Introduction

The Spanish coastline has a length of approximately 10.000 kilometres, there being a clear difference between two areas: the Atlantic maritime region and the Mediterranean maritime region. In turn, the Atlantic region can be divided into four sectors: the Cantabrian Sea and the Bay of Biscay, Galicia, the Gulf of Cadiz and the Canary Islands.

El Cachucho, Spain’s first Maritime Protected Area in Ospar Convention, is located in the Cantabrian Sea, in the waters of the Exclusive Economic Zone, at a distance of 60 kilometres from the Asturian coast, roughly at the centre of the northern coast whose length, from the Estaca de Bares cape to the French border, amounts to 1,085 kilometres.

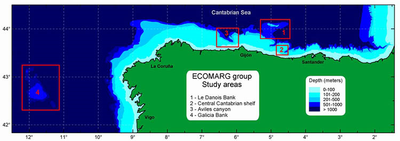

Location of El Cachucho (1) in the Cantabrian Sea, close to the Asturian coast.

Source: IEO. ECOMARG (Study of the continental margin ecosystems)

Due to the proximity of the equally named mountain range, with summits exceeding 2,500 metres in height (Picos de Europa), the Cantabrian coast is cliffed and has few inlets, save for the mouths of the rivers: over 94% of its length can be classified as rocky coast. The sea dynamics to which it is subjected -both concerning the swell and the tides and currents- is far more active than in the other seas bathing the Iberian Peninsula. In the Cantabrian Sea, waves more than 25-metre high have been measured and seeing 15-metre waves is not infrequent during the winter storms (gales).

This particular sea’s currents are sources of life, creating one of the most productive zones in the Iberian Peninsula, the so-called Galician outcropping, where plankton has a massive presence which makes up the foundation of the wealth of the Galician rias. It has been estimated that the Cantabrian Sea waters have a primary production (expressed in carbon) that may reach 200 gC/m2/year. The existence of a tidal oscillation exceeding four metres throughout the coastline -and even five metres in some places- is yet another feature setting these coasts apart from the rest of the Spanish seaboard.

Tides, currents and swells owe their existence to the peculiar location and the geographical arrangement of this area within the Northern Atlantic, which took place in the lower Tertiary. The geological origin is also at the root of the uniquely clear and elevated coastal plains (“rasas costeras” in spanish) found in Asturias and Cantabria, abrasion platforms whose origin dates back to the interglacial periods and which nowadays are emerged, shaping narrow plains whose surface forms a contrast with the mountainous landscape typical of these regions.

THE CANTABRIAN SEA SUBMARINE CANYONS REACH DEPTHS GREATER THAN 4,000 METRES

The Cantabrian coast’s eastern sector has a narrow continental shelf (hardly 10-kilometer wide on average), which gets broader in the area between the LLanes Canyon and the Avilés Canyon, and diminishes again beyond the latter geographical feature. The Cantabrian Sea’s continental margin includes a range of physiographical and geomorphological characteristics accounting for the high biodiversity rates found in the area.

A characteristic feature of the bottom of the Cantabrian Sea is the existence of several submarine canyons, such as the Santander, Torrelavega, Llanes, Lastres and Avilés ones (4,700 metres). The Galician Bank, located at the aforementioned sea’s boundaries, also deserves special mention. Submarine canyons are deep, rugged-slope valleys that originate in the continental shoulder and that can reach great depth. Some submarine canyons seem to be offshore extensions of river valleys, but in numerous cases, the research carried out also seems to point to their being excavated by “turbidity currents”, ocean currents carrying suspended sediment.

One of these submarine canyons is located at El Cachucho, Spain’s first Maritime Protected Area, a submarine mountain rising from the deep (4,000 metres) up to an area 500 metres away from the surface, that could be graphically described as some sort of “Underwater Picos de Europa”. El Cachucho, along with the rest of the Cantabrian Sea’s submarine canyons, make up a set of special relevance whose scientific value is quite exceptional within the Northern Atlantic and which is, therefore, included in the scope of protection provided by the OSPAR Convention.

The scientific discovery of El Cachucho (Banco Le Danois)

Spanish oceanography can boast of having among the number of its illustrious researchers two outstanding names who must take the credit for having founded it anew on the Nineteenth century’s scientific bases. These two men are Augusto González Linares (1845-1904), who participated in the establishment of the first Spanish marine biology centre (the Experimental Zoology and Botany Maritime Station, 1886) with headquarters in Santander, the region in which this scientist, linked to the renewing school of though of Krausism, was born and died.

The other distinguished scientist is Odón de Buen y del Cos (1863-1945) -also educated according to the spirit of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza- who takes the credit for being the founder of the Spanish Oceanographic Institute (IEO) in 1914. But it would be their French contemporary, member though he was of a later generation, the researcher Edouard Le Danois (1887-1958), who made the existence known of El Cachucho, which, as a result, is known in the scientific world as Banco Le Danois.

In his work “Les Profondeurs de la Mer” (2), the prestigious French scientist describes this fishing ground, providing the first graphic sketch of its configuration. It is strange that this book, whose sub-title is “thirty years of research on the submarine fauna of the French coast”, give a description of the bottom of an area located within Spanish territorial waters, being barely 36 nautical miles away from the Ribadesella shore.

Could the news of its existence have reached him through his cooperation with Rafael de Buen Lozano (3), son of the founder of the IEO? Like his father and his brother Fernando, Rafael de Buen had a long scientific career, becoming a Professor at the Madrid Central University, which career was not interrupted when he went into exile in America, where he continued his research work. Both scientists -the Frenchman and the Spaniard- cooperated within the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), specifically, in the Atlantic Slope Committee, jointly publishing several reports (4).

Be that as it may, El Cachucho is the popular name under which the Banco Le Danois is known- due to the fact that its waters are rich in “cachucho” or red bream” (Berix splendens)- it being also the name currently chosen upon its designation as a Maritime Protected Area by Spanish law.

A mountain in the bosom of the sea

The fisheries bank known by the scientific world as “Banco Le Danois”, and popularly named El Cachucho, is a submarine mountain located approximately 36 nautical miles away from the Asturian shoreline, on the same latitude as the town of Ribadesella (5º West, with an elongated arrangement in East-West direction), in which an extraordinary maritime biodiversity has been discovered, consisting of more than six hundred recorded species, some of which were previously unknown to science.

In it, from North to South, four physiographical “provinces” can be distinguished: the shoulder, the internal basin, the Lastres canyon and the Cantabrian Sea continental shelf. The deepest point is located at the foot of the shoulder (over 4,000-metre deep). This first Spanish Maritime Protected Area has an extension of 234,966,8935 hectares. The geological origin of El Cachucho is related to compressive processes which took place during the Palaeogene (lower Tertiary) and brought about imbricate thrusts overlapping superimpositions which, in turn, resulted in an uplifting.

After the research carried out between 1934 and 1939 on board the oceanographic vessel “Presidente Theodore Tissier” by E. Le Danois, El Cachucho remained almost unexplored until 2003, in spite of laying very close to the shoreline and being the location of important fishing activities.

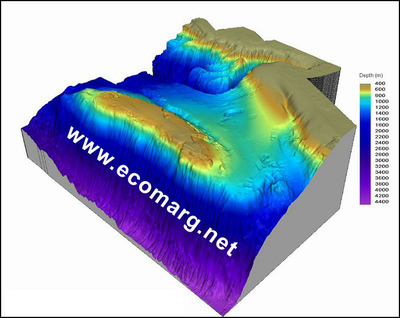

Digital map of the area. Source: IEO. ECOMARG

We are indebted to the research group known as ECOMARG (Continental Margin Ecosystems) for such knowledge of this area as we currently have. In addition to the Spanish Oceanographic Institute, the Ministry of the Environment is involved in this group’s activities. During the first stage thereof (2000-2005), the Higher Scientific Research Council (CSIC) and the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) also collaborated on the project; the latter, through the Arcachon Laboratory of Biological Oceanography. Nowadays a new research stage is underway which is due to be completed by the end of 2009.

This research project -or rather, set of multidisciplinary projects- is in keeping with the urgent need to know the structure and dynamics of marine ecosystems, an essential knowledge to the future management of their resources, if we wish to keep a balance between nature conservation and the yield of the fisheries according to the principles of sustainable development.

The general objective of the ECOMARG research group is the integrated study of the benthic-demersal ecosystem of the continental margin (shelf and slope) of the Cantabrian Sea and Galicia. It aims to know the structure, the constituent elements and the dynamics of the deep (between 100 and 1,000 metres) maritime ecosystem, where many human extractive activities take place. The project’s main research lines have been focused on the morpho-sedimentary study, on the dynamics of water masses, on the ecology of fishes and crustaceans, on the study of the fisheries operating in the area and on the ecosystem’s tropho-dynamic model. A sustainable use proposal has also been put forward.

The ECOMARG group has been using for its research the “Vizconde de Eza” oceanographic vessel. This oceanographic ship is deemed to be a large floating laboratory incorporating six specialized laboratories (chemistry, physics, acoustics, wet analysis and computing) equipped with an advanced set of scientific instruments. The boat -one of the most advanced in the world- is also capable of making bottom lifting at a depth of up to 5,000 metres. ECOMARG’s first campaign took place between October 6 and October 21, 2003.

Successive campaigns have witnessed the performance of advanced studies of the El Cachucho fishing ground, always laying emphasis on an integrated approach to them, in the hope that they may result in attaining the indispensable knowledge to the setting in operation of comprehensive management models, an essential tool for the achievement of sustainable development in the fishing grounds.

The person in charge of the campaigns already conducted and the one underway is Dr. Francisco Sánchez Delgado, from the Santander Oceanographic Institute (IEO). For information on the scientific aspects of this multidisciplinary research, the reader can consult the extensive literature concerning the matter at issue, being mostly the work of researchers attached to the IEO. http://www.ecomarg.net/publicaciones.html.

El Cachucho’s environmental values

Location of Essential Habitats (EFH)

As previously mentioned, the ECOMARG project does research into the Cantabrian Sea’s vulnerable maritime habitats, El Cachucho being numbered among them. Such habitats are of extraordinary importance either as refuges for endangered species, or for being essential to young or breeding specimens of fish populations being exploited in adjacent areas.

El Cachucho is a highly vulnerable ecosystem and a very important one to the breeding of commercially fished species such as blue whiting, white hake, monkfish and bluemouth. The most prominent biological communities are aggregations of deep-water sponges, cold-water coral reefs, groups of submarine mountains and sea-pens and burrowing megafauna communities.

In the area of El Cachucho at least three Essential Habitats (Essential Fish Habitat- EFH) have been identified. Such is the name of areas essential to the continued existence of the population of a certain species, for it is there that its members lay their eggs and carry out their recruitment; where their growth or any decisive stage of their biological development takes place.

In the 2004 campaign, gatherings of breeding adults were identified belonging to, at least, three fish species of commercial interest: blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou), white hake (Phycis blennoides) and deep water scorpionfish (Trachyscorpia cristulata). The breeders of these species are exceedingly scarce in the Galicia and Cantabrian Sea continental shelves, which indicates that these habitats found in El Cachucho are, probably, essential to their respective populations and very necessary for the sustainable development of the fishing carried out in areas adjacent to the continental shelf.

As regards threatened habitats, El Cachucho includes four out of the fourteen in the list of the OSPAR Convention. To be specific: i) Deep-sea sponge aggregations, ii) Cold-water coral reefs (Lophelia pertusa reefs) iii), Seamounts and iiii) Sea-pen and burrowing megafauna communities.

Over 600 catalogued species

The campaigns conducted by E. Le Danois already made it possible to draw a first sketch of El Cachucho’s faunistical wealth, as recorded in the bionomic profile used by this author to illustrate the aforementioned work, “Les profondeurs de la mer”.

The research campaigns carried out by the Spanish Oceanographic Institute, in collaboration with the General Secretariat of the Sea and other scientific institutions, have given details of the existence of a large wealth of species in the area, 612 having been identified to date, some of which were previously unknown to science. One of the reasons behind such wealth lies in the bank’s rocky structure which enables the settlement of organisms which are fixed to the bottom (corals, sponges, sea-whips, etc.), which, in turn, creates an habitat highly favourable to the establishment of a refuge for many other species.

In the Bank’s upper part, as well as in its internal basin, large-size sponge populations have been identified. By way of example, specimens have been found of the Geodia sponge weighing up to 15 kilograms, as well as large specimens of cup-shaped hexactinellid sponges (Asconema setubalense) more than 1-metre high. On the other hand, there is evidence of the presence of cold-water coral reefs in the Bank’s rocky areas and slopes. Large living specimens have been collected by fishing boats using drag-nets and gill-nets, although the great depth and the complex structure of the bottom inhabited by these corals, make it difficult to precisely locate them.

The existence of these habitats in El Cachucho is very important in view of the current concern for the attempted protection of the cold-water coral reefs found in certain deep areas in practically every sea, since they are highly vulnerable to certain fishing activities, such as the bottom trawl. Apart from that, these coral reefs are important carbon drains, for they accumulate it in their skeletons.

The main mechanism of El Cachucho’s high biological production lies in the input of organic matter particles coming from the water layers close to the surface (marine snow), which feed the forests of sea-whips whose polyps stretch out their tentacles to catch this nutritious “blizzard”. Other organisms are also very quick on the uptake of this snow, such as small swimming crustaceans (similar to the krill whales live on), which are extraordinarily abundant in the bank, constituting an important source of food for the rest of the species inhabiting it.

EL CACHUCHO’S GIANT SQUIDS

El Cachucho’s internal basin is one of the areas in the Planet where accidental catches of giant squids have most frequently happened. Species such as Architeuthis dux and Taningia danae (which can weigh as much as 900 kilograms and measure up to 14 metres) are relatively frequently caught in this area by ships using drag-nets. Giant squids find in the bank an appropriate environment to their existence, probably in the depths, although they are caught when they go up to the internal basin, about 800-metre deep, where they are within the reach of fishing boats.

Specimen of giant squid

Giant squid (Taningia danae) caught by Avilés fishermen in the El Cachucho’s internal basin. We can see the big photophores (the largest in the animal kingdom) that it carries in each arm, with which it can give out lemon-yellow sparkles. The tentacles are armed with two rows of strong hooks. This young specimen weighed 10 kilograms.

As previously mentioned, it is probable that this area’s habitats be essential to the populations of these species and, accordingly, most necessary to develop in a sustainable manner the fishing carried out in areas close to the Cantabrian Sea continental shelf. The breeders find refuge in El Cachucho, as well as large amounts of readily available food, lower fishing pressure and a current dynamics that makes it easier for their eggs and larvae to be carried to other areas favourable to their later development.

Presence of cetaceans in El Cachucho and adjoining areas

Cetaceans make up a group of mammals deemed to be species indicating the level of quality of the environment they inhabit. The attention they deserve from the media and from society at large, makes it feasible that the protection granted to these animals be concurrently extended to include the ecosystems being home to them. The presence of cetaceans in a given area has a special relevance to the designation of such area as a Spot of Interest to the Community (LIC) or a Maritime Protected Area (AMP).

The results achieved by the cetacean research project in the Asturian coastline (2004-2007) verify the significance of El Cachucho to a wide variety and a large number of cetacean species, the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops Truncatus) being one case in point, whose inclusion in Annex II of the Habitat Directive makes it a priority species, although it must be pointed out that all species of cetaceans are of interest to the community and demand strict protection according to the provisions of Annex IV of the said Directive.

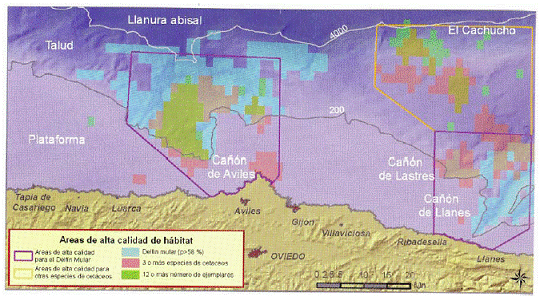

The map below shows the three high-quality habitat areas for cetaceans in the Asturian coast, El Cachucho being included in that number.

High-quality habitat areas for the bottle-nose dolphin and the rest of cetaceans in the coast of Asturias (Spain)

El Cachucho’s legal protection: an example of good governance

The biological richness of El Cachucho gave rise to its inclusion by WWF/Adena in the proposal publicly submitted by this NGO in Madrid on March 13, 2006, concerning its becoming a constituent element of a network of Maritime Protected Areas. A process was thus started which came to fruition when the Ministry of the Environment published a Ministerial Order whereby the appropriate measures were approved for the protection of this maritime area. (ARM/3840/2008 Order, approved on December 23)

Due to its natural wealth, El Cachucho’s maritime area meets the criteria, as laid down by Directive 43/92 EEC, approved on May 21, on the preservation of natural habitats and the wild fauna and flora, for it to be designated as a Spot of Interest to the Community within the Natura 2000 Network, doing likewise as regards the criteria to be included in the OSPAR Convention network of Maritime Protected Areas.

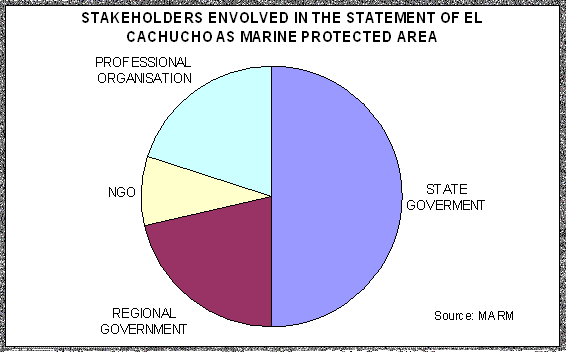

With a view to its being designated as a Maritime Protected Area, two working groups were established, one being scientific-technical in nature while the other dealt with legal-administrative issues, both of which were managed and coordinated by the Directorate-general for Biodiversity, dependent on the Ministry of the Environment. The groups endeavoured to carry out a dynamic and participatory process, finding room for all organizations that could contribute information and experience about El Cachucho, among which -in addition to the official and scientific bodies concerned- the Asturias Guilds of Fishermen and other associations belonging to the fishing industry, as well as to NGOs (WWF/Adena) and Oceana, were numbered.

The scientific working group did prepare a summary report on the Bank’s natural values, as well as the technical specifications for El Cachucho to be incorporated into the Natura 2000 Network and the OSPAR Convention network of Maritime Protected Areas. For its part, the legal-administrative working group did analyse the consequences of the designation of El Cachucho as a Maritime Protected Area and suggested the most appropriate procedure to the realization of such designation, by drawing-up a Draft Agreement to be submitted to Cabinet.

Right in the middle of the discussion process, Act 42/2007 on Natural Heritage and Biodiversity was promulgated on December 13, which enabled the placement of the initiative within an adequate national legal framework. The said Act creates the concept of Maritime Protected Area, defined as “those natural areas selected for the protection of ecosystems, communities or biological or geological elements being constituent of the maritime environment, including the intertidal and subtidal areas, which because of their rarity, fragility, importance or uniqueness deserve special protection”.

The next step was the approval by the Cabinet of an Agreement (dated March 12, 2008) whereby a series of measures were taken aimed at the maritime protection of El Cachucho, and coordinating the fields of responsibility of each ministerial department so that they be efficiently exerted.

The preventive protection regime for this maritime area was focused on the implementation of three main measures: the refusal of any hydrocarbon prospecting permission, the prohibition of any kind of extraction activities and the prohibition of military manoeuvres entailing underwater explosions or the use of low-frequency sonar. It is worth mentioning that the Agreement was reached at the suggestion of seven ministries, which proves the high level of consensus achieved on the protection of the bank.

In the ARM/3840/2008 Ministerial Order, in addition to the designation process of El Cachucho as a Maritime Protected Area, it is also stipulated that the procedure be started for the approval of the Natural Resources Regulation Plan, as well as the area’s inclusion in the list of Spots of Interest to the Community (LIC) and in the OSPAR Convention network of Maritime Protected Areas (AMP), one of whose priorities is the protection of the maritime environment of the North-eastern Atlantic area by means of the establishment of a Network of Maritime Protected Areas in non-coastal maritime areas meeting certain environmental requirements.

To that end, the Member Estates suggest areas of interest within their respective territorial waters, including the Exclusive Economic Zone. Nowadays, the Network has 82 areas in the territorial waters of six Estates, Spain having incorporated into the network in 2007 the Islas Atlánticas de Galicia National Park. El Cachucho has been recently included, once its integration as a Marine Protected Area was approved by the OSPAR Commission in June 2009.

Traditional non-industrial fishing as against the use of the rock hopper

From the point of view of the exploitation of fishing resources, the fishing ground is used by a small number of boats, the majority of which operate from Asturian ports, fishing for Norway lobster, monk fish, white hake and other species of commercial value.

Red seabream and deep-water sharks were once fished in the area, although that sort of fishery is currently deemed to be exhausted. Traditional non-industrial fishing -adapted to the species’ cycles and using limited resources- has been respectful of the ecosystems. In this regard, the defence is worth mentioning made by the Cudillero, Luarca and Bustio, Asturias, guilds of fishermen, of these traditional nets during the process leading to the designation of El Cachucho as a Maritime Protected Area. However, the introduction of more aggressive techniques -such as the rock hopper- is at the root of the serious damages sustained by maritime ecosystems.

The campaign launched by the ECOMARG group in 2005 was called “TREBOL” (survey of the impact made by the “tren de bolos” [Spanish for Rock Hopper]) and it was conducted for the purposes of honouring the commitment made by the then called General Secretariat of Maritime Fisheries, dependent on the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA) and by the Government of the Principality of Asturias, in view of the requests made by the fishing industry, that wished to know the repercussions that this kind of fishing could be having on the bottom’s ecosystem and its resources.

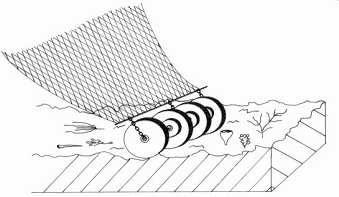

Sketch of the groundrope of a drag-net equipped with rock hopper used in the Cantabrian Sea.

Source: IEO. ECOMARG

The rock hopper is a fishing technique -authorized by the European Union but forbidden in Spain for the last twelve years (5/12/1995 Order)- preventing the net from getting caught on the rocky bottoms, which has been used over the last few years in the Galician National Bank and in the Cantabrian Sea. Due to the catches it can make, the drag-net with rock hopper is in direct competition with traditional coastal-fishing nets, creating a deep sense of unease in the non-industrial fishing sector, which has witnessed how one of its unique exclusive areas has ceased to be so. In addition, the habitat of its target species is likely to be altered by this kind of fishing technique.

Apart from possible direct damages suffered by the bottom and by the uncaught species -not to mention the butchery inflicted on commercial species-, other effect caused by the drag-nets is the havoc played with the species void of commercial value, which are usually thrown away once on board. Discarded species account for an important percentage of the catch: up to 35% of the whole thereof. Discarded fishes may or may nor survive depending on several factors, such as how long is the drag-net in the water, the catch’s total volume, how much time do the animals stay on deck, the wounds or the knocks suffered, etc.

Catches made with the rock hopper at El Cachucho: among other species, sponges

(Geodia megastrella) and sea whips (Callogorgia verticillata) can be seen. Source: IEO. ECOMARG

Generally speaking, the repercussions that drag-nets have on epibenthic species are the modification of the substratum (turned over, broken or displaced rocks, sediment transport and deposit…), the elimination of biogenic materials and the resulting decline of the associated fauna. During the campaign, the short-term repercussions of the rock hopper on the affected communities were studied, but no data are available concerning the medium and long-term effects.

Having said that, it must be pointed out that the most serious and lasting consequences are those which will come about in the long term, numerous authors having drawn attention to the damages already being sustained by deep reef areas. In this regard, it must be mentioned that, after three campaigns in El Cachucho, no living coral reefs have been found (Lophelia pertusa is the reference species and nothing but their dead skeletons ever appeared) although they were alluded to in historical works (Le Danois, 1948) and there is a specimen in the Cantabrian Maritime Museum caught by a trawler which used to operate in the area.

This fact alone could make up the evidence of the accumulated historical impact made by trawling and gill-netting activities on the area, just as it happened in similar areas (Rockall or Porcupine Banks) whose coral colonies have been damaged or have disappeared as a result of the trawl, due to physical damage or to their being buried under sediments.

Towards the establishment of the Natura 2000 Network in Spanish maritime waters

The “Biodiversidad Foundation”, dependent on the Ministry of the Environment, did submit to the European Commission a project whose purpose it was to incorporate into the Natura 2000 Network several Spanish maritime areas. That project was selected to be financed with funds from Life+. The project has been named INDEMARES (Inventory and designation of the Natura 2000 Network in Spanish maritime areas).

This particular nature preservation project has one of the biggest budgets (15.4 M €), half of which is to be provided by the European Commission. The project partners, namely, the Biodiversidad Foundation, the Ministry of the Environment (through the General Secretariat of the Sea), the Spanish Oceanographic Institute (IEO), the Higher Scientific Research Council (CSIC), the Coordinating Committee for the Study of Sea Mammals, OCEANA, the Society for the Study of Cetaceans in the Canarian Archipelago (SECAC), the Spanish Ornithological Society - SEO/BirdLife and WWF España, will defray the rest of the expenses. The Ministries of Defence, Public Works and Foreign Affairs will also provide support.

Work has started in January 2009 and is scheduled to last five years, until December 2013. The general objective is gathering enough scientific information for the preservation of wide areas of the Spanish maritime environment through the designation of Spots of Interest to the Community (LIC) and Special Zones for the Protection of Birds (ZEPA).

The project’s specific objectives are focused on submitting to the European Commission for approval a list of spots that should become a part of the Maritime Natura 2000 Network; encouraging the participation by all concerned parties in the research, preservation and management of maritime resources; having management guidelines for the proposed areas and contributing to the strengthening of Maritime International Conventions signed by Spain (OSPAR and Barcelona).

To achieve the aforesaid objectives, a series of actions have been envisaged including the location and preliminary assessment of places of interest, the performance of scientific studies and oceanographic campaigns, the monitoring of human activities, assessing the fisheries’ impact on the LIC and the ZEPA included in the proposal, and the overseeing and assessment of deliberate pollution through the spillage of hydrocarbons within the sphere of the Natura 2000 Network.

These scientific activities will be backed up by means of information and awareness campaigns aimed at a wider public; among them, user-oriented information seminars to be held in each of the ten coastal Self-governing Regions.

The areas being the subject matter of the study which are likely to be a part of the Maritime Natura 2000 Network, are located in the Atlantic, Mediterranean and Macaronesian regions and are the following ones: Creus Canyon, Ebro Delta- Columbretes Islands, Menoría Channel, Seco de los Olivos, Alborán Island and volcanic cones of Alborán, Cadiz Chimneys, Galician Bank, Avilés Canyon, La Concepción Bank and Gran Canaria-Fuerteventura Area.

INDEMARES project: study areas. Source: Biodiversidad Foundation

The preservation of the marine environment by successfully combining the former with the latter’s economic exploitation is the main objective of Directive 2008/56/EC of the European Parliament and the Council, approved on June 17 2008 and currently in the process of being incorporated into Spanish National Legislation. Previously, by means of the “Habitat Directive” and the “Bird Directive”, important steps had already been taken towards the preservation of biodiversity and the honouring of the commitments made in favour of sustainable development. With these instruments, the time seems to have come to successfully combine the exploitation or maritime resources with the scientific knowledge thereof and the preservation of their biological diversity.

The launching of ambitious and motivating projects, such as INDEMARES, for the Spanish scientific world, the establishment of protected areas in our seas and the creation of networks being representative of their ecosystems will all undoubtedly contribute to the preservation of maritime resources.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning that El Cachucho has become a Spanish paradigm of the steps to be taken to achieve comprehensive protection for a maritime area having all the features of a “biological diversity hot spot” in the Cantabrian Sea, being also an archetype of the commitment made by the Ministry of the Environment to achieve that goal.

Main Sources:

- Fundación Biodiversidad: Proyecto INDEMARES. LIFE+ 07/NATE/E/000732 “Inventario y designación de la Red Natura 2000 en áreas marinas del Estado español” http://www.fundacion-biodiversidad.es/es/medio-marino

- Heredia Armada, B; Pantoja Trigueros, J; Tejedor Arceredillo; Sánchez Delgado, Francisco: “La primera gran área marina protegida en España: El Cachucho, un oasis de vida en el Cantábrico”, in Ambienta, April 2008, p. 10-17 http://www.mma.es/secciones/biblioteca_publicacion/publicaciones/revista_ambienta/n76/pdf/10cachucho762008.pdf

- Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO): “Proyecto ECOMARG: Estudio del ecosistema de la plataforma marginal asturiana e impacto en sus pesquerías”, in Hoja Informativa, nº 91, February 2005 www.ieo.es/images/pdfs/febrero_2005.pdf

- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, y Medio Rural y Marino (MARM): “Informe de síntesis de los valores ambientales de El Cachucho”. September 12, 2008 [document published in the MARM website http://www.mma.es/secciones/acm/aguas_marinas_litoral/prot_medio_marino/biodiversidad/pdf/bm_ep_informe_sintesis_cachucho.pdf

- Instituto Español de Oceanografía (IEO): “Campaña TREBOL 2005: Estudio del impacto del tren de bolos/ Realizado por el Grupo de Investigación ECOMARG, 23 p.”www.ieo.es/apartar/varios/trebol_2005.pdf

- OSPAR COMMISSION: “Hello El Cachucho” (Press release) [October 24, 2008]; 3 p. http://www.ospar.org/content/news_detail.asp?menu=00600725000000_000005_000000

- WWWF/ADENA: “Conservando nuestros paraísos marinos: propuesta de Red Representativa de Áreas Marinas Protegidas de España”. September, 2005 [Digital Edition] Publicly presented on March 13, 2006. http://assets.wwfes.panda.org/downloads/conservando_nuestros_paraisos_marinos___peninsula_iberica_y_baleares1.pdf

1) In biogeographical terms, the El Cachucho maritime area is to be placed within the Lusitanian Province and, more specifically, in the warm sub-province (code 15, Warm Lusitanean subprovinciae). According to the OSPAR Convention classification, it is within Region IV (Bay of Biscay/Gulf of Gascony and Iberian coast).

2) Le Danois, Edouard: Les profondeurs de la mer: trente ans de recherche sur la faune sous-marine au large des côtes de France. Paris: Payot, 194

) Rafael de Buen Lozano (1891-196?) was the author of the first “Treatise on Oceanography” published in Spain (IEO, 1924). He devoted a large part of his efforts to the study of the bottom of the sea; among its earliest bibliography, the following works can be mentioned: “Estudios de fondos marinos”, in the Boletín de la Sociedad Oceanográfica de Guipúzcoa, Revista de Estudios Científicos del Cantábrico y de Ictiología Marina y Fluvial, vol. IV, núm. 17 (1916) pp 188-197. “La vida en las grandes profundidades del mar” in Boletín de Pescas, vol. VI, núm. 56-58 (1921) pp. 158-175. “La primera carta de pesca española” [concerning the Basque Country coast], in Boletín de Pescas, vol. XI, núm, 122 (1926), pp. 81-84.: “Cartas en relieve del fondo del mar” in Boletín de Pescas, vol. XII, núm 126 (1927), pp. 35-37.7

4) Le Danois, Edouard; De Buen, Rafael: Rapport Atlantique 1927: travaux du Comité du plateau continental (Atlantique Slope Commitee). Copenhague: And. Fred. Host & Fils, 1929

Document Actions

Share with others