Key findings

At the Sixth 'Environment for Europe' Ministerial Conference held in Belgrade in 2007, environment ministers made a new request for a further pan-European report, asking the EEA to consider producing a fifth assessment. At the same time a reform of the 'Environment for Europe' process was called for in order to improve its focus and make it more policy relevant. The reform plan was approved by the UNECE Committee on Environmental Policy in early 2009 and adopted by UNECE at its sixty-third session.

During the two years following the Belgrade Conference, reflections about producing a fifth assessment pointed to the need for a reform of the process. This was already contained in the report produced by EEA for the 2007 Belgrade Ministerial Conference on lessons learned to be used for future environmental assessment and reporting work in the region (4). It concluded that to improve the pan-European assessment it was necessary to:

- Establish systematic data exchange (every year as a minimum) with countries in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia (European Neighbourhood Policy countries, the Russian Federation and Central Asian countries).

- Strengthen the cooperation and partnerships between international organisationsin terms of working together to obtain good environmental information, sharing the information available and better coordinating their information demands towards countries.

- Continue activities of the UNECE Working Group on Environmental Monitoring and Assessment on a more regular basis.

- Run open consultations with the countries during the different stages of the report's preparation.

Given the major challenges faced at a pan-European level, two recent developments were taken into consideration for reforming the pan-European environmental assessment process:

i) The European Union (EU) initiative on a Shared Environmental Information System (SEIS) and

ii) The United Nations experience in the preparation of the Marine Assessment of Assessments, launched in 2005 by United Nations General Assembly (http://www.unga-regular-process.org).

Considering these developments an agreement was reached by the UNECE's Committee on Environmental Policy in 2009 to carry out an assessment of existing European environmental assessments, instead of developing a new fifth pan European environmental assessment. This exercise, named Europe's environment — An Assessment of Assessments, was carried out by EEA under the guidance of a steering group to assist the preparation of the report for the Astana Conference.

The agreement on developing the EE-AoA process was recognised as an important first step in reforming the future of European environmental assessments. The main purpose was 'to provide a critical review and analysis of existing environmental assessments that are of relevance to the region and the two selected topics for the Astana Conference, to identify gaps that need to be covered and priorities that should be addressed for conducting assessments to keep the pan-European environment under continuous review' (ECE/EX/2010/L.6, annex I, para. 1).

While a first major outcome of this was to produce a report for the Astana Ministerial Conference, the process was seen to be a longer-term activity, with the potential to continue after the Conference to cover other topics and provide the basis for developing a sustainable assessment process across all environmental topics, including inter alia the regular updating and sharing of relevant information.

Thus, the EE-AoA is not a new assessment of environmental issues but an analysis and assessment of the methods and underpinning information tied to the policy debate to support improved outcomes as reflected in the recent assessments available across the pan-European region. The two themes of the Astana conference, water and related ecosystems and green economy, served as the basis for production of the EE-AoA. Building on the 'Assessment of Assessments' (AoA) methodology, this assessment introduces a number of novelties which can be summarised as follows:

- Enhanced ownership through a participatory process. Individual countries through dedicated networks had a lead role in the EE-AoA process by providing the information input into the process and by being involved in the critical evaluation of the information. Besides countries, United Nations subsidiary bodies (UNECE, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)), EEA and other international organisations such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), actively contributed to the process making it a concerted effort at the pan-European level and at the regional level, the latter especially through the concrete contribution of the Regional Environmental Centres (RECs) in the preparation of the four sub-regional AoA reports under EEA coordination.

- A modular and flexible approach at various scales. The EE-AoA process may be applied at the national level and upwards, through an aggregation procedure that leads to 'regional assessments'. To further this objective, four regional AoA modules having the same thematic coverage were developed in parallel covering the countries in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia and the Russian Federation. Similarly, the AoA process has the potential to be disaggregated from the national level downwards to the sub-national/local level, an ability that may prove to be important for large countries such as the Russian Federation. Further, this modularity makes the approach flexible and replicable.

- A specific and challenging thematic focus. The EE-AoA dealt with two complex and totally different themes. The main challenge was to understand and capture their complexity at both national and regional levels through the use of common tools, necessarily kept as simple as possible to be effectively used by a wide range of contributors.

- Consistency ensured through guidelines and capacity-building. As countries and international organisations were invited to nominate their representatives to contribute to the assessment process, the production of guidelines to ensure a common understanding of the process and of the objectives to be tackled became imperative. Furthermore, training and assistance was provided by EEA in order to ensure consistency and coherence of the process and also to develop capacities for further assessments.

- Interactive information technology platform for production and dissemination of the results. The high number of stakeholders involved in the assessment process made it essential to rely on a common platform for both the uploading and sharing of information. The EE-AoA portal (http://aoa.ew.eea.europa.eu/) acts as a repository of the knowledge, and a processing/analytical instrument allowing the generation of summary overviews and statistics for the public at large.

- Developing and enriching the AoA methodology and toolbox. All the tools used to implement the EE-AoA process are available in the EE-AoA portal for further use including their development path and description. These tools can also be considered as outcomes and products of the process.

1 Setting the scene

1.1 Context, aims and objectives

1.1.1 Introduction

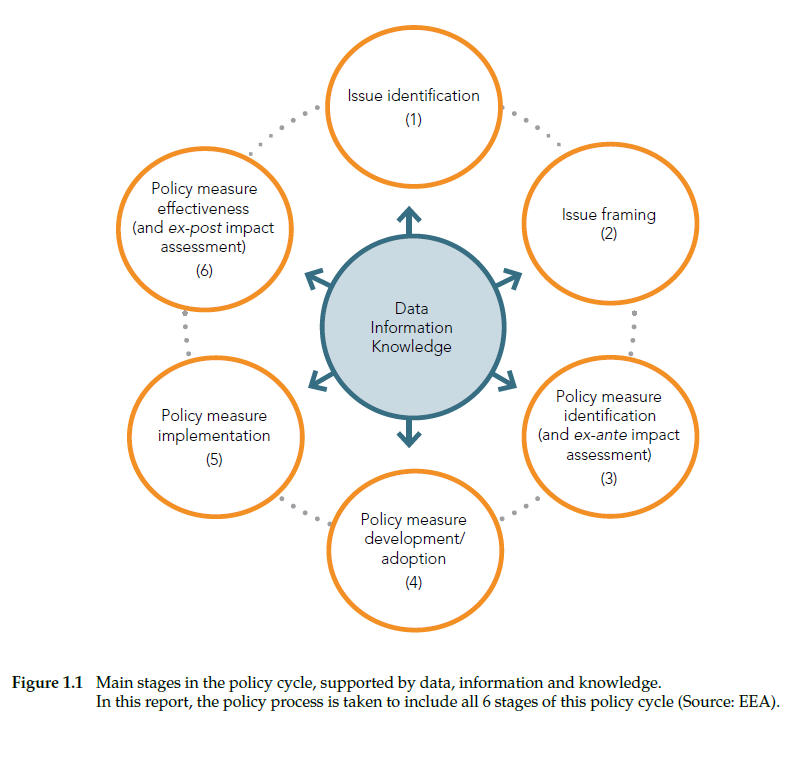

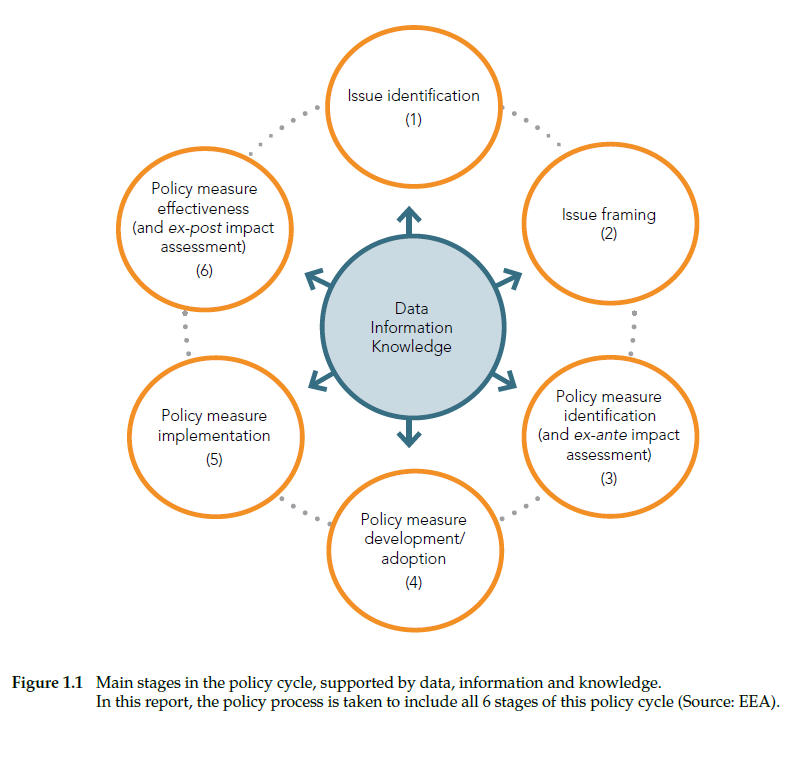

Environmental information is an essential component of the environmental policy process. This was recognised at the very first 'Environment for Europe' conference, held at Dobris Castle, near Prague, in June 1991. Since then, the types of information needed and for whom at different stages of the policy process have been further clarified. For example, progress has been made on specifying the information which is needed by different stakeholders for tracking progress and effectiveness of policies and distinguishing this from that needed for framing new issues. There are six main stages in the policy process (also referred to as the Policy Cycle), for which data and information are at the centre (Figure 1.1).

The European Environment Agency (EEA) has produced a series of four pan-European 'state of Europe's environment' reports in support of the UNECE 'Environment for Europe' process over the past 20 years (5). Over time, and in conjunction with a host of other reports (including the additional four five-yearly state and outlook reports produced by the EEA for its geographical area), this has resulted in a comprehensive overview of environmental challenges across the region.

To complement this, and in support of the 2011 Ministerial Conference, the European Environment Agency, supported by UNECE, has prepared a Europe's environment — An Assessment of Assessments (EE-AoA). This assessment of assessments focuses on the two themes of the Astana conference: water and related ecosystems, and green economy. Water issues are serious and worsening in many parts of Europe. Cross border regional solutions are essential. The green economy raises hope of a more equitable and sustainable development that respects all natural capital including water.

But what progress is being made? Is the right information available to be able to tell? And are the correct approaches to assess what is known being used to support the policy process? Given the volume of environmental reports, indicators and data available a huge amount seems to be known about these issues. But is all this informing the policy process effectively, and is the best being done with the resources available for assessment?

The aim of this AoA is to investigate these issues by assessing the assessments: cataloguing what exists, reviewing what is in them and analysing how they are put together. The overall objective is to improve the way in which the state of Europe's environment is kept under on-going review.

1.1.2 The growth in the number of European environmental assessments

Since 1995, the landscape of environmental information and assessments has become considerably more populated. This includes the increasing frequency of national-level 'state of environment' reports, indicator- and statistic-based environmental assessments and compendia, as well as thematic and sectoral assessments at country level, such as for transport, energy and agriculture.

Many more assessments are also now found at trans-country regional levels covering for example transboundary river basins, other ecological units such as mountains ranges (Carpathians for example), or lakes and inland seas including the Aral, Caspian, Baltic and Black Seas. Furthermore, at the European level, in addition to the pan European and EEA level assessments mentioned above, the multilateral environmental agreements also produce assessments, the most recent example being the second assessment of the UNECE transboundary rivers and international lakes convention.

In this process, some of the former gaps in data have been filled and the information, on which the assessments have been based, has become more timely. However, the data and information is still far from harmonised or equally accessible across the region. Most significantly, perhaps, the influence of the many environmental reports and assessments on the policy process and on improving the environment is unclear.

1.1.3 Efficiency and effectiveness of European environmental assessments

The increasing number of environmental assessments is on one level welcome, as the Aarhus Convention explicitly promotes the development of national 'state of environment' reports and accessibility to environmental information (see Box 1.1).

On another level, however, the growth in the number of environmental assessments in Europe over the past 15–20 years, and of environmental information in general, has led to an unclear overall picture, competing claims on resources with some overlaps and redundancies, while at the same time leaving some priority gaps still to be filled.

Before starting the AoA work, it was recognised that doing another pan-European assessment would not only create a competition for resources with EEA's mandated five-yearly assessment due in 2010, but also distract attention and resources away from the necessary long-term task of building an improved system to ensure the continuity and effectiveness of the assessment process.

The results of past reports, such as the 2007 Belgrade assessment, were still considered highly relevant and valid for supporting planning and prioritisation for the Astana conference due to the unfortunate long-term, persistent and often chronic nature of most of the environmental issues being assessed. Furthermore, the results of more up to-date reports, such as the EEA's 'State and outlook 2010' report (SOER 2010) and the second trans-boundary waters report, were already considered to cover much of the ground that a new 5th assessment should address, although restricted in geographical or thematic coverage.

It was becoming progressively clear that when commissioning, planning and launching new European-level environmental assessments, it was important to take broad stock of other related activities and past similar experiences and be clearer about the specific goals of any new assessment and its links to other assessments. This raises a number of issues including:

- the number of environmental assessments currently being commissionedand produced across Europe;

- the way they are being commissioned and produced; and

- their effectiveness in the way they are being put to use.

Overall, these concerns can be analysed under two headings:

1) Efficiency of production (of an assessment): Assessments put demands on many parties, especially countries to deliver data and review results but also on organisations. When multiple assessments are requested without coordination and appropriate means, this can create competing demands, lead to problems with the coherence and quality of results and strain overall resources.

2) Effectiveness of use/result (of the assessment): Assessments aim at strengthening the way that policy and action are underpinned by knowledge, but it is questionable whether this effectiveness increases in step with the number of assessments produced.

Box 1.1

The Aarhus Convention

The 1998 UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters is a new kind of environmental agreement that:

- links environmental rights and human rights;

- acknowledges that we owe an obligation to future generations;

- establishes that sustainable development can be achieved only through the involvement of all stakeholders;

- links government accountability and environmental protection;

- focuses on interactions between the public and public authorities in a democratic context.

The subject of the Convention goes to the heart of the relationship between people and governments. It is not only an environmental agreement, it is also a Convention about government accountability, transparency and responsiveness.

The Aarhus Convention grants the public rights and imposes on parties and public authorities obligations regarding access to information, public participation and access to justice. The Aarhus Convention is also forging a new process for public participation in the negotiation and implementation of international agreements.

Source: From UNECE website: http://www.unece.org/env/pp .

1.1.4 The process towards an EE-AoA

At the Sixth 'Environment for Europe' conference held in Belgrade in 2007, ministers initiated a reform of the 'Environment for Europe' process in order to improve its focus and make it more policy relevant. A reform plan was approved by the UNECE Committee on Environmental Policy (UNECE/CEP) in January 2009 and adopted by the 63rd session of the UNECE in March/April 2009.

The reform plan envisages that the decision on themes to be prioritised at ministerial conferences should take into account 'preliminary findings of available assessments and statistical reports on environment' and that the 'official substantive documentation' produced for the Ministerial Conferences should be limited to 'the pan-European assessment and theme-specific reports' as key inputs to and outputs of the conferences.

Following agreement on the reform plan, the UNECE Committee on Environmental Policy asked the EEA to host a high-level consultation with countries and organisations involved and with regional and international partners to consider options for the next assessment. Building on the recommendations in the EEA's 4th assessment report on lessons learnt, the aim was to help bring more clarity to future pan-European environment assessment activities and in particular to help better specify what to produce for the Astana Ministerial conference in 2011.

The high-level consultation took place on 3 July 2009 at the EEA and addressed the following main five aspects:

- the need and use of future pan-European environment assessments and especially as an input to and output of the 2011 Astana Ministerial conference;

- the latest experiences and current trends in producing and using assessment results to support knowledge-based environmental policy development, implementation and decision-making across the region;

- ways to improve the effectiveness of different environmental assessment activities at different levels across Europe through better linking, sharing and cooperation;

- ways of engagement with stakeholders and concrete ways for streamlining the production, use and communication of related assessment activities with the long term aim of developing a streamlined and sustainable assessment process serving multiple purposes including organising the necessary relationships between all the different actors, organisations and other components involved;

- key knowledge gaps for priority action to improve the information base on which assessments are founded and gradually extending the Shared Environmental Information System (SEIS) on the basis of its principles and component parts.

These questions were all placed in both the specific context of the 'Environment for Europe' process, including preparations for the Astana conference, and also beyond so as to start building a long-term, sustainable and regular assessment-reporting process on the European environment. Agreement was sought on the future place and role of an improved pan-European environment monitoring and assessment process to which all countries and organisations of the region could be partners and contributors.

Given the major challenges faced at a pan-European level, two developments were underlined to be taken into consideration for reforming the pan-European environmental assessment process:

i) the EU initiative on the Shared Environmental Information System (SEIS) http://www.eea.europa.eu/about-us/what/shared-environmental-information-system(http://www.eea.europa.eu/about-us/what/shared-environmental-information-system ); and

ii) the UN experience in the preparation of the Marine Assessment of Assessments, process launched in 2005 by the UN General Assembly resolution 60/30(http://www.unga-regular-process.org ).

After detailed discussions, agreement was reached by the UNCEE's Committee on Environmental Policy in its meeting in October 2009 to carry out an assessment of existing European environmental assessments, instead of developing a new 5th pan European environmental assessment. This exercise, which was named Europe's environment — An Assessment of Assessments (EE-AoA), was requested by the UNECE Committee on Environmental Policy to be carried out by the EEA under the guidance of a steering group to assist the preparation of the report for the Astana Conference. This agreement was endorsed by the UNECE Executive Committee in February 2010, enabling the process to begin (6).

The agreement specified that the overall goal is 'to assess the regional needs, priorities and sustainable long-term mechanisms to keep the pan-European environment under continuous review' and to make concrete proposals to this effect including 'recommendations on how to develop a shared environmental information system in the region'.

The first such Assessment of Assessments, in the field of the global marine environment (Box 1.2), was a pioneer in determining the foundations for the development of a regular process for global reporting and assessment. While a first major outcome of the EE-AoA was to produce a report for the Astana Ministerial Conference focused on the two conference themes (water and related ecosystems and the green economy), the process was seen to be a longer-term activity with the potential to continue after the conference to provide the basis for developing a sustainable assessment process across all environmental topics, including inter alia the regular updating and sharing of relevant information.

Nevertheless, compared with the single thematic focus of the Marine AoA, the two Astana ministerial conference priorities cannot be easily dealt with as separate topics for an Assessment of Assessments since they are both interconnected and of different natures: water and related ecosystems form part of the main 'assets' of the green economy, while the Green Economy is a set of principles, aims and actions across the socio-economic domain that not only depends on these assets to deliver increased human welfare, but also at the same time is expected to positively impact on them to build resilience for the future. Thus it was recognised from the start of the EE-AoA exercise that, while it may be possible to clearly refer to an Assessment of Assessments for water, such a reference is not similarly clear for the Green Economy due to its wide scope and uncertainties conceptually.

Box 1.2

The UN Marine Assessment of Assessments — towards a regular process

The UN Marine Assessment of Assessments was a major achievement involving country contributions, international organisations, experts and non-governmental organisation participation. The idea was to appraise what had been achieved to date with the many regional and global marine assessments regionally and globally and to make recommendations to streamline and improve such activities in the future to improve quality and effectiveness.

Building the knowledge network was the most valuable part of the Marine Assessment of Assessment. The assessment demonstrated the importance of scientific credibility, political relevance and legitimacy for effective assessments. These were underpinned by good data flows and indicators. The success of these factors relies on the set-up and management of the process.

Though limited in scope to the state of the marine environment, the Marine AoA served as the basic inspiration and starting point for the EE-AoA.

1.2 What is an AoA?

An AoA is essentially about reforming how environmental reporting and assessment is carried out to support the policy process. This is entirely complementary to the issue that SEIS has been designed to tackle with respect to environmental data and information. The EE-AoA, focused on assessments, is therefore effectively kicking off a new field of SEIS activities.

This section describes the criteria and analytical frameworks on which the EE-AoA was built and against which the assessments were evaluated. This more conceptual and idealised description is complemented in Section 1.3 by an explanation of how the EE-AoA was implemented in practice, including comparisons to the Marine AoA. Both sections aim to provide the conceptual and methodological underpinning to understand the present exercise, as well as offer explanations and reflections on the approaches and methods used so that they may be taken up elsewhere as appropriate.

1.2.1 What is an assessment?

Strictly speaking, an assessment is a formal process of appraisal against various standards or criteria. Environmental assessments usually refer to works that either bring to light the consequences of scientific findings on environmental processes or track changes and progress, often against environmental standards or targets. In the present context seeking improved ways of governing environmental knowledge to support the policy process, the aim of environmental assessments is to support the framing and implementation of environmental policy and more generally to support the transfer of knowledge and translation and communication across the so-called science-policy interface.

1.2.2 Criteria and frameworks for assessing the assessments

As mentioned in Section 1.1, the two main challenges underlying the EE-AoA are those of efficiency of assessment production and effectiveness of the assessment result. Two specific frameworks have been used to analyse these qualities.

First, the Saliency-Credibility-Legitimacy framework (7) provides a reference for analysing the effectiveness of assessments. Thus, for example, by analysing how and for what reasons assessments are commissioned in the first place, saliency can be assessed. By analysing the basis and source of information underlying an assessment, a measure of the assessment's credibility is formed. Furthermore, analysing the stakeholder engagement in an assessment exercise helps provide a measure of legitimacy which affects the uptake of the results, leading in turn to real improvements in the environment. These aspects are not mutually exclusive and an analysis using this framework can reveal important insights into the implicit or intentional trade-offs being made between them.

SEIS provides a second framework of components which together address efficiency and effectiveness:

i) common content: a common set of indicators helps link and streamline assessments (efficiency) and make them policy relevant (effectiveness);

ii) organisational matters: having agreed institutional arrangements increases access to and transparency of information (efficiency and effectiveness); and

iii) on infrastructure and tools: availability of reporting tools helps reduce the burden on countries to make information available (efficiency) and helps improves quality (effectiveness).

In addition, the MDIAK and DPSIR conceptual frameworks developed by EEA (see Boxes 1.3 and 1.4) are useful tools to clarify in greater detail the type of information that underpins the assessments analysed by these two frameworks. Thus, the MDIAK reporting chain supports an analysis of the basis of the information used in the assessment and whether this can be traced — an aspect that underpins credibility. The DPSIR analytical framework, meanwhile, helps clarify the scope of the assessment and the degree to which assessments are integrated across the cause-effect chain, or narrowly-based focusing on, for example, simple descriptions of the state of the environment.

Box 1.3

The MDIAK reporting chain

To help specify and distinguish between the different types of information needed in particular for countries to report on to support the policy process, the EEA uses the MDIAK framework specifying, in reverse order:

K What do we need to Know?

A What Assessments are needed?

I What Indicators are needed?

D What Data is needed at European level?

M What Monitoring is needed to deliver the required data?

Box 1.4

The DPSIR analytical framework

To structure thinking about the interplay between the environment and socioeconomic activities, the EEA uses the driving force, pressure, state, impact, and response (DPSIR) framework. This is used to help design assessments, identify indicators, and communicate results and can support improved environmental monitoring and information collection.

1.2.3 Applying the frameworks

There are two complementary dimensions of assessment that can be addressed by an AoA. The first concerns the methodological approaches and information underpinning the assessments. This gives rise to the following kinds of questions:

What types of assessments exist and what is the extent and type of underpinning information? And how were the assessments carried out, that is how do we come to know what we know?

The second dimension concerns the environmental issues themselves, which raises the following types of questions:

What do the assessments tell us about the issues at stake? And how are the issues understood across Europe, including the persistent and emerging challenges related to them and the steps being taken to tackle them?

The Marine AoA focused on the first dimension. Taking stock of the methodologies and data underpinning existing assessments enabled the Marine AoA to provide reflections and insights about how to develop a regular process for keeping the world's marine areas under on-going review. Producing a global marine assessment is seen to be a fruit of that new process.

This is also the case for the EE-AoA where priority has been given to an appraisal of the environmental assessment enterprise across Europe as a prerequisite to the development of a sustainable process in the future. Thus, the EE-AoA is not a new assessment of environmental issues but an analysis and assessment of existing methods and underpinning information.

1.3 The EE-AoA in practice

This section explains how the EE-AoA was implemented in practice. It overviews a number of key elements involved, approaches taken and assumptions made. This includes an overview comparison with the Marine AoA and lessons learnt from EE‑AoA process.

1.3.1 Key elements of the EE-AoA

The key elements of the EE-AoA are underlined below emphasising, inter alia, the novelties of the approach compared with the Marine AoA.

Links to SEIS

Since its launch, the EE-AoA process established a close link with the ongoing development of a SEIS in the pan-European region, seeking coherence with the main SEIS components and adherence to its guiding principles. The conceptual framework of the EE-AoA process is built around:

i) governance: as it is concerned with institutional arrangements and networking, scope and objectives, interaction and communication;

ii) infrastructure and services: as it deals with the support available for data management, sharing and exchange, and any INSPIRE/GMES/Reportnet compatible developments; and

iii) content: as it concerns information and data, indicators and assessment tools, priority concerns, needs and/or emerging issues, as well as information and/or knowledge gaps.

Distributed participation and ownership

Individual countries had a lead role in the EE-AoA process by providing the information input into the process and by being involved in the critical evaluation of the information. Countries were asked to coordinate at the national level the selection of relevant assessments and their uploading in the virtual library through existing network representatives. The EE-AoA process relied heavily on these existing governance structures to legitimise the process and without which the comprehensive participation of the stakeholders of the European UNECE countries/territories would not have been possible (see Box 1.5).

UN agencies (UNECE, UNEP, UNDP), the EEA and other international organisations such as OECD, actively contributed to the process thereby making it a concerted effort at the pan-European level. At the regional level, the Regional Environmental Centers (RECs) delivered concrete contributions as writers of the regional modules.

Multiple scales

One of the key features and novelties of the EE-AoA is its multi-scalar approach. With little or no adjustment, the rationale behind the EE-AoA process can be applied at the national level and upwards, through an aggregation procedure that leads to 'regional assessments'. By implementing the AoA methodology at various geographical scales, four sub-regional AoA components were developed for Central Asia, the Caucasus, Eastern Europe and the Russian Federation, each providing significant regional input to the main assessment. Similarly, the AoA process has the potential to be disaggregated, from the national level downwards to the sub-national/local level, an ability that may prove to be important for large countries such as the Russian Federation.

Box 1.5

EE-AoA: Experience from Finland

From a country perspective, the first major task in the EE-AoA process was to identify a set of assessments and enter some of the information included in these assessments in two platforms: the virtual library and the AoA review template. Both platforms were made available online by the EEA. At the request of Finland, the EEA arranged for such platforms to migrate into a national sub-system, identical to the main one but dedicated to the assessment process at the country level.

Relevant assessments related to water resources and the green economy are produced by a number of experts in a number of organisations, and the existence of a national sub-system allowed Finland to better coordinate the process of identification of relevant assessments, their screening and the inclusion of relevant information on to the two platforms. The process could thus be considered as work in progress at the national level up to the time the final deliverables were completed by all actors concerned. Once the process was finalised the information was transferred into the EEA system.

Separate national platforms framing the process at the national level have several advantages:

i) national coordinators keep better control of the process in terms of expert contribution and selection of relevant assessments, since internal evaluation and adjustments can continue until the best possible selection of assessments is obtained;

ii) countries monitor the production of deliverables and decide on amendments and adjustments of draft products as often as needed, and in a flexible way, i.e. from when experts first become involved up to when it is decided that the information is 'good enough' to be made publicly available on the main EEA platform;

iii) the EEA is released from the responsibility of coordinating a very large number of countries, leaving the Agency with a supervisory role, through the quality check of the virtual library and the review template, and a 'depository' role for the knowledge produced by individual countries.

From the IT point of view, the creation of sub-systems identical and fully compatible with the main system ensures inter-operability and smooth transfer of the information from the national level to the EEA.

Diverse content

The EE-AoA dealt with two complex and totally different themes. The main challenge was to understand and capture their complexity at both national and regional levels through the use of common tools, necessarily kept as simple as possible to be effectively used by a wide range of contributors. The review template was designed as the common instrument for the extraction of information related to both water and the green economy; theme-specific questions were not included and, instead, the selection of types of analysis addressed within each assessment under review, by theme/area/ topic, was preferred.

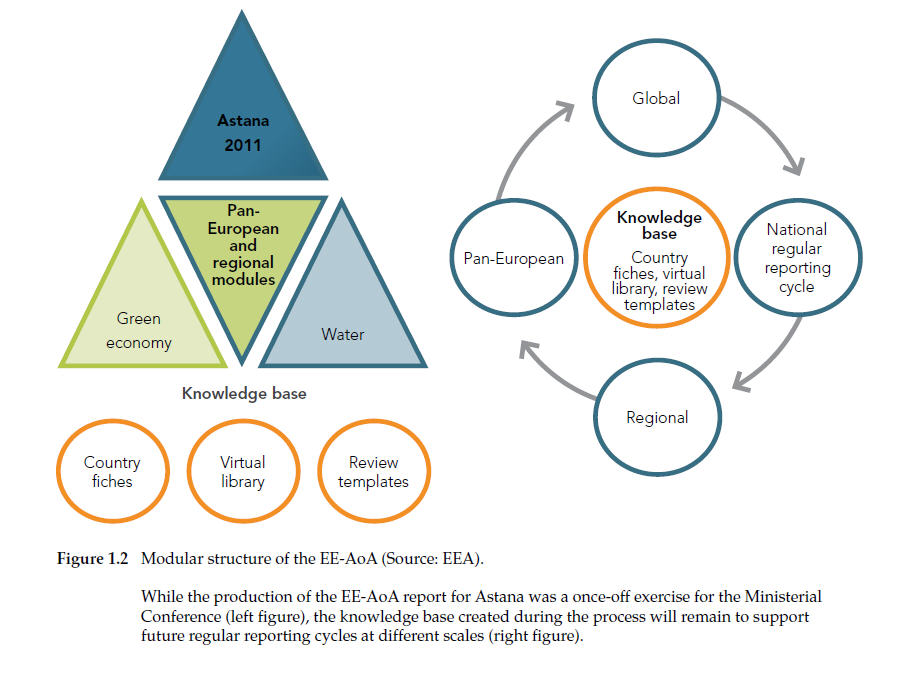

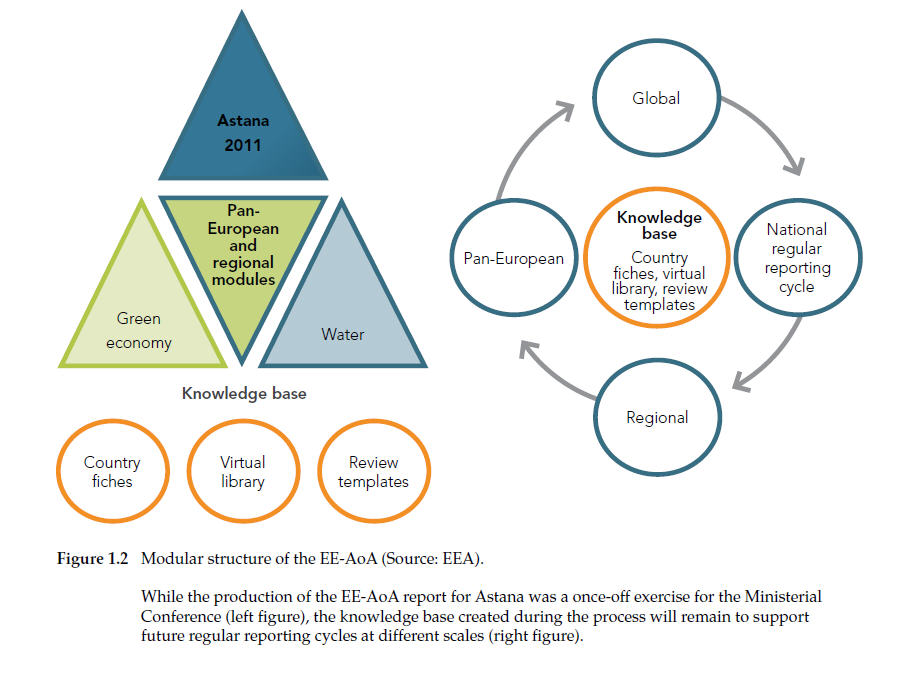

Modular structure

The EE-AoA is based on a modular approach, where different parts are developed within an overall framework setting common procedures, standards and tools. This modular approach was essential to adapt to the political agenda of the Astana Conference and to the diverse geographical sub-regions which had to be covered (see Figure 1.2 for details).

Capacity building

As a result of the country nomination process, a very heterogeneous and wide group of people became directly involved in the assessment process. Consequently, the production of guidelines to ensure a common understanding of the process and of the objectives to be tackled became an imperative. Training sessions were also carried out for those expected to make the largest contribution to the process.

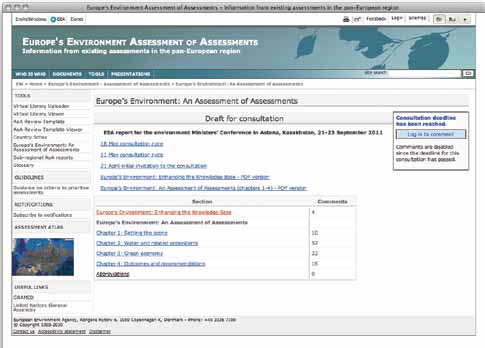

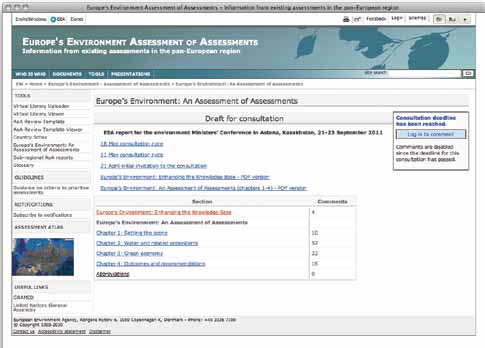

Common IT infrastructure

The high number of stakeholders involved in the assessment process made it essential to rely on a common platform for both the uploading and sharing of information. The EE-AoA portal was established to act as a repository of the knowledge, with an information window for both the contributors and for the general public, plus a processing/analytical instrument for the generation of summary overviews and statistics. Much of the information hosted on the portal is designed to be kept updated, so as to play a continuous supporting role in a regular reporting process. Figure 1.3 shows the sitemap of the portal.

Tools for implementation

An overview of the tools used to implement the EE-AoA process is found in Table 1.1 including their development path and description. These tools can also be considered as outcomes and products of the process for use in ongoing work. All are characterised by innovative features compared with the Marine AoA (see also Annex 1.1).

Table 1.1 EE-AoA: tools for implementation

Glossary

Development path

Compiled starting from the definitions agreed upon within the UN-led process of the Marine AoA, the EE-AoA glossary has been enriched with terms and concepts related to UN and EU processes, institutions and organisations.

Description

The list of acronyms/concepts is a dynamic tool meant to expand further as needs arise. It includes around 130 definitions (31 May 2011).

Criteria to prioritise assessments

Development path

These were built in particular on the selection protocol developed within the SOER 2010 AoA pilot module run by the EEA.

Description

A distinction is made between general and specific criteria. The general criteria recall the Marine AoA definition of 'assessment'. The specific criteria guide selection towards: the most recent assessment reports, possibly published within the last 5 years; the last published report in case of a regularly published series; assessment reports covering topics poorly addressed by other assessments in order to tackle the most comprehensive coverage of the topics under the two main themes; assessment reports covering emerging issues within the topics/ themes; assessment reports covering geographical areas that are poorly covered by the other assessments in order to tackle the most possible comprehensive geographical coverage at national, regional and transboundary levels.

Virtual library

Development path

Originally developed within the framework of the EE-AoA assessment process.

Description

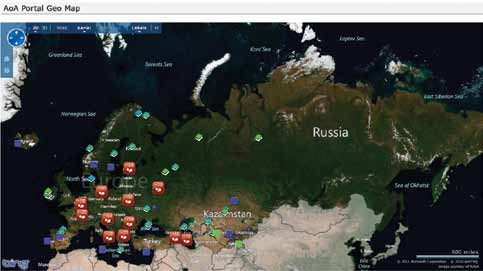

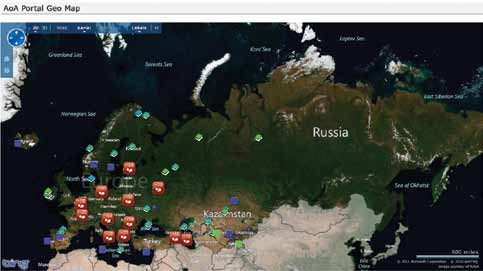

An online web-based library (hence, the reference to 'virtual') where registered contributors upload assessments considered relevant to the AoA process (see http://aoa.ew.eea.europa.eu). Registering in the library through the virtual library uploader requires little assessment-related information and the provision of the hyperlink to the report, if available on the web. The specification of the geographical location of the institutions conducting the assessments allows the generation of an assessment atlas (Figure 1.4). By mid-2011 the virtual library included over 900 assessments, evenly covering both green economy and water themes and with more than 70 per cent addressing national or local levels.

Country fiches

Development path

Originally developed within the framework of the EE-AoA assessment process.

Description

Country fiches (see: http://aoa.ew.eea.europa.eu) are summaries of the main sectoral reports, environmental statistics and indicator sets, as well as relevant performance reviews and major institutional players involved in environmental reporting. Developed to obtain an overview and to encourage the uploading of relevant assessments into the virtual library, they were submitted to country contact points and NFPs to correct and improve and then to highlight the five most important products. This was to help develop a balanced sample for the exercise, ensuring that a minimum set of information per country was uploaded into the EE-AoA portal and contributed to the AoA process. Country fiches are intended as dynamic overviews foreseen to be kept regularly updated and going beyond the AoA process, since they may represent models for the development of dynamic country profiles that may be supportive of future assessment exercises.

Review template

Development path

Building on the template used for the review of individual assessments within the Marine AoA, on the lessons learnt while developing the 'general template' within the SOER 2010 AoA exercise, and on the feedback and comments received during and after the AoA training workshop.

Description

The review template (see http://aoa.ew.eea.europa.eu ) is structured into eleven main parts and around the three main components of governance, infrastructure and services, and content. The review template is required to be filled only on the basis of the information explicitly stated and contained in the assessment reports under review. This means that 'background' information that may be known by the person filling out the templates, but that cannot be found in the assessment report, could not be included. This approach was taken due to the importance of transparency for effective assessments concerning the process, methods and about the underpinning data and information used. If these are not made explicit in the assessment then they are not open to scrutiny so cannot be taken into account in the AoA. Each review template uploaded by contributors underwent a quality control that ensured minimum quality standards for all 'approved' templates.

1.3.2 Lessons learnt from EE-AoA process

Some important lessons learnt during the implementation of the EE-AoA are recorded here. These findings may provide the basis for a reflection on future assessment needs, with a view to the way forward towards a regular assessment process.

Considerations relevant to the initiators of the process:

- the conceptual part of the assessment of assessments process needs to provide clear instructions to participating countries and organisations on the type of literature, reports and documents to be included in the process. The broad definition of 'assessment' used by the Marine AoA and adopted within the EE-AoA should be tailored to needs, especially with regard to the environmental policy priorities guiding the assessment process. For example, the selection of literature within the EE-AoA was perceived by some to be insufficiently focused on the two priority themes and analysis, and not always coherent across countries. The distinction between descriptive reports and assessments proved to be difficult to define;

- the review template needs to be developed further in terms of the clarity of the queries and of its ability to extract content-related information from the assessment.

Considerations relevant to countries:

- a better standardisation of the selection of literature by countries would increase the reliability of the process, ensuring more balanced contributions. Notwithstanding the outlining of common prioritisation criteria, each country was given the freedom to decide on the literature to be screened, leading to an unsystematic coverage of themes and topics across countries and regions.

On the other hand, the process revealed some important features and approaches that are worthy of consideration in maintaining or strengthening in a future exercise:

- inclusiveness of the process, engaging all players not only in the process itself but also in the conceptualising phase and in the shaping of the methodological approach;

- flexibility of the modular approach, allowing for aggregation and disaggregation of assessment processes at different scales as well as adaptation to different themes;

- transparency of the process, with high visibility achieved along all steps through continuous interaction, by virtual means (portal, internet-based conferences, etc.) and physical consultation (meetings) with major players;

- continuous process, initially intended to deliver to one major event (the Astana Conference) but laying down the foundations (conceptual framework, methodologies, main players, capacities, IT infrastructure and implementation tools) to serve multiple needs in an ongoing process and future events;

- building on existing networks and institutions/bodies, thus strengthening existing governance structures and, at the same time, facilitating future exercises since the main institutions and players have been already identified;

- enhancing the capacities of relevant stakeholders in contributing to the process in an objective and disciplined manner, thus adding to the sustainability of the process by empowering major players to actively participate to the process. Capacity building was specifically addressed to the Regional Environmental Centres (responsible for the sub-regional components), to all main players through the dissemination of the guidelines, and to all those uploading review templates into the portal, through the approval procedure of the templates (quality control);

- being closely linked to the establishment of SEIS a win-win situation is set up since SEIS will contribute in any future exercise to content development, networking and analysis development through a more efficient use of the information, more readily available and comparable information, and a virtual environment for sharing and processing.

Notes

4. 'Pan European Assessment Reports on the State of the Environment and associate activities lessons learned in working with countries in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia on the preparation of the Belgrade Report' (ECE/CEP/AC.10/2008/3).

5. 'Environment for Europe' process, see: http://www.unece.org/env/efe/welcome.html.

6. Establishment of the Steering Group on Environmental Assessments and its Terms of Reference. ECE/EX/2010/L.6. 18 December 2009. UNECE Executive Committee Thirty-fourth meeting, Geneva, 26 February 2010.

7. Cash, D., Clark, W., Alcock, F., Dickson, N., Eckley, N., and Jäger, J., 2002. 'Salience, Credibility, Legitimacy and Boundaries: Linking Research, Assessment and Decision Making'. John F. Kennedy School of Government Faculty Research Working Paper RWP02-046. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Document Actions

Share with others