The various characteristics

described in the ‘Societal developments’ chapter play a crucial role in the

state of the environment and present many challenges for environmental and

sustainable development policies.

First of all, the dimension

of the country, as well as the size and the structure of its economy, explain

why, for example, an industrial project may have a significant impact on the

environment [Note 5] or why the use of fiscal

instruments to influence behaviour could be limited [Note

6]. Small size also implies that environmental concerns quickly become

transboundary issues.

Both the strong population

growth as well as the even stronger cross-border commuter growth have led to

increasing built-up areas (housing, offices, services, infrastructures) and to

ever growing transport flows, mainly by road. Population growth, coupled with

the economic development in the tertiary sector, is a key driver of urban

sprawling and land fragmentation (Luxembourg is the second-most

fragmented country within the EU). Various actions and land planning are

undertaken by the authorities to limit urban sprawl. However, the demographic

pressure is leading to very high prices for construction (houses, apartments,

land) that, in turn, generate social problems such as access to accommodation

and the ability to pay. Consequently, there is also a wish for more building land

in order to reduce prices.

Population and cross-border

growth are also leading to rising energy demand, both for buildings and for

transport. Concerning the latter, although Luxembourg invests predominantly

and jointly with the neighbouring regions in public transport in order to alter

the current modal split of home-work journeys, a vast majority of workers from

abroad commute by car (90 % of these journeys according to a study

performed in 2007).

The fact that cross-border

commuters now represent 30 % of the resident population is generating

concerns in both the waste and wastewater sectors (oversize investments with

regard to population, high per capita ratios that do not necessarily reflect

the average actual use by the resident population).

Finally,

one of the biggest challenges for Luxembourg is related to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets. At

present, Luxembourg does not have the significant technical potential which exists in

other countries where residual ‘old-technology’ industrial and power plants

still operate. In Luxembourg, there has been, and there still is almost no reduction potential of

GHG emissions stemming from the modernisation or the replacement of existing

national industrial or power plants. In fact, with the move from blast to

electric arc furnaces in the steel sector during the 1990s, Luxembourg very soon exhausted its only major technical potential for GHG

emissions reduction. Therefore, the EU ‘Climate and Energy Package’ adopted in

2008, which intends to contribute to a common energy policy and to combat

climate change after 2012, will be highly challenging for Luxembourg since it

calls the country: (i) to reduce GHG emissions by 20 % below their 2005

level for sectors outside EU-ETS; (ii) to achieve an 11 % share of

renewable energy in total energy consumption by 2020; and (iii) to achieve a 10 %

share of biofuels in total transport by 2020.

However, the promotion of

renewable energies in the electricity sector, which is associated with major

investments and subsidies, is of little interest with regard to Luxembourg’s GHG balance.

Indeed, additional capacities based upon renewable energies cannot actually be

used to replace any electricity from inefficient existing fossil-fuel plants in

Luxembourg. Nor will they

substitute the highly efficient national production plants which have recently been

constructed. In reality, they will replace imported electricity which does not

appear in Luxembourg’s GHG balance

according to the IPCC accounting rules.

These accounting rules also

require the very high ‘road fuel sales to non-residents’ – almost 75 % of the total road fuel sales due to lower fuel prices in Luxembourg than in the neighbouring countries – to appear in its GHG balance. Luxembourg's location at

the heart of the main traffic axes for western Europe and its economic

development have made it a focal point for international road traffic. Therefore,

Luxembourg has traditionally

had a high volume of road transit traffic for both goods (freight transport)

and passengers (tourists on their way to or back from southern Europe). The latter

has increased even further due to the high number of commuter journeys observed

every working day. In comparison with international traffic, domestic traffic

plays a relatively small role since it is responsible for only one-quarter of

the total road fuels sold in Luxembourg. As a consequence,

in 2009 ‘road fuel sales to non residents’ (transit traffic, commuters and ‘fuel

tourism’) represented 38 % of the total GHG emissions [Note 7].

Though price differences with

neighbouring countries is reducing over time (notably, through increases in

excises), and though Luxembourg committed itself to respect both its Kyoto

target (a reduction of 28 % compared to 1990) and the 20 % cutback decided

in the framework of the EU ‘Climate and Energy Package’, it cannot be expected

that these price differentials will be entirely offset in the coming years.

Indeed, that would require aligning prices to those of the most expensive

bordering country with a risk of reverse ‘fuel tourism’ due to the size of Luxembourg. Moreover, such

a policy will not lead to any substantial reduction of GHG emissions at the

European level since ‘fuel tourism’ related emissions are the smallest part of ‘road

fuel sales to non-residents’. Hence, emissions will only be transferred from Luxembourg’s balance to

those of its neighbours.

For more information on the

GHG and energy challenges, see climate change and mitigation common

environmental theme.

All these challenges are

well and carefully considered by the authorities through a set of plans such as

a cross-sector integrated plan (IVL – ‘Integratives Verkehrs- und

Landesentwicklungskonzept für Luxemburg’), various

sectoral Action Plans [Note 8] – some of them

deriving from the cross-sector integrated plan – as well as Action Plans aiming

at fulfilling the objective set to Luxembourg by the EU ‘Climate and Energy Package’,

i.e. the Renewable Energy Action Plan – that has been

adopted by the Government end July 2010 – and the revised national CO2

reduction Action Plan due by 2011. Together

with the second National Sustainable Development Plan expected by end

2010, the CO2 reduction Action Plan will be the result of an

extensive consultation of stakeholders in the framework of the ‘Partenariat

pour l’Environnement et le Climat’ put into place

by the present Government – for details, see one of our national and regional

stories.

Conclusion: overview of the national circumstances

Key points that play a role

in environment issues and policies in Luxembourg in the past and

the future are:

- a country characterised by both

high demographic

and high economic

growth in a stagnating region, hence an attractive economic

destination;

- strong population growth

due to immigration that is expected to continue;

- even stronger cross-border commuter growth that is also expected continue once the financial and economic

crisis is over;

- increase of built-up areas

(housing, offices, services, infrastructures) as a consequence of the previous

statements;

- location at the heart of the

main western European transit

routes for both goods and passengers;

- increase of transport flows as a consequence of the previous statements;

- small size and open economy: a new industrial project, a technological

change, a closure or a breakdown of a production unit might have significant

impacts on the GHG and air pollutants emissions and increase the overall

uncertainty of emissions projections;

- limitations in taxation policies due to short distances to

neighbouring countries;

- a country that needs to cooperate and to

interact with its neighbours since environmental issues quickly become

cross-border issues;

- limited national GHG and

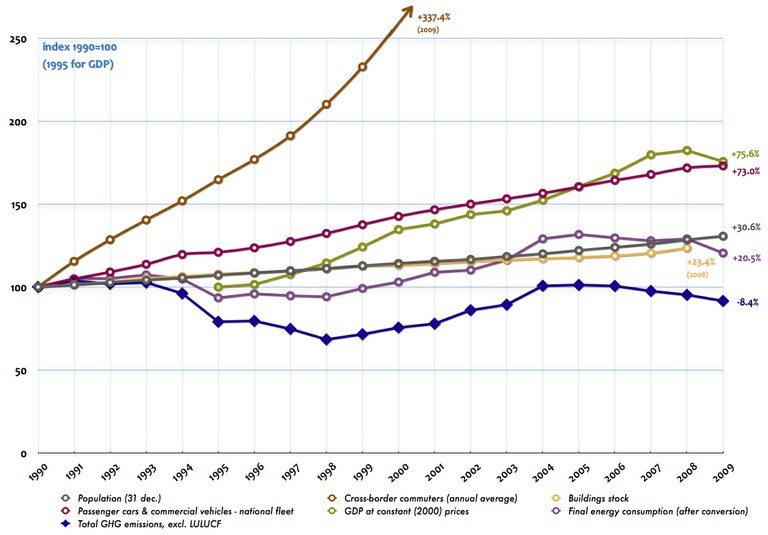

air pollutants emissions reduction potential. [Figure 4]

Figure 4 - Key variables trends: 1990-2009

Sources: STATEC, Statistical Yearbook and Ministry of Sustainable Development and Infrastructure - Department of the Environment.

Notes:

a) building stocks: estimates calculated by the Department of the Environment;

b) GHG emissions and final energy consumption: 2009 data are provisional.

Notes

[1]

Data prior to

1995 have not been converted into the latest system of national accounts to be

used at EU level (ESA 95). Hence, the developments could only be calculated

from 1995 onwards.

[2]

Percentages

would have been 82.3 % and 4.7 % respectively if the calculations

were made on the year 2008 rather than 2009: with the financial crisis and the

economic downturn that follows, Luxembourg’s economy decreased by 3.7 %

between 2008 and 2009 (in 2008, the GDP at constant price – the highest ever

recorded – was 1.4 % higher than in 2007. Hence, the crisis is only

perceptible in the 2009 results).

[3]

Luxembourg’s

enterprises being not able to locally find high profile applicants for the

positions they are offering, they attracted non-residents. Hence, in the years

2000s, Luxembourg

experienced increasing higher unemployment rates whilst new job creations have

never been so high.

[4]

Since 1960, the

growth is 59.4 % !

[5]

For instance, in

2002 the construction of a gas and steam power station led to an increase in Luxembourg’s

greenhouse gas emissions of 0.9 to 1 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent per year,

i.e. around 8 % of the total greenhouse gas emissions attributed to Luxembourg.

Another example is provided by the flat glass industry in Luxembourg (two

plants): it is the major culprit for NOx emissions outside the road

transportation sector.

[6]

Most of the

resident population has only to drive 30 km or less to be abroad.

Consequently, increasing taxes or excises on some products (e.g. road fuels)

will have effects on the whole country and not only at the borders as it is the

case in bigger countries. Fiscal incentives could also attract non-resident to Luxembourg.

Consequently, tax and subsidies policies are mainly directed towards sectors

and activities that are not subject to transboundary effects: e.g. incentives

for energy-efficiency and the use or renewable energy sources in the building

sector.

[7]

The highest

percentage ever recorded was 41.3 % in 2005. See also the ‘State and

Impacts’ chapter in the climate change and mitigation common environmental

theme.

[8]

Plans or

programmes such as ‘transports’,

‘landscape’,

‘rural development’,

etc.

Other interesting links

Statistical yearbook: click here (in French) and here (in French).

Luxembourg in Figures: click

here (in French, German and English).

The Luxembourg economy. A

kaleidoscope 2008: click here (in French and English)

Second, Third, Fourth and

Fifth National Communication of Luxembourg under the

UNFCCC – Chapter II: click

here.

Luxembourg’s National

Inventory Report 1990-2008 – Section 2.1: click here.

Document Actions

Share with others