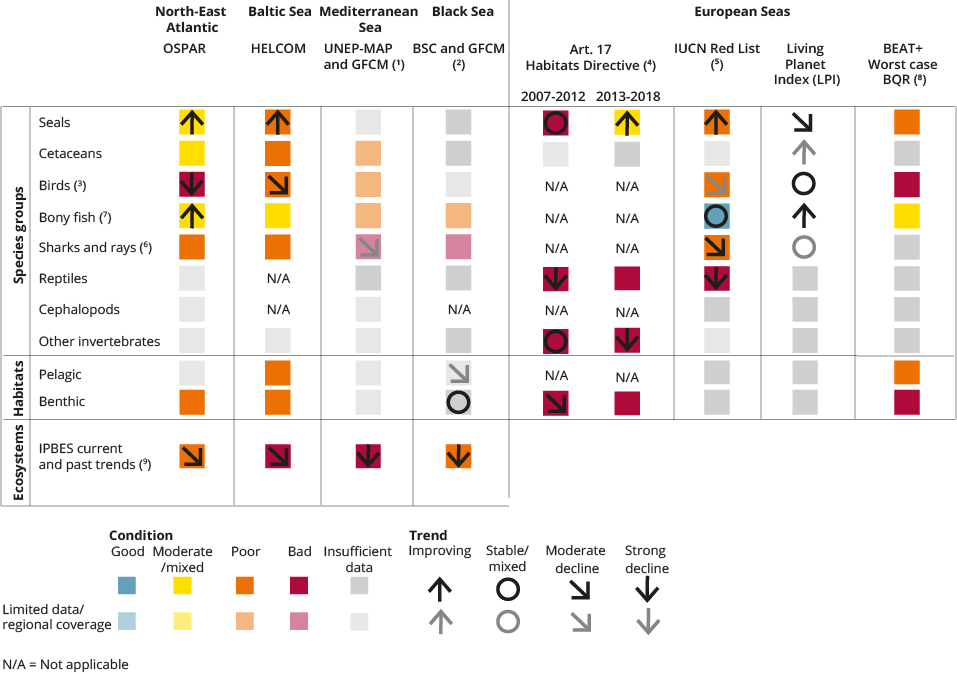

Signs of stress are visible at all scales — from changes in the composition of marine species and habitats to a shift in the seas' overall physical and chemical characteristics (EEA, 2018; EEA, 2019b; ETC/ICM, 2019a; ETC/ICM, 2019b). Looking closer at the overall condition of marine biodiversity in Europe, some disturbing conclusions emerge (Figure 1):

- Almost all marine species groups appear to be in bad condition throughout Europe’s seas, with mixed recovery trends.

- For many species and habitats, there is too little information to analyse their status or identify whether they are on track towards recovery.

- While some species are recovering, Europe’s marine ecosystems appear to be in decline.

Notes: For details on sources and methodology, please refer to (ETC/ICM, 2019a).

From the latest information reported under the Habitats Directive (Figure 1), it is clear that there has been little recovery since 2007. The only exception seems to be some, but not all, seal populations.

The condition of the populations of commercially exploited fish and shellfish species in Europe's seas (for which sufficient data exist) presented a contrasting picture for the period 2015‑2017 (EEA, 2019a).

In 2017, the condition of fish stocks in North‑East Atlantic Ocean and Baltic Sea populations started to improve. A total of 82.3% and 62.5% of these seas’ stocks, respectively, appear to be fished sustainably. However, the condition of some individual stocks, such as cod, have not started to improve in these regions (EEA, 2019a).

In contrast, the condition of assessed fish stocks in Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea populations remains critical. Only 6.1% and 14.3% of these stocks, respectively, were fished sustainably in 2016 (FAO, 2018; Jardim et al., 2018; UNEP‑MAP, 2018). However, Europe does not yet assess single stocks according to the three primary criteria identified in the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (EEA, 2019a) i.e. we have not yet implemented this part of our ambitions set out in 2008.

There are more than 180 species of sea birds in Europe. Average European sea bird population trends are either stable or declining. In the Norwegian Arctic Ocean, the Greater North Sea and the Celtic Sea, there has been an overall drop of 20% in sea bird populations over the last 25 years for more than a quarter of the species assessed (OSPAR, 2017a).

Marine mammals are all protected by EU legislation, though their status is often ‘unknown’. Some seal populations are healthy and are reaching carrying capacity[1] (e.g. harbour seals in the Kattegat, although they are decreasing in other areas) (OSPAR, 2017b; HELCOM, 2018b). Overall, in the 2014-2019 period, the status of seals had improved compared with 2007-2013 reporting under the Habitats Directive (EEA, 2020a). In the Mediterranean Sea, the number of monk seals appears to be stabilising, although this species is still at risk because of its small population size (Notarbartolo di Sciara and Kotomatas, 2016).

Recent studies of European populations of killer whales show the adverse effects of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) on their reproduction, with 50% of the global population under threat. In contrast, since 1994 populations of minke whale, harbour porpoise and white‑beaked dolphin appear to be stable (OSPAR, 2017b).

Seabed habitats are under significant pressure across Europe’s seas, with a high proportion of protected seabed habitats reported as being in 'unfavourable' and/or ‘unknown’ conservation status (EEA, 2020a).

Similarly, 86% of the assessed seabed in the Greater North Sea and the Celtic Sea shows evidence of physical disturbance by bottom‑touching fishing gear (OSPAR, 2017c). In the Baltic Sea, only 44% and 29%, respectively, of the soft‑bottom seabed habitat area in coastal waters and in the open sea were in 'good' status (HELCOM, 2018a).

These figures pale in comparison to the results of a recent study on the catastrophic climate-driven extinction of marine species in the eastern Mediterranean Sea over the last decade. Scientists have found that native species of molluscs (mussels, snails, octopuses, etc.) have collapsed by almost 90%, leaving behind a barren wasteland sensitive to incursions of non-indigenous species from the Suez Canal. Scientists ‘suggest that this novel ecosystem may well have crossed thresholds that make the restoration of historical baselines not achievable’ (Albano et al., 2021).

As such, biodiversity remains under threat in Europe's seas. These findings are further supported by 2018-2019 reporting under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive and the nature directives, as well as by scientific research (EEA, 2020a; EEA, 2020b).

Hope remains for the future of Europe’s marine life

While the situation remains serious, there are signs that marine species and habitats are recovering. This is because of significant, often decades‑long, efforts by individuals and governments to reduce impacts.

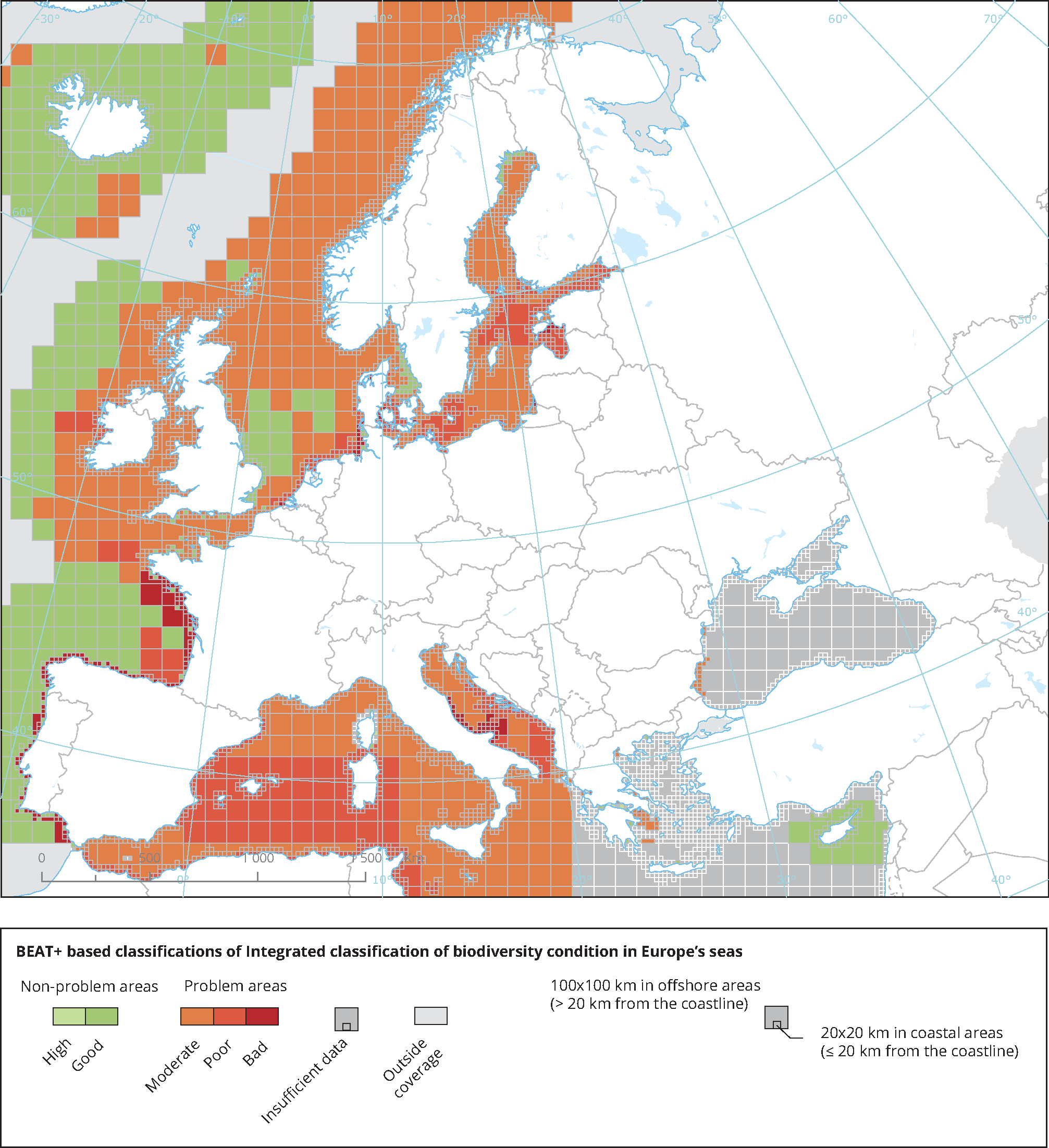

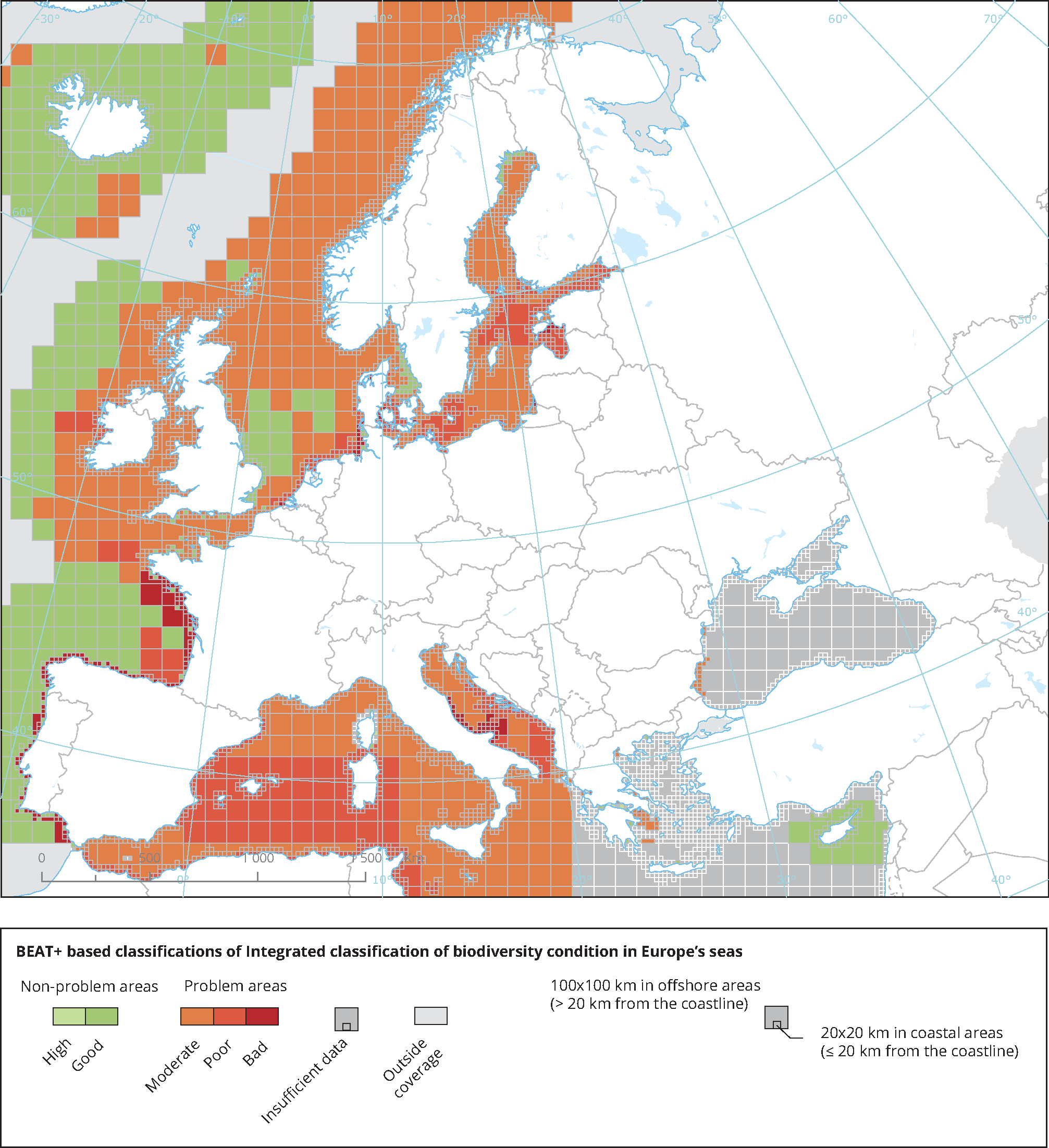

As such, the situation is not equally dire across Europe’s seas. Compiling all available information into an integrated classification of the condition of biodiversity shows that some, mainly offshore, areas in the North-East Atlantic Ocean are still in good condition. However, coastal areas and semi-enclosed seas still face significant challenges regarding the recovery of the entire ecosystem (Figure 2).

Notes: Based on BEAT+ classification of biodiversity in Europe’s seas’. For further details on classification methods, please refer to (EEA, 2019a) and (ETC/ICM, 2019a).

More information here.

Management of individual commercial species can be successful. For example, strong regulation to reduce fishing mortality brought the bluefin tuna back from the brink of collapse in 2005‑2007. It will possibly reach sustainable levels for fishing mortality and reproductive capacity in 2022 (EEA, 2019a).

There have also been positive results from the banning of certain substances. For example, the common dog whelk, a bottom‑living mollusc native to the Norwegian coast, is recovering in response to banning tributyltin (TBT; Schøyen et al., 2019).

Similarly, there are examples of the recovery of other individual species because of targeted management efforts such as the banning of PCBs and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). This has resulted in the recovery of the white‑tailed eagle in parts of the Baltic Sea after 35 years of efforts (HELCOM, 2018c).

Although these examples remain fragmented, they not only provide emerging lessons for recovery, but also a ray of hope. The EU still has a chance to restore marine ecosystem resilience piece by piece if it acts urgently and decisively to better balance human use of our seas with its impacts on marine ecosystems (EEA, 2019a).

Moving towards healthy European seas, thriving with life

With the vision outlined in the EU Green Deal and the supporting policy framework, EU Member States have not only recognised this urgency for action, but also decided to act upon it. This has resulted in the most ambitious policy framework for the recovery of European nature ever to be put in place by the EU.

Key among its ambitions is to reverse the loss of biodiversity by 2030 through a set of actions outlined in the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2030. These include, among others:

- strengthening the coherence of the network of protected areas;

- actively restoring ecosystems across land and sea;

- introducing measures to enable the necessary transformative change.

Achieving these ambitions by 2030 will require:

- building on the lessons learnt from existing management efforts that have delivered improvements for marine biodiversity;

- closing the implementation gap to ensure existing policy commitments are met on time; and

- closing the knowledge gap to ensure measures put in place are efficient and cost-effective.

Reversing the loss of biodiversity remains a generational challenge. Europe has the knowledge and capacity to successfully face this challenge. With the EU Green Deal policy framework, we are now showing the will to step up our efforts in making the changes so urgently needed.

Notes

[1] the number of animals, which a region can support without environmental degradation.

References

Albano P. et al., 2021, Native biodiversity collapse in the eastern Mediterranean, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Coll, M., et al., 2010, 'The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: estimates, patterns, and threats' Bograd, S. J. (ed.), PLoS ONE 5(8), p. e11842.

EEA, 2015, State of Europe’ seas, EEA report 2/2015.

EEA, 2018, Contaminants in Europe’s seas, EEA report, 25/2018.

EEA, 2019a, Marine Messages II, EEA report 17/2019.

EEA, 2019b, Nutrient enrichment and eutrophication in Europe’s seas, EEA report 14/2019.

EEA, 2020a, State of nature in the EU — Results from reporting under the nature directives 2013-2018, EEA Technical report 10/2020.

EEA, 2020b, WISE-MARINE – Marine Information System for Europe.

ETC/ICM, 2019a, Biodiversity in Europe’s seas, ETC/ICM report 3/2019.

ETC/ICM, 2019b, Multiple pressures and their combined effects in Europe's seas, ETC/ICM report 4/2019.

FAO, 2016, The state of Mediterranean and Black Sea fisheries 2016, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

HELCOM, 2018a, State of the Baltic Sea — second HELCOM holistic assessment 2011-2016, Baltic Sea Environment Proceedings No 155, Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission, Helsinki, Finland.

HELCOM, 2018b, HELCOM indicators — Population trends and abundance of seals, HELCOM core indicator report, Helsinki Commission, Helsinki, Finland.

HELCOM, 2018c, HELCOM indicators — White-tailed sea eagle productivity, HELCOM core indicator report, Helsinki Commission, Helsinki, Finland.

Jardim, E., et al., 2018, Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) monitoring the performance of the common fisheries policy (STECFAdhoc-18-01), Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Nike Bianchi, C. and Morri, C., 2000, 'Marine biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: situation, problems and prospects for future research', Marine Pollution Bulletin 40(5), pp. 367-376.

Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. and Kotomatas, S., 2016, 'Are Mediterranean monk seals, Monachus monachus, being left to save themselves from extinction?', Advances in Marine Biology 75, pp. 359-386.

OSPAR, 2017a, OSPAR intermediate assessment 2017, OSPAR Commission, London.

OSPAR, 2017b, 'Mixed signals for marine mammals', OSPAR Assessment Portal.

OSPAR, 2017c, 'Extent of physical damage to predominant and special habitats', OSPAR Assessment Portal.

Schøyen, M., et al., 2019, 'Levels and trends of tributyltin (TBT) and imposex in dogwhelk (Nucella lapillus) along the Norwegian coastline from 1991 to 2017', Marine Environmental Research 144, pp. 1-8 (DOI: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2018.11.011)

UN, 1992, Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nations Environment Programme.

UNEP-MAP, 2018, 'Mediterranean 2017 quality status report', United Nations Environment Programme.

Identifiers

Briefing no. 31/2020

Title: Europe’s marine biodiversity remains under pressure

HTML - TH-AM-20-031-EN-Q - ISBN 978-92-9480-353-5 - ISSN 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/490726

PDF - TH-AM-20-031-EN-N - ISBN 978-92-9480-352-8 - ISSN 2467-3196 - doi: 10.2800/37575

Document Actions

Share with others