The state of the ocean environment is a matter of fundamental importance for Iceland. The core objective of the country’s policy on marine issues is to maintain a healthy ocean environment and to ensure sustainable utilisation, so that the ocean can continue to serve as a bountiful source of both healthy and valuable products and remain one of the mainstays of the country’s economy as well as all other ecosystem services.

Around 270 species of fish have been found in Icelandic waters and some 150 species are

known to spawn there. The majority of fish species in Icelandic waters are demersal species,

while there are relatively few pelagic species. Almost 2000 species of benthic fauna are identified. Two seal species, the harbour seal and grey seal, give birth to their offspring here. At least seven species of toothed whales and five species of baleen whales are common in Icelandic waters.

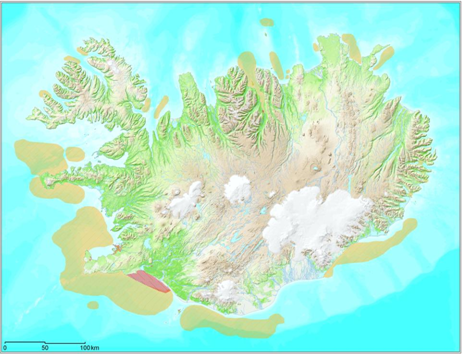

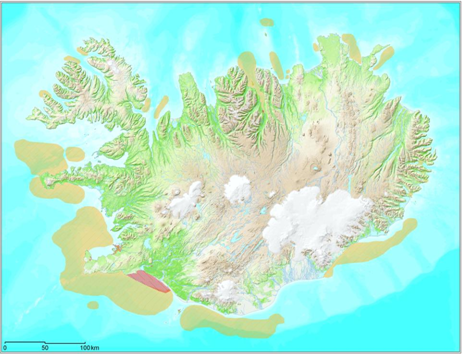

Figure 1. The main spawning grounds for cod around Iceland

Sea birds are important parts of the coastal and marine ecosystems in Iceland. The number of nesting species is low, but the populations can be very large for some species of seabirds, wading birds and waterfowls.

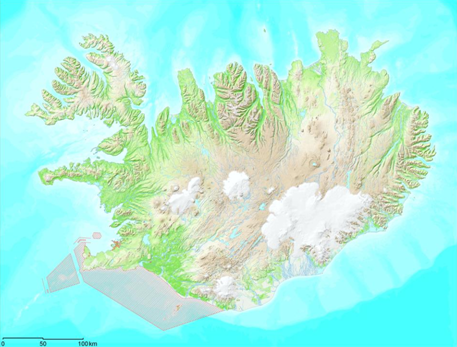

Figure 2. The main seabird colonies in Iceland

Iceland is an important breeding ground world wide for some birds such as razorbilled auk and puffin. Iceland is also an important stop-over in the route of some migrating birds such as geese and wading birds between the nesting sites in Greenland and Canada and the overwintering sites in Europe.

There has been very little utilisation of the ocean area around Iceland and its resources, with the exception of fishing banks. Sea-bed extraction has been very limited and the conditions for petroleum extraction are still under exploration. The ocean has always been used for travel and transport. The ocean, its coastline and marine life attract both Icelandic and foreign travellers and development of services linked to nature excursions has been increasing. Changes in marine and coastal zone utilisation makes it neccesary to set up strategies and implement management and protection schemes (action programmes) to ensure long-term maintenance of sustainable ecosystem services, ecosystems and populations.

Icelandic waters receive environmental contaminants such as persistent organohalogens and heavy metals from far outside the region, and marine fauna is exposed to these long-range transported contaminants (1). However, levels of persistent organic contaminants are relatively low and the concentration of pollutants in marine products from Icelandic waters is generally well below critical limits. Trends in PCBs concentrations appear to be decreasing (1), most likely because of more strict international regulations on emission of pollutants. Iceland is a remote and sparsely populated country and the general environmental conditions are good. Iceland is within the cleanest regions (Region I) in the OSPAR Convention area and a non-problem area with regard to nutrient enrichment. Higher concentrations may be found close to the most populated areas in Iceland although they are still low compared to those in urbanised areas (1, 2). There are also some exceptions in concentration of organohalogens depending on differences in trophic level and metabolic capacity that indicate impacts on bird fauna (3). Thus, emerging componds are a growing concern in the northern hemisphere. There were also a major concern regarding the effects of tributyltin (from TBT-based antifouling paints) in the marine environment early in the last decade and imposex levels in dogwhelk are monitored regularly in Iceland. Although the imposex levels still remain high near the large harbour complexes in the capital area, it is evident that regulations, including the use of less toxic antifouling paints and community action, have led to substantial improvements of the imposex levels in dogwhelk in the monitored harbors (4).

Oil spills and accidents are other priority issues of concern with regard to the potential impacts on marine and coastal resources. The main sources of oil from land are wastewater from urban areas and industry, evaporation as well as involuntary releases and accidents. Oil pollution is probably mainly due to minor accidents. The large risk factors are accidents from large supply depots, shipping and transport. Potentially, a large impact may occur if there is an overlap in time and space between an accidental oil spill and migratory animals such as seabirds, which congregrate within relatively small areas at certain times (5).

Recent international developments have increased international vessel traffic, including oil transport, in Icelandic waters. Earlier mostly vessels with products for the Icelandic marked were found on this route. Each year some 700 000-800 ,000 tonnes of petroleum and petroleum products are transported to Iceland. By far the greatest portion of this transport goes through harbours in the southwestern Faxaflói bay area via sailing routes along the country’s south coast. Oil is distributed by coastal shipping (and land transport) from the Faxaflói area to other parts of the country.

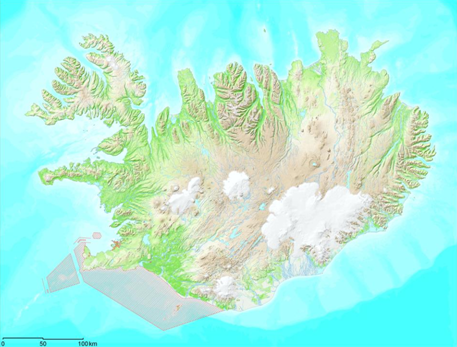

Figure 3. The main sailing routes around Iceland

Nowadays large oil vessels sail within Icelandic jurisdiction on the way from the White Sea in northeast Russia, westward to North America. Oil leaking into the ocean near important spawning grounds, rich fishing banks or bird colonies as a result of an accident could have catastrophic effects on ecosystems and might spread fast clockwise by coastal currents along the country’s coast (6).

Ocean transport is of major and far-reaching significance for Iceland. The nation has traditionally been and will continue to be highly dependent on ocean transport of products to and from the country. Vessel traffic thus provides the basis for communication and trade with other states. It is possible that climate change in the Arctic may result in shipping routes opening up through Arctic regions, linking the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. This might result in greatly increased traffic through Icelandic waters. The number of cruise ships visiting Iceland has increased greatly in recent years. For 15-20 years, the number of cruise ships was around 20 each year with 8 000 to 12 000 passengers, but in 2008 the number of vessels visiting Reykjavík was 83, with just under 60 000 guests (6, 7). The outlook is that within few years almost 50 million tonnes of crude oil will be transported annually through Icelandic waters. The main routes within the Icelandic jurisdiction are either east and south of Iceland or north and west of the country (6).

The Ministry for the Environment has developed an action programme for the prevention of land‑based marine pollution. The plan is based in the Global Programme of Action on the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Sources of Marine Pollution (GPA) adopted in Washington in 1995 (5).

In the National Action Plan further steps are recommended for measures to prevent ocean pollution from land-based sources, for instance, by classifying coastal areas according to the factors that primarily determine the local impact of sewage disposal, mapping the emissions of POPs and heavy metals from wastewater outlets, mapping polluted spots and compiling an evaluation of the concentration of nutrients near large aquaculture installations. In order to evaluate the potential threats and impacts and to build a platform for responses, mapping of habitats close to land, creation of risk maps with regard to oil pollution of coastline and creation of reaction plans for serious pollution accidents are being implemented.

To increase knowledge, more research was recommended on the possible impact of pollution and other environmental changes, together with monitoring of such changes in the ocean ecosystem and their economic and social consequences. Public institutions involved in research and monitoring of the oceans should coordinate their activities as much as possible, and work jointly on data and information collection. In addition, it is important that consultation and cooperation be increased in presenting information on monitoring and the results of scientific research (5).

The Ministry is implementing the action programme in several steps (5):

- Guidelines have been published for the authorities on how to respond to pollution accidents. The report includes a great deal of information expected to be useful in risk analysis and compilation of response plans, to enable a more effective response to pollution accidents at sea.

- A web‑based information system is under preparation in cooperation with other nordic countries in the North Atlantic. The system covers:

Nature – sensitive and important areas, nature reserves, wildlife biology, weather etc.

Risk factors – possible pollutants, marine traffic, offshore activities, shipwrecks, drainage etc.

Response – who can respond and how, locate rescue and response teams and equipment.

Iceland is a party to numerous other agreements concerning the protection of the oceans. These include, for example, IMO agreements intended to reduce pollution from vessels and prevent discharges of wastes and pollutants, and the OSPAR convention which lays down rules and guidelines that aim at minimising the impact of activities on land and of offshore installations on the marine environment. Furthermore, there are several agreements concerning oil pollution and equipment and response capacity, providing for international collaboration in cases of accidents.

Accidents involving vessels at sea can result in a danger of pollution. According to Icelandic laws and regluations, ships carrying oil and other hazardous substances are required to notify the Icelandic Maritime Administration before entering the Icelandic EEZ and report their sailing routes through the area. Furthermore, areas off the southern and southwestern coast of Iceland have been declared as Areas to be Avoided (Figure 4.) in order to enhance safety of sailing and increase response possibilities in case of incidents at sea.

Figure 4. Areas to be avoided and with restriction (regulation) in sailing off the Icelandic coast.

References

(1) Quality Status Report 2000. Region I – Arctic Waters. http://www.ospar.org/content/content.asp?menu=00790830300000_000000_000000

(2) State of the Environment. Report in Icelandic. http://www.umhverfisraduneyti.is/media/PDF_skrar/umhverfiogaudlindir2009.pdf

(3) Hrönn Jörundsdóttir, 2009. Temporal and spatial trends of organohalogens in guillemot (Uria aalge) from North Western Europe. Department of Environmental Chemistry. Stockholm University. Doctoral Thesis 2009. ISBN 978-91-7155-736-0. US-AB, 2009.

(4) Katla Jörundsdóttir, Jörundur Svavarsson og Kenneth M.Y. Leung 2005. Imposex levels in the dogwhelk Nucella lapillus (L.) – continuing improvement at high latitudes. Marine Pollution Bulletin 51: 744-749.

(5) Iceland´s National Programme of Action for the protection of the marine environment from land-based activities. Report in English. http://eng.umhverfisraduneyti.is/media/PDF_skrar/GPA.pdf

(6) Report with proposals to enhance safety of sailing. Report in Icelandic. http://sigling.is/lisalib/getfile.aspx?itemid=3365

(7) Tourism in Iceland in figures, oct 2010. Report in English. http://www.ferdamalastofa.is/upload/files/Tourism_in_Iceland_in_figures_oct_%202009.pdf

Document Actions

Share with others